From New York to Vermont: Conversation with Steve Reich

Rebecca Y. Kim

Taking a break from his latest project, Three Tales, Steve Reich discusses the techniques, influences, and implications of some of his past works, starting with Music for 18 Musicians. The interviews took place at his New York City apartment on October 12, 2000 and by telephone to his Vermont home on October 25, 2000.

Music for 18 Musicians (1974-76)

What kinds of things were you thinking about when composing Music for 18 Musicians?

Well, harmony and orchestration were very high on the list. Rather than starting with a melodic cell, which had been the starting point for Piano Phase, Violin Phase, Drumming, and basically all the pieces preceding Music for 18 except for Four Organs, the way I composed Music for 18 was by starting with a series of chords. The idea was to extend the middle register, not the bass—remember the Debussy flute melody beginning Afternoon of a Faun and that same melody repeated with different bass notes. In other words, key signature is structure and bass is color. You’re in three sharps which can mean A major, F# minor, B dorian and so on.

Works like Six Pianos, Four Organs, Violin Phase, and Piano Phase had been dealing primarily with multiples of instruments of the same timbre, and this was done both as an aesthetic choice and an acoustical necessity. It was necessary to have instruments of the same timbre playing against one another so that all the sub-patterns would emerge clearly. When you have six pianos, after a while you don’t know who’s playing what; all you know is that all this is happening, and you begin hearing all kinds of sub-patterns because everything blends together. If you were to play Piano Phase on harpsichord and piano, this wouldn’t happen. You could do it on two harpsichords and on two synthesizers of the same timbre, but you just have to match them.

With Music for 18, I began to think, “Well, there’s an awful lot of music for dissimilar instruments.” Therefore, Music for 18 Musicians was, in a sense, a riot of color compared to what came before it. Music for Mallet Instruments, Voices and Organ is the parent and is certainly lurking there in the background; that’s where beautiful sound became a major consideration, as well as mixing timbres, and mixing very long held tones with very short eighth notes started. But, Music for 18 takes the harmonic aspect of that piece and expands it into completely new territory.

You added more color toward the end of Drumming.

There is a kind of continuity between Drumming Part IV, Music for Mallet Instruments, and Music for 18, but Music for 18, as a lot of people have noticed, combines the old and the new. While there is a new intense interest in harmonic variation, changing key, changing mode particularly, and in changing orchestration, there is also the xylophone being built up against the other xylophone and the high pianos are paired with each. Hence, that old pairing is there, and of course it’s still there today, but the idea of pairing instruments against one another to produce canonic sub-patterns is now part of rather than all of the piece; Nagoya Marimbas is an exception because it is basically doing an old piece more recently. Music for 18 Musicians was a step, if you like, backwards, backwards into the Western tradition, into harmonic variation, into orchestral color, and [laughing] in a sense I never stopped moving backwards until Different Trains in 1988.

This step “backwards” into Western tradition seems to have been a big step forward for you stylistically.

It essentially was. There are artists in the visual arts who more or less do the same things their whole lives. A certain minimal artist, whom I won’t name, made boxes—steel boxes, blue boxes, wood boxes—and that was his life. Then there are artists like Frank Stella; he made black and white grid paintings, dayglo color grids, then the grids became chicken wire, which got bent out of shape off the wall, and pretty soon he was doing sculptures. Therefore, when someone asks, “What’s the next Frank Stella show going to be?” You answer, “Well, let’s see what he does.”

I turn out to be that kind of artist, because that’s who I am. I got bored writing phase pieces. I couldn’t write any phase music after 1971. I couldn’t write Music for 18 Musicians or anything like that now. I just move on to the next thing that seems to need doing.

So, with Music for 18 you moved on from what’s been identified as your early “minimalist” style?

Well, yes. There is an interview that was done with Michael Nyman shortly after the piece was completed. In it, he asked whether I was interested in doing minimal music, and I said, “No, I’m not.” I’m interested in doing what genuinely interests me and that keep changing . I was recently at Dartmouth as a Montgomery Fellow earlier in the spring, and an undergraduate in one of the classes had apparently just read my 1968 essay, “Music as a Gradual Process.” After I played a piece from last year, Triple Quartet, the student asked me, “How is that a gradual process?” I said, “It’s not. It’s not a gradual process.”

I think people suffer from a misconception, not only about me, but about music theory and its relation to music practice. Whatever music theory you encounter, certainly including the rules of four-part harmony, was written after a style had been worked out by ear, and by a good musical ear. Of course its good for a student to learn the rules of four-part harmony, but with the understanding that they’re just student exercises and that parallel fifths may be perfect in another context. All music theory refers to something that has already happened, but if it is taken as a prescription, or worse as a manifesto, heaven help you. It’s interesting that the music we treasure most of Schoenberg preceded the 12 tone theory. It’s no accident that Op. 11, and “Farben” of the Five Orchestral Pieces Op. 16 (my favorite piece) or Pierrot Lunaire, and other earlier works all keep getting played. They’re “difficult” and they’re dark, but they’re more successful, I believe, than those pieces that came later with the adoption of the 12 tone system.

Yet, you are constantly asked to explain minimalism because it’s legitimately part of your early style, and others have since assumed this style.

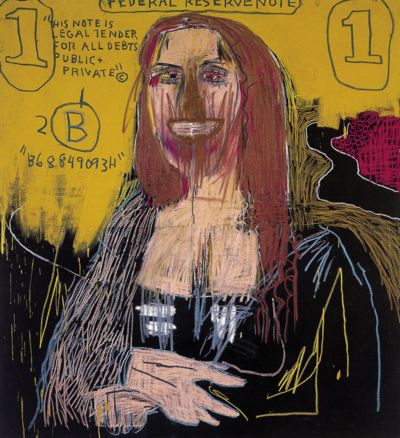

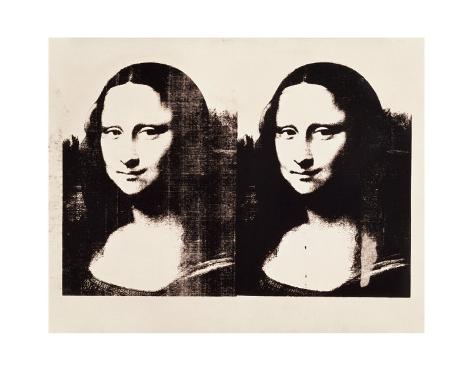

The point is, if you went to Paris and dug up Debussy and said, “Excusez-moi Monsieur…are you an impressionist? ”, he’d probably say “Merde!” and go back to sleep. That is a legitimate concern of musicologists, music historians, and journalists, and it’s a convenient way of referring to me, Riley, Glass, La Monte Young, maybe even John Adams, and now Arvo Pärt, Giya Kancheli, and Louis Andriessen; it’s become the dominant style. But, anybody who’s interested in French Impressionism is interested in how different Debussy and Ravel and Satie are – and ditto for what’s called minimalism. So it’s hard to get excited about that kind of thing. Basically, those kind of words are taken from painting and sculpture, and applied to musicians who composed at the same period as that painting and sculpture was made. There is some validity to the description; certainly if you listen to Piano Phase or Violin Phase and you look at Sol LeWitt, you’re going to note some similarities. That just means people who are alive at a certain period of time and have their antennas up and functioning are going to get similar input messages and they’re going to react to that those messages. Beyond that, it’s all individual, and that’s what’s interesting.

There is a wonderful visual side to Music for 18, in the way one performer takes over an instrument from another performer. Is that an important aspect of performing Music for 18?

Well, a lot of that is just keeping the key players in the ensemble doing what it is they do best. The title says it’s music for eighteen musicians, and we [Steve Reich and Musicians] play it with eighteen, but no other ensemble plays it this way. Eighteen is the minimum number of musicians with which you can do the piece. We are a traveling ensemble, which means that one extra person is one more air fare, hotel room and so on. When the Ensemble Modern does it, I think they do it with twenty-one. When we do it, I play marimba in three sections, and piano in the others. Jim Preiss, who plays the vibraphone and does all the cueing, also comes over and plays piano, and Jay Clayton, who sings, plays my piano part when I’m playing marimba. Other ensembles wouldn’t bother with that. You can use up to twenty-two people, and the number of musicians will vary from ensemble to ensemble. When you see us doing it, we’re just the original instruments. [laughs]

There’s no conductor , and that was a pivotal decision. The models I had in mind were West African drumming and Balinese gamelan. The conductorial responsibilities for eighteen people playing together and making changes together devolves onto members of the ensemble. Primarily the vibraphone and first bass clarinet. Basically, what you have is chamber music where everybody has to listen to each other, be aware of each other, because there’s a lot of audible internal cueing, most obviously by the vibraphone and the bass clarinet. This creates an atmosphere where you have to be in touch with each other or you can’t play the piece. There is also a kind of communal aspect to that, which musicians genuinely enjoy.

My ensemble has been together for a long time. We know each other well and that just comes out when you see us perform. I think that reality is communicated perhaps best in Music for 18 Musicians. People in the ensemble have to feel at ease with each other in order to keep on playing together for 10, 20 or 30 years. There is a kind of shared attitude in terms of what it’s all about when we’re playing; we don’t talk about it – its just there.

TEHILLIM (1981)

How did you choose the four psalm verses that form Tehillim?

I had a rekindled interest in my own religious background in Judaism starting around 1974. By 1981, I really had a desire to bring it into my music in some way. I thought that the most obvious way was to set a text in the original Hebrew, and the most obvious text to set was the Psalms.

The Psalms are the most musical texts that we have in Judaism. They were written by King David, who was a great musician of his time. We know they were sung by Levites. I am a Levite—some of us in Judaism know whether we are a descendent of that Levitical family—and so I would have been a musician way back when. Therefore, setting the Psalms was a very natural thing to do, and the added bonus was this: as opposed to the Torah and the Book of Prophets, which have traditional melodies, the traditional melodies for singing the Psalms have been lost amongst the Ashkenazim; that is, the European Jewish traditions. They have been maintained among the Yemenite Jews, but I’m not a Yemenite and am not that familiar with their tradition of singing. I know of their tradition of singing and I’ve used some of it in The Cave, but I didn’t grow up with it. Therefore, it was kind of a green light for me to compose, without having to ignore or incorporate some kind of pre-existing melody.

That was the basic idea for setting the Psalms. Now, which ones to set? There are 150 of them; very good question. I took the book of Psalms in Hebrew and English, put it on the piano, and started going through the whole book. My idea was to pick a text that I could say to anyone, Jew or non-Jew. In other words, it had to be a very universal text, and the ones I came up with were ones I felt comfortable saying to anyone.

When going through the book of Psalms, were you more drawn to particular textual features such as repetition of words like “yóm-le-yóm” or striking imagery?

No, the only requirement I had was that I could look someone in the eye, whoever they would be, and say this. That was my only criterion. Of course the text had to be something that got to me as well. I knew two of the selections from the Sabbath prayers. The first, The heavens declare the glory of God, is part of what you say every Sabbath; and Who is the man who desires life is another part of that same Sabbath prayer. I was familiar with those, so that made them immediately appealing.

Is there an underlying structure to the whole work?

What underlies the whole piece and what really makes it work is the use of groups of twos and threes in a totally free arrangement. This was done entirely by ear, depending on how I heard the syllables of the Hebrew. Ha-sha-my-im meh-sa-peh-rím ka-vóhd Káil became 1-2, 1-2-3, 1-2, 1-2-3, 1-2, 1-2-3, 1-2. I had never heard music like that in my head before.Tehillim was a discovery. I had certainly heard Stravinsky and particularly the Bulgarian rhythms that Bartók used, which are full of 5/8s and 7/8s, but my use of changing meters, as a non-stop continuity, began in Tehillim.

Tehillim groups very large measures and some conductors [laughs] are not too happy about that. There was some discussion, and there is still some thought in my mind, that it might be easier if there was no bar larger than 7/8. One could re-bar it, there’s no question about that, but the reason it’s barred the way that it is, is because that’s the way the melodies go.

Groups of twos and threes, changing in all kinds of groupings throughout a piece, became a staple in many works I’ve done since. Once I did it in Tehillim, it became part of my vocabulary, and I began to use this in different ways. In Tehillim, everybody is moving more or less homophonically, except in the canonic sections. It’s used in a totally different context in the second and fourth movements of The Desert Music, where you have groups in the brass playing conflicting parts of twos and threes and interlocking together, a kind of gamelan in changing meters. This creates something in between a repeating pattern that is always varying and an accompanimental texture. Groups of twos and threes are also used in Sextetand Triple Quartet. I’m just using it now in Bikini and will undoubtedly use it in Dolly as well.

Is there a thematic arrangement to Tehillim? You start with Psalm 19, then move to Psalm 34, back to Psalm 18, and finish with Psalm 150.

The first movement, The heavens declare the glory of God, is basically Abraham looking up at the sky and intuiting that there’s got to be some intelligence, some consciousness behind all of this—it all works too perfectly. It’s not just the sun, it’s not just the moon, it’s the whole universe. There seemed no other way for me to start.

The second movement switches to human character: “Neh-tzór le-shon cháh may-ráh”, “keep your tongue from evil”, “va-ah-say-tóv”, “and do good”, “ba-káysh sha-lóm”, “seek peace”, “va-rad-fáy-hu”, “and pursue it”. It’s very, very difficult not to speak what’s called in Hebrew, le-shon ha-ráh.

the evil tongue. We’re all guilty of it. It’s not a good human character trait and it’s widespread. Its instances have been detailed very carefully in Judaism because avoiding it as much as you humanly can is considered a very important moral value. The second movement is about that and everything associated with it.

What happened with the third movement is [laughs], I was in a situation where the first two movements were being done by themselves in Germany, at the South German Radio Station in Stuttgart. Peter Eötvos, the conductor, and I were driving together, and he was basically asking me, “Are you going to continue in the same tempo?” I knew from the way he put it that he was saying, “Can’t you give us a break?” [laughs] Respecting Eötvos, I decided to insert a break and actually stop the music after Parts I and II, and then go on in a slower tempo.

Now, as you may know, I don’t generally write movements. I don’t believe in movements. I believe that when the music stops, it stops. In any event, I came back and decided to set the 18th Psalm, with that extremely interesting text [reciting bits of the Hebrew and English]: Im-chah-síd, tit-chah-sáhd, If righteous G-d treats them righteously, im-ga-vár ta-mím, ti-ta-máhm, if almost perfect G-d treats them almost perfectly, im-na-vár, tit-bah-rár, if upright G-d treats them uprightly, va-im-ee-káysh, but with the perverse, tit-pah-tál, G-d is subtle. Musically, it’s set in parallel [sings im-chah-síd, tit-chah-sáhd and im-na-vár, tit-bah-rár with parallel melodies].

Actually, the model for that third movement is a soprano and alto duet from the Fourth Cantata of Johann Sebastian Bach, Christ lag in Todesbanden. There’s a back and forth exchange between the two voices, as there are in so many of the cantatas, and then a kind of resolution between them. That was the model for Im-chah-síd, tit-chah-sáhd. The four singers in Tehillim are divided into pairs and respond to each other. As a matter of fact, the doubling of the four voices with first the clarinets, then later with oboe and english horn, was also a steal from that same cantata. Bach, like many great composers before and after him, doubled the voices for support. It’s an old trick, and it’s one of the best in the book; it makes the singers confident because they know the pitch is there. If you treat the voices that way, and I do, and also amplify everything, boosting the oboe and english horn, then you get what my producer Judy Sherman calls the “voicestrument.” So, when you hear the singers doubled by clarinets at the end of the first movement of Tehillim, and then thatimmediately changes to being doubled by oboe and english horn at the beginning of the second movement, it’s a completely different vocal timbre.

The last movement, of course, is the 150th Psalm. There’s a coda on Hallelujah, which is the text that’s been set more than any other in the history of Western music, so that was a challenge. I really wanted to set it. It’s deliriously overjoyed and it refers to tóf u-ma-chól,

drums and winds , which is precisely what I was using in the piece. It was too good to miss. As a matter of fact, now I’m remembering, I finished that Hallelujah in my studio where I’m sitting now, here in Vermont. I wrote a lot of the piece here, but most memorably, the ending. I knew I had it. [laughs]

An important technique you use in Tehillim is canon, an outgrowth of your earlier phasing technique.

Phasing is a word that I coined, but all it really refers to, is a variation of canonic technique. “Phasing” is simply a canon using a short melodic pattern, as opposed to an extended melody, where the rhythmic distance between the first voice and the second is flexible and gradually changing. Piano Phase is a variable canon at the unison. It’s a unison canon where the rhythmic distance between the first voice and the second voice is flexible. Similarly in Violin Phase and Drumming. In Tehillim, instead of there being a melodic pattern, there are real full-blown melodies. Then everyone said, “Oh, those are canons.” But canons are canons. Sometimes the subject is short and that’s what people hadn’t heard before; that’s why it seemed to be different. The principle is exactly the same as Sumer is icumen and Row, Row, Row Your Boat, but instead of having a longer melody you have a short pattern.

There are some long stretches of canon in the first and fourth movements of Tehillim, and you punctuate the long stretches with harmonic changes. Would you say you were particularly more sensitive to the vertical aspect in this work than in previous works?

Well, I had to deal with a piece that was going to be harmonically unified over a relatively long period of time, so of course I was, but I don’t think I mapped it out the way I did for Music for 18 from beginning to end like a cycle. I just worked with the melodic material and then tried to figure out ways to harmonize it. Ain-óh-mer va-áin de-vah-rím, Without speech and without words, Beh-lí nish-máh ko-láhm, Nevertheless their voices heard, from the first movement, is a particularly good example of that. I felt that here I wanted to be able to mirror the text in the music. What happens is that the whole melody is reduced to just four notes: G, A, D, and E. Those four notes by themselves are very harmonically ambiguous, and consequently you find that there are changes of key. So, Without speech and without words/Nevertheless their voice is heard was something that was open to interpretation, looking at the world around you, and this is mirrored in this particular section by simply creating a very ambiguous scale that is capable of harmonic reinterpretation.

Then there is the Hallelujah in D Major. What’s interesting about the ending of Tehillim is that it ends on the dominant, and it’s a dominant eleventh chord. Like Four Organs, the tonic is on top and the dominant on bottom, which gives you that sense of the music still going on even when it ends.

What makes a good ending, in your view? Tehillim sustains such a remarkably tireless energy that it’s hard to anticipate its end.

Oh, it’s a complete setup. I don’t think there’s a better ending that any one could write for that piece. A good ending, for me, tries to avoid a V-I cadence. I was guilty of it at then end of the Four Sections, but alas, I couldn’t think of anything better to do. Outside of that, there’s no formula for anything. My early pieces are processes in that when they’re done, they’re done. But again, those are satisfactory endings because the whole piece is about a process. Therefore, when the canonic process returns to unison, as in Piano Phase, it’s a perfect way to end. Tehillim is very traditional Western music key-wise, and in many other respects. Hallelujah in D major certainly seems like a good way to end.

You said that setting Psalm 150 was a challenge, not because you had to deal with Judaic tradition but with Western musical tradition. Did you encounter other difficulties while writing Tehillim?

I think I encountered most of the difficulties even before I started composing Tehillim. When I first put the Psalm texts in front of me, after I figured out which ones I was going to set, it was as if they were talking to me: “Well, Handel gave me this, Bach gave me that, Britten gave me this, Stravinsky gave me that – what have you got in mind?” It was like I was being picked up by the scuff of the neck and asked, “Where’s my melody?” Once it got going though, it was a complete revelation.

Tehillim is one of those pieces where I did something entirely different in a big way. When I was first working on it my wife said to me, “You’re actually singing! [laughs] You’re singing melodies with words!” It was the first time I wrote melodies in that sense. Tehillim is about melody. It was exciting to do something absolutely different after having worked for about fifteen years with melodic patterns. I had been writing melodies in a very short form: – very good melodic module in Piano Phase, not quite as good in Violin Phase, and very good rhythmic module that lent itself to very good melodic configurations in Drumming. All those little modules, they have to be gold or else you’re dead. Melody is always, in some sense, the main element. There are a lot of melodic patterns in Music for 18 Musicians. They’re short, but they become extended and work very well melodically. Tehillim is melody in a recognizable way in Western traditional terms, and that was the break. That really drove the piece and it ended up being a very inspired piece.

Tehillim took a while to write because it was long, and writing a slow movement was also new for me. In addition, I hadn’t set a text to music since I was a student, and had never done it successfully as a student. So, finally I was setting a text that I was excited about, and it was really working. What the singers were doing in works like Drumming and Music for 18 was doubling an instrument and using vocalise to become part of the musical ensemble; they weren’t singing words. Tehillim is the first piece where I said, “Okay, singers are going to sing words and the instruments are going to accompany them.” Singers love singing the piece and that’s extremely gratifying. It’s certainly one of the best pieces I’ve ever done.

Why had you avoided using melody?

Basically, I had been interested in getting rid of melody and accompaniment, the whole homophonic model, and saying, “I am dealing entirely in a contrapuntal situation of short repeating patterns.” Everything comes out of that web of melodic motives, not really melodies but melodic patterns. That worked very, very well. Tehillim was saying, “Let’s see what happens if you just apply that kind of thing to extended melodies.”

DIFFERENT TRAINS (1988)

How did Different Trains originate?

It started out with Beryl Korot, the video artist (and my wife) saying to me, – after I had been commissioned by Betty Freeman to do a piece for Kronos Quartet, “Well, you’re so interested in the sampler, why don’t you use one? You’ll love it and they’ll love it.” I was given a number of sampling keyboards from the Casio Company—this was back in the 80s—and I was very excited about the possibility of using samples in my music. You see, after I finished with the tape pieces, I basically had no interest in technology: I was not interested in synthesis; I was not interested in something sounding like a violin. The only time I ever used synthesizers was for convenience—in The Desert Music, the brass notes are so long and the performers need to breathe – so I have the synthesizers doubling them so you don’t hear the holes; in Sextet, it’s because I would have had to tour with four woodwinds to get the same effect. But, back then, samplers presented the possibility of bringing non-musical material into musical contexts by playing or programming it. Different Trains was the first and inspired result.

I knew I would do a piece for sampled voices and Kronos Quartet, but I didn’t know whose voice it was going to be. At first, I thought it was going to be the voice of Béla Bartók, and I went and got a recording that he made at WNYC years ago during the time he was at Columbia University. He was also at Boosey & Hawkes, but there turned out to be a problem with rights, at which point I just said to myself, “Do I want Béla Bartók looking up over my shoulder while I try to write a piece for string quartet? It’s hard enough as it is.” Then I thought about using the voice of Ludwig Wittgenstein because I had studied his philosophy and imagined that he must have had a very interesting voice. But after corresponding with people in the United States and England, nobody knew of Wittgenstein recording anything. He would have had to do it with a wire recorder and it turned out that he hadn’t.

Then I began thinking there must be something closer to home. Somehow, these train trips that I had taken as a child between New York and Los Angeles just popped into my head. I began asking myself, “When did I do this?” and, “What was going on at that time?” Well, that was 1939, 1940, 1941, and what was going on at the time was little Jewish boys like me were put on trains from Rotterdam or Brussels or Budapest to Poland and they never came back.

That was the genesis of the idea, and once I had that I moved pretty quickly. I spoke to the woman who had taken care of me as a child, who at the time was living in Queens. I located a black Pullman porter in Washington, D.C. who had been on the very same lines that I had ridden on as a child. Then I went up to Yale, where they have an archive of Holocaust survivors on tape. I spent a couple of days up there just riveted. I copied what I felt were not only riveting stories but stories told in a musical tone of voice. Then I came back and went through all this material, stopping every time I got to something that seemed emblematic—“Nineteen forty-one”—emblematic in what it said, and emblematic in the speech melody of how it was said. I put these on a floppy disk and wrote them down as best I could in musical notation. After all this, I formulated some basic rules of thumb: every time a woman speaks the viola doubles her, every time a man speaks the cello doubles him; the train whistles are always doubled by the fiddles. The whole thing just took off after that.

This is one of the first works in which you invite the listener into your personal story. As a listener, I find it intensely moving to think that of the many things evoked in this work, one of them is you remembering yourself as a three- or four-year-old. Do you have reservations about putting something so personal in your music?

You have to put something personal in every piece you ever do. You mean in terms of the verbal material? Well, it isn’t really there. All that’s really there is what I tell you in the program notes, if you have the program notes. One of the nicest reactions to Different Trains was by Pat Metheny, during the time that I was working with him on Electric Counterpoint. He didn’t have any program notes, so he didn’t know what the piece was about. After he heard Different Trains he said to me [speaking quietly], “Man, that was an unbelievable piece.” I said, “Could you hear the words?” He said, “I heard enough to get the sense of it.” He didn’t understand everything that was said, and he had no idea of my background, but he got it. I gave him a big hug and said that was the best thing I had heard because it meant that the piece works without program notes.

Nobody receives awards for technical expertise in music. We know that Bach was perhaps the best technician that ever lived, but he himself said das Affekt, and if Bach said das Affekt, I can only say it don’t mean a thing if it ain’t got that swing or that je ne sais quoi. That’s what matters, and Different Trains, thank G-d, has that. There are some interesting things going on technically but that’s not why we’re talking.

Did you have reservations about setting your personal experiences against the historical backdrop of the Holocaust?

To consider using the Holocaust as subject material in any way, shape, or form is so inherently…not just difficult, but impossible. What makes this piece work is that it contains the voices of these people recounting what happened to them, and I am simply transcribing their speech melody and composing from that musical starting point. The documentary nature of the piece is essential to what it is.

PROVERB (1995)

How did you end up uniting Pérotin and Wittgenstein in Proverb?

What happened is that Paul Hillier and I were in correspondence for a number of years, and to make a long story short, he ended up conducting The Cave. Sometimes the singers would rehearse parts of the work by themselves, and Paul just loved the canons. He told me that I should do a vocal piece, and because he knew that I was interested in biblical material, he suggested I set Song of Songs. After considering it, I decided it was just too much, a mammoth undertaking. I wanted something really short and aphoristic. I started looking through the book of Proverbs, but I couldn’t find exactly what I wanted. Then I got a book of world proverbs, but found so many different things that I didn’t know what to do with them. At the time, I happened to be re-reading Culture and Value, a collection of Wittgenstein’s writings, and when I came upon one sentence—“How small a thought it takes to fill a whole life!”—I thought to myself [slapping his hands together], “That’s it!” Now, it’s not really a proverb, but it’s proverbial in tone. The ideal way to convey the meaning of that short text was to make it an augmentation canon so that it would grow longer and longer and fill up all the available space. Proverb is an homage to Pérotin and it’s the first time I ever composed a piece using another composer as a model. I dealt with Pérotin because I was writing for Paul Hillier and his group, Theatre of Voices—it was later premiered at the Early Music Festival in Utrecht in 1995. Proverb calls for the same kind of voices I had worked with in my previous music.

Pérotin, as you know, has been a great source of inspiration and instruction to me over the years. This time I actually had Viderunt omnes on the piano, and wrote some of it out on one staff—there is a very nice Kalmus edition that Ethel Thurston did several years ago. What was exciting, of course, was looking at the Pérotin very closely and seeing exactly what I would and wouldn’t use. What I did use were the tenors singing melismatically on a given syllable. What I didn’t use was the crossing of the voices. Also, instead of having the drones sung by other tenors, they are sung by women’s voices while the men sing the melismatic parts—of course Pérotin only worked with men’s voices because women’s voices weren’t used until much later in history.

Interestingly, the male and female parts don’t interact until towards the end.

Right. Basically, you have the women and then you have the men, and then you have women and men. In the last section, the long extremely augmented canon, you’re quite right, the women and men sing more or less simultaneously. The women hold their long tones and the men sing melismas on that held tone. Once again its a piece that uses rhythmic groups of twos and threes. In that sense Proverb is similar to Tehillim in that you have two vibraphones creating interlocking two and three beat patterns as the drummers were doing in Tehillim.

Augmentation is kind of a subtext in a lot of my music. The first use of it was in Four Organs, which was also done under the influence of Pérotin. In Pérotin, and in Léonin too for that matter, you basically have notes of Gregorian chant that are stretched out to enormous proportions. Four Organs began as a sentence on paper: “Short chord gets long.” WhatProverb is really about is augmentation canon, which is something that Pérotin did not do as such. In Proverb, you start with melodic material and canon, and when the canons augment to enormous proportions, you get almost shifting clouds of harmony because each tone is held out so long that it just feels like suspensions and chords that don’t resolve. Augmentation was something I’ve worked with for a long time. It’s present in Music for Mallet Instruments, Voices and Organ, as you can hear quite clearly, and to a lesser extent in Music for 18 Musicians. After I finally wrote an augmentation canon in Proverb, I immediately used that technique again in Three Tales.

In terms of where I come from in the Western music tradition, certainly from Bartók and Stravinsky in this century, but I’ve also always relied heavily on medieval techniques. The uses of canon and augmentation are at the top of that list.

TRIPLE QUARTET (1999)

Bartók is, as you say, someone you feel close to. In Triple Quartet, I hear a lot of his influence, particularly Bartók’s dance finales from works like Contrasts and the Fourth Quartet.

The Fourth Quartet! The third movement of my quartet begins as a result of the fifth movement of the Fourth Quartet! You know, the cellos doing all that offbeat stuff. Now, Bartók can get more going in one string quartet than I can with three, but nevertheless, I was saying to myself when I wrote this, “Wouldn’t it be great to keep that energy going?” The fifth movement of the Fourth Quartet is definitely the starting point for Triple Quartet. I didn’t use any of Bartok’s notes, but I tried to keep that kind of energy going.

Was Bartók the only composer who influenced Triple Quartet?

Well, I probably had a little influence from Michael Gordon, too, his Yo Shakespeare, which has conflicting rhythms going against each other. In Triple Quartet, the second and third quartets are often playing in dotted quarters and the first quartet in half notes so that you get conflicting rhythms in the accompaniment, sort of forming their own polyrhythmic music.Also, while I was writing the piece, my friend Betty Freeman sent me a new two CD album of the Kronos Quartet playing the complete Schnitke quartets. I hadn’t heard a note of his music and while listening to his quartets I certainly didn’t feel close to most of what he was doing – with the exception of the incredibly beautiful Mesto in his Second Quartet. The effect of listening to his quartets while I was beginning work on Triple Quartet, was quite interesting. It was as if he was pushing me to thicken the plot and particularly the harmonic language. In fact this was exactly what happened – so I have to thank Betty and Schnitke for that. Sadly, Schnitke died about a month after I began listening to him.

There is a very specific harmonic progression that you use throughout Triple Quartet. Is it significant that E Minor, G Minor, Bb Minor, and C# Minor is an interval cycle that forms a symmetrical chord?

Well yes, but I had no desire to stress the diminished seventh chord. I wanted to arrange my key centers in a way whereby I could modulate in an interesting way. Harmonically, I wanted minor dominants because of the ambiguities of raised seventh, lowered seventh, the augmented second between the lowered sixth and the raised seventh, and so on. The idea was to keep each section of the piece in that same world – yet differently, and not to outline the diminished seventh as such. I keep to minor keys and dominants throughout, so that the whole piece is like shifting dominant pedals. There is nothing like the propulsive energy of sustained dominants. When you modulate in minor thirds you don’t really have a sense of harmonic movement. You do, however, get a feeling of freshening up the atmosphere because you are changing key. So, it’s a way of getting variety yet keeping the overall sound remarkably homogeneous and most of all always having that forward energy that only a dominant can deliver. What’s also nice about the harmonic movement from C# Minor to E Minor, to G Minor, to Bb minor, and so on is that those are, for me, very intuitive modulations.

What happens in Triple Quartet is that first we go through each of the four different keys in four different meters: 4/4, 12/8, 3/2, 3/4. Then we go through the same cycle of keys again, but in changing meters within each harmonic section, in 7/8, 5/8, 6/8, 2/4—that kind of metric change. When that’s finished, there’s a slow movement, which is back in E Minor, and then the last movement starts in G Minor, and finally ends up again in E Minor.

Is it correct that Triple Quartet is a long-planned extension of your Counterpoint series?

Not really. It exists in three versions. One is for two pre-recorded quartets, and one live one, as Kronos does it. Then it can be played just by three live quartets, twelve players in all and it can also be done by 36 players from an orchestral string section. I suspect that in the long run it will be done more live than electronically. So far that’s been the case.

Before I did Different Trains, I had thought that I would write a piece for multiple quartets for Kronos Quartet. I knew I wasn’t going to write for one string quartet because I’m not interested in one string quartet. For me, it doesn’t have enough multiples of the same instrument. Where’s the second viola and second cello? I was going to write a piece for Kronos for three quartets, but then the sampling idea came along. The multiple quartets are in Different Trains, but they’re not the main dish; the main dish is the sampled voices, and all the musical material is derived from them. By the time I was going to write another piece for Kronos, this earlier idea came back to me, and I thought now is the time for a Triple Quartet. Also, it was very important for me at that time, – since it was basically written as a break between Hindenburg and Bikini,- to get away from sampling, to get away from electronics, and just deal with instruments. Triple Quartet is a completely musical piece, and perhaps that was partly why the energy is so strong and so good. It was a much-needed pit stop. I think it’s a great piece. I’m very, very pleased with it.

THREE TALES (1997-2001)

Describe your recent collaboration with video artist Beryl Korot, Three Tales.

This afternoon I was just working out the coda for Bikini, and beginning the interviews for Dolly. Well, Three Tales is “Hindenburg,” “Bikini,” and “Dolly”—early, middle, and late twentieth-century events in technology, respectively. There are three tenors, two sopranos, and ten players: four percussionists, two pianos and string quartet.

Hindenburg is in four discrete scenes so the formal organization reflects that period in history. It opens with the crash, goes back to the construction, then to a the final flight over the Atlantic, which is witnessed by an old lady, Freya von Moltke. She is the widow of James von Moltke, who was hanged for his part in the plot to assassinate Hitler. She lives right outside of Dartmouth, near us in Vermont. She said [in a hushed voice], “A very impressive thing to see! Have you seen pictures?” [laughs] She was great. Then the crash happens again at the end and is shot on the ground. The vocal music here is mainly the three tenors, technology being primarily a male enterprise until recently.

Bikini takes a totally different approach, with the atom and hydrogen bomb tests in 1946-1954 in the Marshall Islands in the South Pacific. Beryl Korot suggested the formal organization which is basically, three sound/image blocks: the B-29 in the air; on the island with the Bikini people; and on the American ships. This cycle of three ‘blocks’ is repeated three times with a coda that shows the unfortunate results of the tests It’s a meditation on the whole event, rather than just going through scene 1, scene 2, scene 3, etc., as in Hindenburg. As we move chronologically and historically, we change the formal organization of the music and video. The coda at the end, where the countdown finally gets to zero – you don’t hear the bomb, you don’t see the bomb; what you hear is this very sad music and what you see is palm trees against the garish orange of the Hydrogen bomb light slowly disintegrating one frame gradually dissolving into the next. Looks like an abstract expressionist rendering of palm trees being slowly, painfully blow to bits. The guy who’s doing the countdown finally reaches, “Zzzz-eeeeee-rrrrrrr-oooooooo.” Real slow motion sound. Have you read that early book of mine, Writings about Music?

Yes, of course.

I wrote something in there called, “Slow Motion Sound.”[1] Well, now you can do slow motion sound on your desktop. Slow motion sound occurs throughout Bikini. I also use the technique in Hindenburg with the voice of the famous announcer, Herb Morrison, describing the crash. In Dolly it will be taken to more extreme proportions.

Dolly of course hasn’t happened yet, but the plan for Dolly is to go back to interviews as source material as we did in The Cave . Everything will be in state-of-the-art digital color, whereas everything that preceded it in the previous two tales was archival footage from the 1930s, the late 1940s to the early 1950s. Beryl and I will go out and interview biologists, people in artificial intelligence, robotics, and a few religious figures.

The individual tales get longer and longer, and Dolly will be the longest tale. The Cave dealt with interview material that was presented very straightforwardly, in keeping with the religious matter that was the subject matter there.

Along with slow motion sound there will also be another new technique I call stop action sound. Its the exact equivalent of a freeze frame in film. As somebody is talking, one vowel becomes a held tone as for instance, ‘zerooooooooo’. Then somebody else starts talking while the previous speaker’s vowel tone is still held. It becomes part of the harmony of the piece. It also reflects what happens when someone says something to you that gets to you emotionally. The conversation continues, but you still keep part of your mind on what was said before,

What is the vocal style that you choose for Three Tales?

The vocal style that I choose, as one of my singers puts it, is basically a style anywhere from Ella Fitzgerald to Alfred Deller. It’s basically the kind of non-vibrato, small voice that you find in early music or jazz. Therefore, these singers are not opera singers, but singers involved in the early music world, who share a light voice, are generally aware of how to use microphones, are very good part singers, and are very accurate rhythmically. To me, they feel like the voices of our time more than the operatic bel canto voice. To use bel canto voices without taking into account that they conjure up Italy or Germany of the 18th and 19th centuries can lead to something inadvertently humorous. If you’re writing an opera about, let’s say, President Eisenhower, and you have his character come out and sing like he just stepped out of the Marriage of Figaro, people can obviously take that as a joke.

Have you referred back to The Desert Music at all while working on Bikini, since in the former work you chose a text by William Carlos Williams that captured his sentiments regarding the dropping of nuclear bombs?

Nuclear war has been hanging over our heads since the Cold War. Today someone could enter New York with a satchel full of biological, chemical, or radioactive material. Given Islamic fundamentalist extremists we are all now keenly aware of this as a real threat. It’s Gonna Rain was done two years after the Cuban Missile Crisis when it was a real possibility that we were all going to go up in radioactive smoke. Kennedy and Khrushchev were facing off and the Russians were going to put missiles in Cuba. Every composer is subject to the realities that are going on around him or her. I was interested in Williams, a doctor and a poet who wrote: “Man has survived hitherto because he was too ignorant to know how to realize his wishes. Now that he can realize them, he must either change them or perish.” He really hit on something that goes back to Faust regarding knowledge. Sometimes now very impressive scientific people say there are things that we shouldn’t do. We’ve never thought about that before, but now we have to because they are so dangerous. We have to account for human error, which is always with us. Dolly, will be dealing with that. So yes, sure, they are connected thoughts.

Is the documentary material in Three Tales treated differently than in Different Trains or The Cave?

Oh yes, totally. Different Trains is an homage to the living and the dead. As they spoke, so I wrote. It was the same with The Cave. The people in The Cave are discussing religious matters that I and others take quite seriously, and I just felt again that I was the faithful scribe. The result is constantly changing tempos and keys. No rhythmic momentum or harmonic constancy.

The basic assumption with Three Tales is just the opposite; make the samples fit the music—prima la musica. Allow the musicians to build up a head of steam and have some rhythmic momentum, as I have in most of my other music – and let the samples kind of rain down on them. The material of Three Tales was perfect for this because it was just interesting documentary material and I could do whatever I wanted with it. The result is a more musically driven work. Also, frankly, I got tired of doing the other thing. I didn’t want to continue constantly changing key and tempo.

Does this approach leave you more room to make some musical commentary on the speech material?

Well, I’m always presenting commentary on the speech material. There’s not much speech material in Hindenburg, but for example, I stretch out Herb Morrison’s words: “It flaaaaaashhed [dropping in pitch] and it’s crashing!” What this does as you’re watching this huge zeppelin burning and coming down in slow motion is give you a feeling in the pit of your stomach. What he’s saying is intensified because you hear all the glissandos that are in his vowel sounds, this irrational stuff going on against the tenors, who are singing three-part canons on the words of the German ambassador to the New York Times when asked about the crash, “It could not have been a technical matter,” which of course it was. The tenors are singing this first as a short melody and then as an elongated canon. As they’re singing these long tones, which are rather similar to those in Proverb, Herb Morrison’s line comes out with these sliding vowel smudges on top of it. I’m use the voice to suit the real emotional subject matter at hand.

What motivated you to broach these three ambitious topics?

Beryl and I were asked to do a piece about the twentieth century by Dr. Klaus Peter Kehr, who had been involved in commissioning The Cave. We went to subject matter that really got our juices flowing, where we knew we could stay involved for three or four years! We started Three Tales in 1997 and after it was finished I took a break and composed Triple Quartet and a little vocal piece Know what is above you, from mid 1998 to mid 1999. Then we got to work on Bikini. It will be a total of about four years of work and projected for completion in mid 2002.

It seems that current events really get your juices flowing.

Not exactly. When we did The Cave, which is about Abraham and his family, we started it in 1989. Shortly thereafter came the Gulf War and everybody said, “Oh you’ve got to show it soon!” I remember on the front page of The New York Times there was a shot of a missile base near Basra and it said, “Missiles Near the Site of Abraham’s Birthplace” because Abraham was born in Ur, which is basically in Iraq, near Basra. It was tempting to get involved, but we didn’t. The story of Abraham and his family is still very much with us today because what’s going on in the Middle East is primarily a religious war, and it’s taken on various political forms over the years. But the answer to your question is, no, we didn’t get involved in the Gulf War, and no, we didn’t get involved with the peace process, because we had a classical story to maintain and basically everything was in that story and to diverge from it to current events was just foolish.The stories we’re dealing with here in Three Tales are not at all stories like that, but the human character flaws they delineate have been with our species from the beginning.

Why “tales,” any reason behind that?

Well, the word “tale,” as opposed to “story,” gives you a slight feeling of apprehension. Chaucer used “Tales” as did Flaubert and theirs and ours are all cautionary tales.

“Tale” suggests some kind of moral lesson. Are there lessons in your work?

Any good art that is about something may have lessons embedded within it, many of which may be unknown to the artist making the piece. We are presenting some very real things that have been, and still are, going on around us. People will draw their own conclusions based on the revelations of character that occur while watching and listening to these scientists and religious leaders on the screen.

What are some modifications that you’ve made to Three Tales since your initial conception and since Hindenburg toured by itself as a work-in-progress from 1997-9?

When Hindenburg went out by itself, it was really a mistake, as it would be to present the first act only of most any opera. On the other hand, it was useful to us. We have now eliminated Scene 2, “Mythic Stature,” a long scene that was a history of the man Paul von Hindenburg from World War I up through the rise of Hitler. It was just a little too heavy-handed. What used to be the third scene, is now the second. “Nibelung Zeppelin,” uses the Nibelung leitmotif from Das Rheingold as its basis. I essentially wrote my own version of the Wagner staying close to his melodic and harmonic original. What you see are the actual workmen building the Hindenburg in Friedrichshafen in 1935, but cut out by Beryl in this incredible way so that they’re apparently climbing over a kind of erector set, which is actually the Hindenburg metal structure. At the end, you see masses of workers with heavy ropes pulling out this gigantic thing with huge swastikas on the fins. With the Wagner hammering away at the same time it’s genuinely an interesting, appropriate comment. – And it’s only about three minutes long.

Also, in the early planning stages we were thinking of using the Challenger disaster, but wee soon decided, that was one disaster too many. Then Dolly was cloned, and we both looked at each other and said, ‘That’s it.” It opened up the whole medical enterprise, most of which is very positive. It would be absurd for those of us who use computers every day, benefit from modern medicine and countless other scientific advances to take a completely negative attitude toward technology. On the other hand, Dolly clearly points to the ambiguities that come with technology. Changing the human species – are we up to the job?

One of the underpinnings of this entire project, which I haven’t mentioned yet, but which appears in Bikini and Dolly, are the two creation-of-human beings stories in Genesis. The first is the well-known story of humans given dominion over the fish of the sea, the birds of the air, and everything that moves on the face of the earth, which is also related to eventually making atom bombs. The second story is quite different; G-d took a lump of dirt and [gathering his hands together] breathed life into it and then put the man into a garden with the woman. It says in the Hebrew, l’avda u l’shomra to serve it and to keep it, to maintain it, which are of course a very different set of marching orders.

Those are two different stories?

Yes, the first is in Genesis 1 and the second in Genesis 2 giving you another aspect of who we are.

Do you have other projects currently planned for the future, after Three Tales?

There are a number of things, and I don’t know exactly what the order will be. Kronos wants me to write a big piece for them, like a half hour or forty-five minute piece. I’m thinking about writing a cello counterpoint with multiple cellos, since multiple cellos basically offer an orchestral texture and at least an orchestral string texture because of the range of the instrument. The cellist will probably be my advisor from Bang on a Can All-Stars. Anne Teresa De Keersmaker, the dancer in Belgium, wants a short piece, which unfortunately she wants more or less now. I don’t know if I’m going to be able to do it, but we’ll see. Also, it seems to me that there are going to be ensembles like the Ensemble Modern but happening here in America, such as this Ossia Ensemble, which is of course poetic justice because it’s my ensemble and ensembles like it that were the original models for these groups. That is, ensembles of 20 or 30 musicians who are professional, who are aware of popular, non-Western music, and are highly trained, first-rate players. I think there is going to be a very important group like that coming out of some context that I’m involved in now, and I might write the first piece for that ensemble, which would also specialize in pieces working with media and live musicians. Also, I imagine that after a good period of time Beryl and I will do a third collaboration.

Do you prefer to have several pieces that you’re working on at the same time?

No, I’ve never worked on more than one piece at a time; with the exception of Six Pianos and Music for Mallet Instruments, Voices and Organ, which I did compose at the same time. I’m also beginning to understand that there are two basic kinds of work that I’m interested in; music theatre pieces using video and sampling, and purely musical pieces like Triple Quartet. I need that balance, alternating between the two, to keep my energy up.

How do you get through times when it’s difficult to compose, if you have times like that?

Oh, I certainly have periods when it’s difficult for me to compose. I go downstairs and have a cup of tea, or I go out for a walk. When I was younger and I hit a problem I used to think, “I’ve been lucky up to now, but now its over [laughs].

I think it’s very important for artists in general to be self-critical. Of course there’s a point where if you’re too self-critical, you’re in trouble. But I’ve known a couple of artists, who shall remain nameless, who were very talented and potentially first rate, but because they thought that anything they did was just fine, they ended up producing a lot of poor or mediocre work. I think that a judicious sprinkling of self-criticism is essential, to do really good work in any field.