Saisha Grayson

Agitprop!: A Conversation with Martha Rosler, Nancy Buchanan, and Andrea Bowers

Saisha Grayson: Because we think of you all as co-curators of this exhibition, I wanted to start by talking about how the invitation to nominate a fellow artist struck you when we first presented that as part of the invitation to participate in an exhibition. It’s sort of an unusual model.

1

MR: It threw me into an absolute panic. It took me ages to answer. There were so many aspects of art and activism to consider, not to mention the title of the show, which is “Agitprop!”

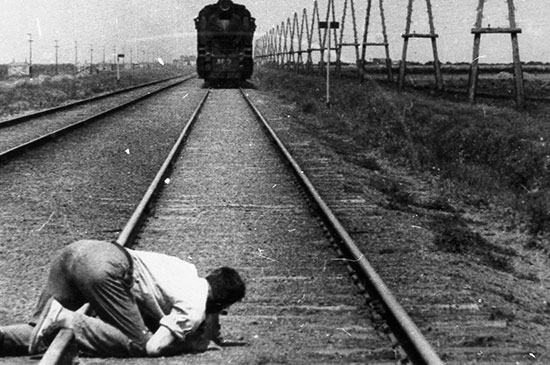

Artist and activist Michael Zinzun reports for Message to the Grassroots, 1992.That’s a very specific type of address to the public. I’ve been an ardent supporter of Nancy’s work for decades upon decades, ever since we knew each other in California. Her work is complex, always political in every aspect—feminist and other forms of activism, as well as always embodied. Political thinking pervades everything she does.

Because of the “agitprop” part of the brief, I thought that it would be really important to highlight Message to the Grassroots, which was an hour-long, monthly television show she hosted and coproduced with activist Michael Zinzun, every month in LA, for nearly ten years, until it was brought to a close by Michael’s untimely death in 2006. It was a show which I thought spoke to every audience, but certainly to the present one. And for many reasons, it exemplified not only Nancy’s commitment to speaking, if you’ll allow me, to the grassroots, but also her feminism in her collaborative relationship to it, and her willingness to sort of take a backseat in its public presentation.

Nancy Buchanan: When I was thinking about who to nominate, actually very quickly I thought of Andrea because her work always involves an activist group. She has managed, somehow, to bridge so many different issues with her work, and yet still present things that are elegant, that are beautiful, but that bring in a lot more than just the artwork. Usually, there’s a component that involves some kind of activity out in the real world. So that people come away not just educated about the issue, but able to contribute to change.

Andrea Bowers: I didn’t have to curate anyone. But I’m so honored to be in this chain, because I think one of the most important things for me, as an artist, is the ethical aspects of it. And I think there’s probably five artists who I really look to for guidance in these issues. And two of them are sitting on the stage right now.

SG: I was hoping you might talk a little bit about how each of you decided it made sense to fuse your activism and your art. For some of you that’s something that happened right away, and for some of you, art and activism were separate practices that merged later on.

NB: Well, when I was an art student, I was also demonstrating against the war in Vietnam. And then I realized that I didn’t have to compartmentalize my life, that I could bring the subject right into my practice. That was an amazing revelation at the time, because it wasn’t a very popular thing at that moment in some art circles. Since then, one of the central questions that I’ve always had is: How can the individuals responsible for some of the problems that we see think the way they do?

When I met Michael, I was actually doing community art workshops in the city of Pasadena. They had just set up their cable television station. And I did these workshops for adults and children. And I’d met Michael on an art panel, actually, in an exhibit. And then, later on, just as I was planning to leave the Public Access Corporation, he walked in and said, “I want to produce a show.”

And I said, oh, great. I’d like to help you. And that was that. When I went on to work at CalArts, we had a public program where artists and students went out into the community and did their workshops with a partner organization. I was in the Film School, and I was partnered with the Watts Towers Arts Center. And I said, well, if I’m going to go to this center, I would like a collaborator who really knows this community. And so I said I would only do it if they also hired Michael. So we also did these workshops together with people down in Watts, which included some of the members of the groups that came together in the historic gang truce in 1992. And so that was part of our show and also part of our workshops.

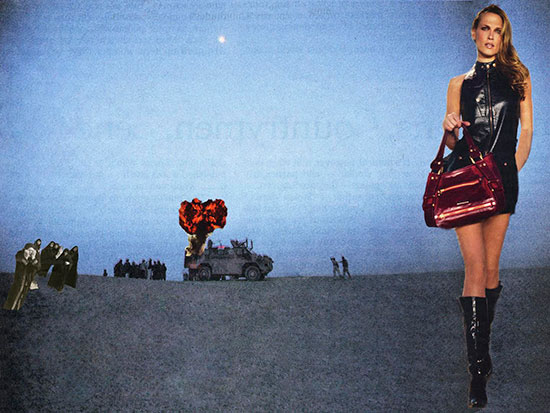

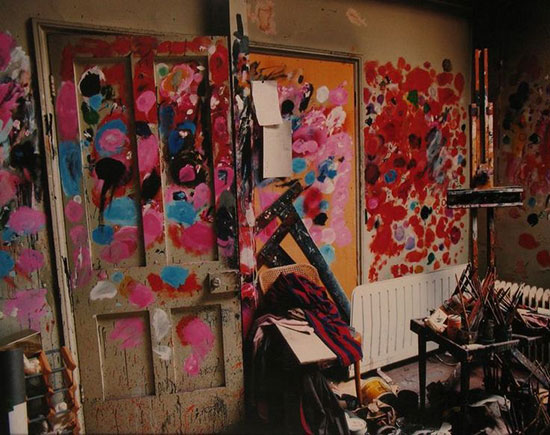

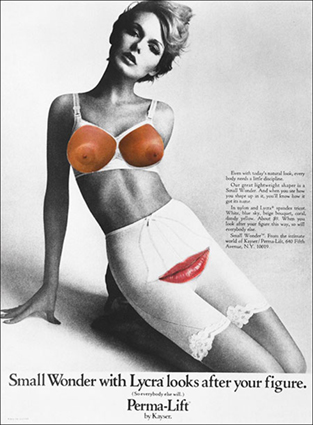

Martha Rosler, Afghanistan (?) and Iraq (?), (Detail), 2008. Photomontage. This image constitutes the right half of a diptych.

Martha Rosler, Afghanistan (?) and Iraq (?), (Detail), 2008. Photomontage. This image constitutes the right half of a diptych.SG: Very cool. And Martha?

MR: Yeah, art and activism. I grew up about ten blocks from here, in Brooklyn, and when I was a junior in high school I was an Abstract Expressionist painter in training. The Brooklyn Museum hosted an art school that was, one could say, pitched at Sunday painters. But, I was a high school kid, and anyway, there were serious painters teaching there. And that’s where I was as an artist when I also became a protester, first, against having to take cover for air raid drills, which I always thought was ridiculous. As though we can hide from nuclear bombs! But it was illegal to not take cover in those days, to be standing in a public space when you were supposed to be cowering in a cellar.

But it took me a while to integrate any kind of subjectivity, aside from an abstract one, into my work. It first happened, actually, in my use of photography, because I had gotten the idea that abstract painters dealt with narrativity by taking photographs of things, in real everyday life.

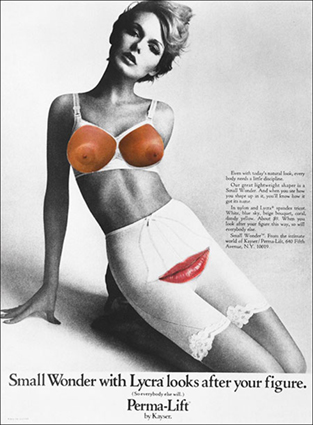

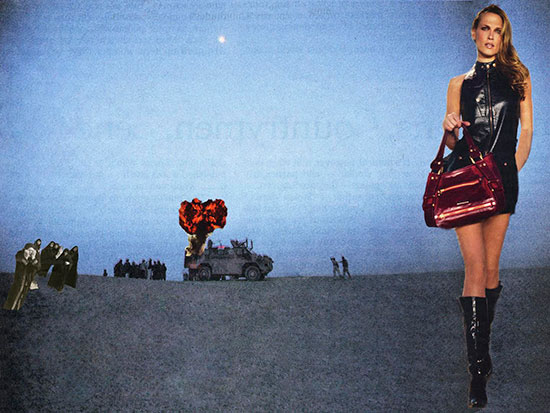

Martha Rosler, Untitled (Small Wonder), 1972. Photomontage.

Martha Rosler, Untitled (Small Wonder), 1972. Photomontage.

I think feminism was the first activist practice that made a direct appearance in my work, when I started making montages of the representation of women in magazines and newspapers, especially in ads. It was always a question of how representation produces and promotes and carries forward a picture of who we are. But one day, sitting at my mother’s dining room table, looking at a photograph of a Vietnamese woman swimming across the river with a child, desperately trying to escape, it occurred to me that that kind of imagery was central to trying to talk about who are we, and who are the supposed “theys” on the other side. And I realized that I could incorporate this idea into the work that I was doing. But it took me about six or seven years to quit the painting, which I carried on simultaneously. But at that point, I was doing activist work, which I kept out of the art world. I have to say it was not intended for the art world. It really was agitprop!

SG: This definition of agitprop came up during the nomination discussion. You said that it means something quite specific to you, that it refers to how something is distributed, where it lands originally. You also mentioned being an abstract painter. Andrea, you mentioned that male activists, in your opinion, were sometimes like abstract painters. Can you talk a little about where that critique comes from?

AB: From studying with many feminists? I went to school and studied with Millie Wilson. Nancy was there. And also with Charles Gaines and Michael Asher.

I became really aware of issues of subjectivity, and that that was the standard modernist methodology for how you work. What did Pollock say? That he was painting his internal arena or something like that? It just seemed that if that was the standard, then women and artists of color just didn’t live up to it. And so I didn’t want to work that way. I wanted to throw that out the window.

So in almost all of my work, there are jabs at these involuntary, expressive, emotional, dysfunctional men that are celebrated in the art world. Once I became really involved in activism I realized that these same personalities existed there too, especially in climate justice and environmentalism. Just because I was doing activism didn’t mean I was overcoming patriarchy or mansplaining. So I’ve been making some work that comments on that.

Andrea Bowers, Radical Feminist Pirate Ship Tree Sitting Platform, 2013. Recycled wood, rope, carabiners, misc. equipment and supplies. Photo: Nick Ash.

Andrea Bowers, Radical Feminist Pirate Ship Tree Sitting Platform, 2013. Recycled wood, rope, carabiners, misc. equipment and supplies. Photo: Nick Ash.SG: This one you said is a radical feminist pirate ship.

AB: Yeah. I got arrested for tree sitting in Arcadia, California. There was a forest of 250 pristine oaks and sycamores. I’d never walked on ground like that, where no one’s ever walked, it was this really soft kind of growth. Plus it was pitch black, because we were breaking in at four o’clock in the morning. There were four of us, including this young man named Travis who spent three of the last six years as an Earth First! activist living in a tree in Northern California.

He doesn’t really make money living in a tree. He’s doing really good work, but he has no money. So, every once in a while, he would call and say, do you have any work for me? And I said, well, sure, let’s make some sort of pimp-my-ride tree-sitting platforms, because when you’re in a tree, you can’t sit on a tree branch for a year. You have to have a platform up there. And I thought it would be really funny to make these really accessorized tree-sitting platforms.

And I just see them as super, elaborate, ornate, political posters, because they’re covered in slogans, and they’re just really entertaining. Often, you can sit in them.

So I had said to Travis, “Travis, so what’s your dream tree-sitting platform?” And he was like, “A pirate ship.” And I got so pissed off because I would never have thought of that. Of course a guy would make that. I just don’t have that mentality. So then, I thought, I’ll make this radical, pirate, tree-sitting platform. There is this amazing quote from Mary Daly where she says:

Ever since childhood, I have been honing my skills for living the life of a radical feminist pirate and cultivating the courage to win. The word “sin” is derived from the Indo-European root “es-,” meaning “to be.” When I discovered this etymology, I intuitively understood that for a woman trapped in patriarchy … “to be” in the fullest sense is “to sin.”

But then I found out that Mary Daly wrote—and it was a long time ago—a lot of transphobic comments. And I didn’t know that. I hadn’t done my research properly, and so that’s kind of the problem with the piece, which I decided to correct with this show, actually, that’s up now.

SG: That’s always an interesting question, sort of how I think all of you have so many intersexual—intersectional—issues.

AB: We do.

(Rosler laughs)

SG: Intersexual, intersectional, they’re all of a piece. There’s an origin in feminism, but it leads you to many different places. How do you prioritize when you’re across-the-board concerned about economic injustice, environmentalism, racial issues? How do you move between these?

NB: I’ve been, in the last many years, actually, really concerned about money and consumption. And so, for me, it’s like, how can I bring the issue of commodification and consumerism really upfront? What’s a new way to do that? Because that’s at the bottom of so much that’s wrong.

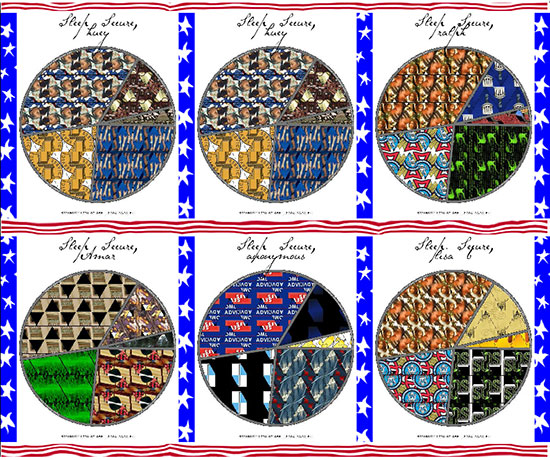

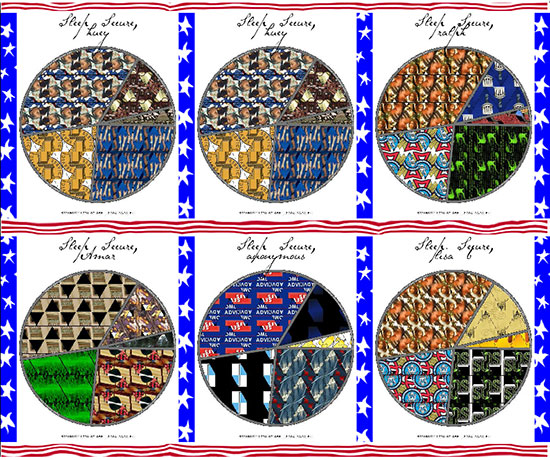

It’s the problem with police brutality. It’s the problem with housing. It’s the problem with most everything, these issues of disempowerment and inequality. And so, because of how widespread a problem it is, there’s always a new way to represent it. The image is from a web-based piece that was called Sleep Secure, which invited visitors to the website to create a pattern inside one of the slices of the annual pie chart made by the War Resisters League.

Every year they make a pie chart to show you what US taxes are spent on. I tried to find web-based images for these different categories, so you could click on one of the slices and kind of play with it. You could make a pretty pattern. But you could also print out that pattern and make your own real, physical—as in, not-virtual—quilt. You could save your decorative pies on the website, and share them, too.

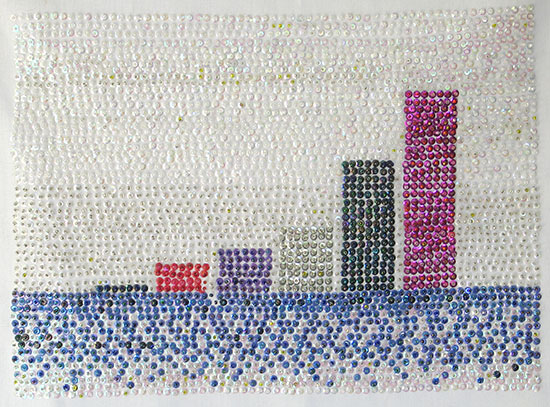

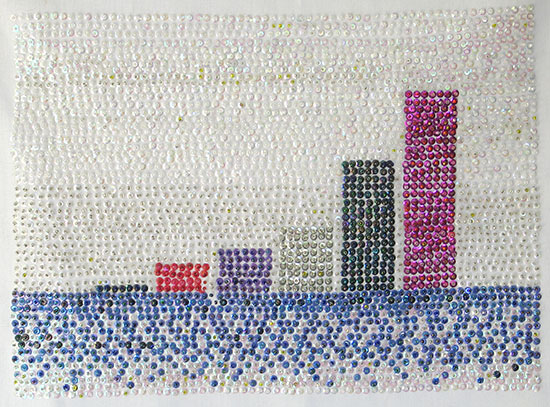

I like to use humor with things, when I can, and make them playful. The image is a flag embroidered with sequins representing income inequality. I had glommed onto George H. W. Bush’s statement about voodoo economics. And I thought, okay, all right, let’s make some voodoo flags about economics.

Nancy Buchanan, Income Increases, 2002. Embroidery with sequins.

Nancy Buchanan, Income Increases, 2002. Embroidery with sequins.SG: Martha, your Garage Sales are also a feminizing of an economic critique, or getting at international economics by way of the domestic.

MR: There’s an extensive, direct quote from the chapter on commodity fetishism in volume one of Capital that played continuously throughout each of the Garage Sales. I understood that when you say to someone, “Here’s some cheap stuff!” they’re not listening to somebody talking about commodity fetishism. But it represents an unacknowledged background to a general critique.

But this, in and of itself, is a playing out of the tacit underpinnings of our lives, which are often neither audible, nor visible, even though they’re in our face every minute. Which is kind of what Nancy was talking about when both she and Michael were pointing out, bluntly, how neoliberal capitalism basically controls who we are and how we inhabit our social spaces.

AB: Martha, the night before last you were talking about the cycle of visibility for women artists, about being invisible for decades and then suddenly visible when they want the old broads back again.

MR: Yes, every actress will tell you this as well. As a young female, you’re a phenom, the talking dog. Like: “Wow! She’s got this shape, and that shape, and this shape! (gesturing) And she talks. She walks. She acts. She makes art! Look at that. Wow.” And then, in middle age, the bloom’s off the rose. That was then, they say. And then, when you’ve reached a certain age, it’s: “Look, she’s still alive! Maybe we should go talk to her before she stops being alive.”

There’s nothing that has changed. But if I point this out to men, they may say, “But I disappeared, too … ” No, you didn’t.

SG: From inside the art world, what do you feel like you can you do? What would you like to see change that we should be working on?

AB: Equality. I think it’s visibility and it’s economics. Personally I would, of course, love to get rid of patriarchal capitalism. But that’s probably not going to happen immediately. That’s going to take a longer time. But in the meantime, I would like to see women have equality with men, and have the same visibility, and also survive, financially.

SG: Very often, each of you are building platforms and creating spaces for other people to present and talk. And I want to open up the conversation about how this connects to feminism, because very often, I think, we do feel conscious about our own invisibility and how that is created. With the result being that feminist artists are constantly creating platforms and making space for other people to speak, too.

NB: I think that it’s a matter of deeply feeling and understanding our connection to other human beings. That’s it. It’s not me struggling to be at a certain level in the art world, or anywhere else. It’s a real visceral, literal connection. We’re all going to sink. Or we’re going to change.

AB: I don’t know. I learned about an alternative practice through feminism in the Seventies, studying you guys and some of your early practices. Why can’t we have models of collectivity? Why can’t we start to question authorship in some way? It’s about learning, too. I need to be around other artists I respect so I can grow and learn. Nancy’s always calling me: “There’s this protest,” “There’s this talk.” She keeps me on my toes. I need that. That’s what I need community to help me with. It’s sort of selfish, in a way, for personal growth. I’m so grateful for it.

MR: Obviously, the art world is driven at base by the fact that it’s a market economy. And the institutions within it have to figure out how to carve out spaces that are relatively insulated from the payment structure.

Every institution tries to open up a space of autonomy within itself. On the tour I conducted at the Frieze Art Fair as one of its artists’ projects, I forgot to have the group interview a dealer. We did everybody else. Every single person, from the toilet keeper—there is a famous toilet facility at the Frieze—to the sandwich people, security, the newspaper, the accountants, the Royal Parks rep., and the doorkeepers at the VIP Lounge, and the VVIP Lounge. But I forgot to talk to the dealers, which I admit was idiotic. But those financial constraints can never be cast aside.

And obviously, the museum world is driven by donors and by budgets that come from places where people don’t look kindly on stuff that doesn’t fit with that desired aesthetic separation between the street and the museum. And there’s something to be said for that.

There’s a constant negotiation of how we make a space within these places. Curators have to answer to that same structure. You can’t do a show because you feel like doing a show. You have to sell it. It has to go up the chain of management like anywhere else, and often this takes years.

There was a moment of relative democratization, in the US and beyond, in the ‘70s, when we had artist-run spaces at a time when artists were developing apparently noncommodifiable forms in a bid for autonomy from the market. And then the dealers reestablished—I mean this quite literally—the market, with neo-neoexpressionist painting, reestablished a certain kind of control over the whole system. The government funding for artist-run spaces was yanked, which meant that we, then, had to be cast back on the kindness of established institutions.

But because of the gigantic floods of money currently flowing everywhere through the economy, art fairs actually supplanted the exhibition model, and this has made things a lot worse. The art fair model is not too concerned about ethics. I mean, business centers on people with big bucks who can buy a Wu-Tang album and stick it in a drawer, or whatever the hell it is.

Martha Rosler, Frieze Art Fair (Walking Tour of Sites of Labor), 2006. Performance.

Martha Rosler, Frieze Art Fair (Walking Tour of Sites of Labor), 2006. Performance.AB: Is that what they’re buying?

NB: There was a great moment at one of the recent LA art fairs where some younger artists, Audrey Chan and Elana Mann, remounted Suzanne Lacy and Leslie Labowitz’s piece about myths of rape. And so, at this cocktail reception, when people were enjoying themselves and having their drinks, they were accosted, or confronted, by young people carrying colorful signs and talking about how this is a myth about rape, and here’s the truth. It was a nice collision, I thought.

SG: That’s an interesting example, because it touches on the usefulness of history in your projects. You work with archives a lot. You revive the structure of certain strategies. Why are we not learning from history? Or, how we can learn better from history, through a look to the archives, or by looking to the older performance projects that are in danger of being lost?

AB: I think archiving accidentally fell into my lap because most of my projects sort of start with an activist that I learn about, just through circles of friends, or I seek out, because I see they’re doing something. And I email them, or I try to get a hold of them.

But what I started finding out was that all of these activists that I would go and interview in videos—because I almost always interview in videos, because I’m trying to create literally an archive of activists, during my lifetime, that I think are amazing and may be underrepresented—but what I discovered was, in all of their closets, or in all of their drawers, were these amazing archives that no one was seeing. So I just asked them if I could scan them. I’d give them all the scans back. And then, that started circling into social media and stuff. And then, I’m collecting all of that stuff, too. But it’s really about under-recorded, underrepresented, under-seen, really important historic events, because activism doesn’t end, right? These actions don’t end.

MR: That’s right.

AB: People work their lifetimes doing different things. But the issues keep coming up again and again and again. So it’s important to look back.

Nancy Buchanan, Sleep Secure, 2003–4. Interactive web project for The Alternative Museum; this is a detail of quilted income tax pie charts created by users.

Nancy Buchanan, Sleep Secure, 2003–4. Interactive web project for The Alternative Museum; this is a detail of quilted income tax pie charts created by users.MR: There’s a trend in academe, and perhaps elsewhere, to critique the idea of collaboration, and participation. And interestingly, a number of these attacks on inclusiveness have come from female scholars, which I always find interesting. I did write a little bit about it in the book that I did on the culture class, in part to agree with the idea that somehow public projects wind up being social management tools for social and political elites.

But it’s a mistake to make a totalizing criticism of a process that’s actually very porous—the idea of inviting other people into whatever space you’ve been accorded for whatever amount of time.

Let’s say you are working with people who have not otherwise been given access to a public space to represent themselves. You never want to speak for people, which is a serious issue. So how to name them in the production of the work? Repeatedly, when I’ve invited other people to collaborate with me, I’ve run into a problem with the curators and the art space who refuse to acknowledge the collective authorship of the work. The problem of saying, “no, it’s not a work by me. It’s a work by me and this person, and this person, and this person, and this person, and this person.”

Noah Fischer, who I see in this audience today, with Occupy Museums, has managed to write a contract in which the institution acknowledges the co-authorship of the other people who have participated in a project, because otherwise you wind up, against your will, with people seemingly in a subordinate relationship to you, because of the way the institution insists on naming the author of the work, whom they call “the invited artist.” This is something not talked about publicly, the way that institutions insist on controlling the record, telling artists, “We nominated you. You don’t have the right to nominate anyone else,”—But the partial departure from that model is what makes this particular exhibition, Agitprop!, unique.

SG: Thank you. And I want to add, Interference Archive, which is in the show and has this great poster that says, “We Are Who We Archive,” gave us a wall label with sixty people’s names, every single person who was involved in that group during that period of time. Because we’re not trying to shut down [crediting] based on the market-driven interest to name one artist in relation to this.

NB: My friends Christine and Margaret Wertheim, who made the Crochet Coral Reef, which has traveled around the world, felt that the reason why some places didn’t want to take their work, and why there’s no market for it, is that they insisted on listing every single name of every person involved as being a part of that work. They would not allow it to be represented as “by Christine and Margaret Wertheim.”

MR: This is a kind of an ossified mindset that comes from people who have been trained, and rightly, to verify historical facts. They become so stuck in the fetishization of the shards of evidence that they have trouble stepping backward to an actual larger event, or a larger piece of evidence. Hence this problem of segmenting out the artist as the one who gets nominated. And everybody else is, well, who the hell are you?

SG: And focusing on the fetishized object instead of the issue, or the moment, or the event that’s being brought up. Speaking of fetishization, I read a number of interviews with each of you in preparing for this. And almost in every case you guys are asked to speak to the efficacy of activist art. “Did you successfully end the war, or stop patriarchy through your work?,” and so on.

AB: Yes, we did.

NB: We did.

SG: Yeah.

NB: War’s gone.

SG: Okay. Good. So that’s settled. I was wondering if your beginnings in activist feminist spaces helps avoid the expectation of totalizing successes or failures.

MR: Well, activism is a process. And we’re dealing here in a world of objects, art objects.

AB: I mean, activist change is inherently about collectivity, right? We’re back at that idea again. So all you can do is do your part. You do your part. You speak up, as a citizen—

MR: You took the word right out of my mouth!

AB: —and you trust that there are others who are like-minded who are out there working as hard as you are. And together, over time, change will occur. Chris Carlsson, who is an activist from San Francisco has spoken of radical patience, of knowing that it was started before you arrived and that it will continue after you are gone.

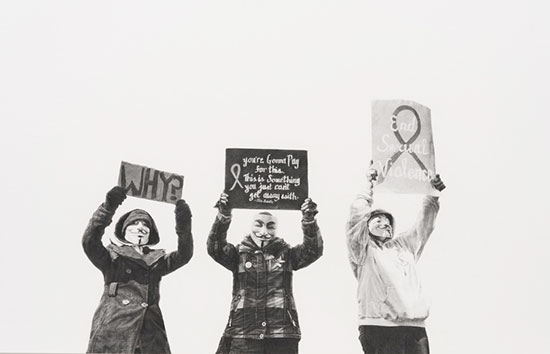

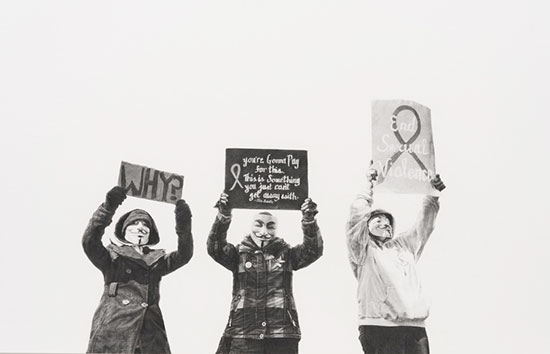

Andrea Bowers, #justiceforjanedoe, Anonymous Women Protestors, Steubenville Rape Case, March 13–17, 2013,2014. Graphite on paper. Courtesy of the artist and Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects. Photo: Robert Wedemeyer.

Andrea Bowers, #justiceforjanedoe, Anonymous Women Protestors, Steubenville Rape Case, March 13–17, 2013,2014. Graphite on paper. Courtesy of the artist and Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects. Photo: Robert Wedemeyer.NB: I have a quote from Michael Zinzun which I think is really important. Michael founded the Coalition Against Police Abuse in 1976 and was tireless as a worker and an advocate working with families whose children, or loved ones, had been injured or killed by the police. He called for a lot of changes that we still need to make today regarding racial profiling and demonizing young people. And he ended this speech that I found by saying: “We won’t struggle for ya. But we will struggle with ya. We can bring some lessons and experience to the struggle, but the most important one is that the people are their own liberators.”

SG: That’s great. Thank you.

MR: I want to say something about art.

SG: Okay, great.

MR: Because you asked specifically about art and “did you guys stop the war?” And I want to affirm that I think art is revolutionary. I truly mean that, and I think we probably all do. But art doesn’t make revolution. People make revolution. And it’s as citizens, as Andrea said, that we struggle. And if our art is imbricated and implicated in that struggle, that’s what we do. But it’s still people who make the revolution, whatever that revolution is.

×

© 2016 e-flux and the author

Martha Rosler, Untitled (Small Wonder), 1972. Photomontage.

Martha Rosler, Untitled (Small Wonder), 1972. Photomontage.