Périodiques

Afterimage. Rochester, New York (Etats-Unis), Visual Studies Workshop, depuis 1973.

Art Com. La Mamelle, San Francisco, Calif. (Etats-Unis), Contemporary Arts Press, 1975-1979.

Art in America. New York (Etats-Unis), depuis 1913.

Art on screen. New York (Etats-Unis), Program for Art on Film, depuis 1992.

Art press. Paris (France), depuis 1972.

Artforum. San Francisco, Calif. (Etats-Unis), depuis 1962.

Artweek. Castro Valley, Calif. (Etats-Unis), McCann Publ., depuis 1970.

Avalanche. New York, (Etats-Unis), Center for New Art Activities, 1970-1973.

Beaux-Arts Magazine. Levallois (France), éd. Nuit et jour, depuis 1983.

Cahiers du cinéma. Paris (France), Editions de l’Etoile, depuis 1951.

Camera obscura. Berkeley, Calif. (Etats-Unis), depuis 1976.

Chimaera. Hérimoncourt (France), CICV, Centre international de création vidéo, Montbéliard Belfort (France), depuis 1991.

Cøil : journal of the moving image. Londres (Royaume-Uni), Proboscis, depuis 1995.

Community Video Report. Washington, D.C. (Etats-Unis), Washington Community Video Center.

Contrill’s filmnotes : a review of independent cinema and video, Melbourne (Australie).

East Village Eye. New York (Etats-Unis), Eye Production, depuis 1979.

Environmedia. Venise (Italie), depuis 1972.

Felix. New York (Etats-Unis), depuis 1991.

Film Quaterly. Berkeley, Calif. (Etats-Unis), University of California, depuis 1958.

Frieze. Londres (Royaume-Uni), depuis 1991.

Fuse. Toronto, Ont. (Canada), Arton’s Publ., 1980-1986.

Gen-Lock. Genève (Suisse), Gen-Lock, 1986-1990.

Hybrid. Londres (Royaume-Uni), 1992-1994.

Independent Film and Video Monthly. New York (Etats-Unis), Foundation for Independent Film and Video, depuis 1978.

Kunstforum International. Wetzlar (Allemagne), depuis 1973.

L’Image vidéo. Paris (France), Editions Fréquences, 1989-1991.

Leonardo. Oxford, Ala. (Etats-Unis), Pergamon Press, depuis 1968.

Leonardo music journal. San Francisco, Calif. (Etats-Unis), MIT Press, depuis 1991.

Media Arts. New York (Etats-Unis), National Alliance of Media Arts Centers, depuis 1996.

Mediamatic. Groningen (Pays-Bas), Stichting Mediamatic, depuis 1986.

Metronome. Dakar (Sénégal), Londres (Royaume-Uni), Berlin (Allemagne), Bâle (Suisse), Francfort (Allemagne), Vienne (Autriche), Metronome Publ., depuis 1996.

Mouvement. Paris (France), depuis 1993.

Mute. Londres (Royaume-Uni), Pauline Van Mourik Broekman, Simon Worthington, depuis 1994.

Nomad’s land. Paris (France), Pays nomade, depuis 1997.

October. Cambridge, Mass. (Etats-Unis), Jaap Reitman, depuis 1976.

Octopus (suppl. de Mouvement). Paris (France), Hyacinthe, depuis 1993.

Omnibus. Paris (France), Omnibus l’avance artistique, 1991-2000.

Parachute. Montréal, Québec (Canada), Artdata Enr., depuis 1975.

Para-para (suppl. de Parachute). Montréal, Québec (Canada), Parachute, depuis 2000.

Performance Magazine. Londres (Royaume-Uni), 1979-1992.

Pix. Londres (Royaume-Uni), Pix, depuis 1993.

Pixel : le magazine des nouvelles images. Paris (France), Zao, depuis 1988.

Prototypes. Hérimoncourt (France), CICV, Centre international de création vidéo Montbéliard Belfort (France), 1991-1992.

Radical Software. New York (Etats-Unis), Raindance Corporation, depuis 1970.

Scope magazine. Veyrier (Suisse), 1992-1993.

Screen. Oxford (Royaume-Uni), Oxford University Press, vol. 37, n. 1, 1996.

SEND. San Francisco, Calif. (Etats-Unis), San Francisco International Video Festival.

Studies in Visual Communication. Philadelphie, Pa. (Etats-Unis), Annenberg School of Communications.

Trafic. Paris (France), Editions POL, depuis 1991.

Turbulences vidéo. Clermont-Ferrand (France), depuis 1991.

Vidéodoc’. Bruxelles (Belgique), Médiathèque de Belgique, 1976-1989.

Video guide : Vancouver’s Video Magazine. Vancouver, B.C. (Canada), depuis 1978.

Video Networks. San Francisco, Calif. (Etats-Unis), Bay Area Video Coalition.

Video Texts. New York (Etats-Unis), Anthology Film Archive.

Vidéochroniques. Marseille (France), IMEREC, Institut méditerranéen de recherche et de création, depuis 1991.

Video d’autore. Rome (Italie), Gangemi editore, depuis 1994.

Videoglyphes. Paris (France), Association Vidéoglyphes, depuis 1979.

Videography. New York (Etats-Unis), United Business Publ.

Vidéo ? vous avez dit vidéo ? Liège (Belgique), Cirque divers, depuis 1979.

Zapp Magazine. Amsterdam (Pays-Bas), depuis 1994.

Numéros spéciaux

” Audiovisuel “, Art press, hors série, Paris (France), n. 1, 1982.

” Aux frontières du cinéma “, Les Cahiers du cinéma, Paris (France), hors série, avril 2000.

” Electrosons = electrosounds “, Parachute, Montréal, Québec (Canada), n. 107, 2002 ; Para-para, suppl. de Parachute, 07-08-09-2002.

Flash Art International, n. 228, janvier-février 2003.

” Internet all over : l’art et la toile “, Art press, hors série, Paris (France), n. 2, 1999.

” Landscapes “, Felix : A Journal of Media Art and Communication, New York (Etats-Unis), vol. 2, n. 1, 1995.

” Mouvances de l’image = Image shifts “, Parachute, Montréal, Québec (Canada), n. 103, 2001 ; Para-para, supplément de Parachute, 07-08-09-2001.

” Nouvelles technologies : un art sans modèle ? “, Art press, hors série, Paris (France), n. 12, 1991.

” Nouvelles technologies “, Parachute, Montréal, Québec (Canada), n. 84, 10-11-12.1996.

” Où va la vidéo “, Cahiers du cinéma, Paris (France), hors série, 1986.

” Techno. Anatomie des cultures électroniques “, Art press, hors série, Paris (France), n. 19, 1998.

” Télévision et démocratie “, Chimaera : Les cahiers du Centre international de Création Vidéo,

n. 1 et 2, Montbéliard Belfort (France), 1991.

” Vidéo “, Art press, Paris (France), n. 47, 1981.

” Vidéo “, Communications, Paris (France), Editions du Seuil, n. 48, 1988.

” Video Art “, Art Journal, Londres (Royaume-Uni), vol. 54, n. 4, 1991.

” Video Art-Video Alternative “, High Performance, Los Angeles, Calif. (Etats-Unis), vol. 10, n. 1, 1987.

” Video Art Explorations “, Cahiers du cinéma, Paris (France), hors série, automne 1981.

” Vidéo des années 80 “, Film action, n. 30, 12.1981-01.1982.

” Video Issue “, Arts Magazine, New York (Etats-Unis), n. 4, décembre 1974.

” Video the Reflexive Medium “, Art Journal, Londres (Royaume-Uni), vol. 45, n. 3, automne 1985.

” Vidéo-Vidéo “, Revue d’esthétique, Paris (France), Klincksieck, 1986.

Quaderni del Museo dell’Accademia Linguistica, n. 24, Gênes (Italie), Accademia linguistica di belle arti (Italie), [n. consacré au langage vidéo].

” World Wide Video “, Art Design, Londres (Royaume-Uni), vol. 8, n. 7-8, juillet-août 1993.

Ouvrages spécialisés

D’AGOSTINO Peter, Transmission-Theory and Practice for a New Television Aesthetics, New York (Etats-Unis), Tanam Press, 1985.

D’AGOSTINO Peter, MUNTADAS Antonio, The Un-Necessary Image, New York (Etats-Unis), Tanam Press, 1982.

ARMES Roy, On Video, Londres (Royaume-Uni), New York (Etats-Unis), Routledge, 1988.

Nouvelles images, nouveau réel : cahiers internationaux de sociologie / sous la dir. de G. BALLANDIER, Paris (France), Editions PUF, 1987.

Film et vidéo 82-92 : catalogue / préf. de François BARR, Paris (France), Centre national des arts plastiques, 1993.

BATTCOCK Gregory, Minimal Art : A Critical Anthology, New York (Etats-Unis), E.P. Dutton, 1968.

BATTCOCK Gregory, New Artists Video : a Critical Anthology, New York (Etats-Unis), E.P. Dutton, 1978.

Cinéma et dernières technologies / sous la dir. de Franck BEAU, Paris (France) ; Bruxelles (Belgique), De Boeck Université, 1998.

BELLOUR Raymond, Eye for I : Video Self-Portraits, Independent Curators Incorporated, New York (Etats-Unis), 1989. Eye for I : Video Self-Portraits, Montréal, Québec (Canada), Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal, 1992.

BELLOUR Raymond, L’Entre-images : photo, cinéma, vidéo, Paris (France), Editions La Différence, 1990.

BELLOUR Raymond, L’entre-images 2 : mots, images, Paris (France), Editions POL, 1999.

BERGER Hans, BERGER René, L’art vidéo : défis et paradoxes, Lausanne (Suisse), 1974.

BERGER René, La Téléfission, alerte à la télévision, Paris (France), Casterman, 1976.

BEY Hakim, TAZ, The Temporary Autonomus Zone, Ontological Anarchy, Poetic Terrorism, New York (Etats-Unis), Autonomedia, 1991 ; TAZ, Zone autonome temporaire, Paris (France), Editions de l’Eclat, 1997.

BLOCH Dany, Art et vidéo, 1960-1980/82, Locarno (Suisse), Flaviana, 1982.

BLOCH Dany, Art vidéo, Condé-sur-Noireau (France), L’image 2-Alin Avita, 1983.

BONET E., DOLS J., MERCADER A., MUNTADAS A., En torno al video, Barcelone (Espagne), G. Gili, 1980.

BOYLE Deirdre, Video Classics : A Guide to Video Art and Documentary Tapes, Phoenix, Ariz. (Etats-Unis), Oryx Press, 1986.

BRUGEROLLE Marie de, L’enrichissement des collections du Musée national d’art moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou ; les nouveaux supports : vidéo-numériques, [diplôme, muséologie, Ecole du Louvre, 1992], Paris (France), Ecole du Louvre, 1992.

Connections : art réseaux média / textes réunis et présentés par Annick BUREAUD et Nathalie

MAGNAN, Paris (France), Ecole nationale des beaux-arts, 2002.

BURGIN Victor, In Different Spaces : Places and Memory in Visual Culture, Berkeley and Los Angeles, Calif. (Etats-Unis), University of California Press, 1996.

CAC, Critical Art Ensemble, The Electronic Disturbance and Electronic Civil Disobedience, New York (Etats-Unis), Autonomedia, 1994 ; La Résistance électronique et autres idées impopulaires, Paris (France), Editions de l’Eclat, 1997.

CADOZ Claude, Les réalités virtuelles : un exposé pour comprendre, un essai pour réfléchir, Paris (France), Flammarion, 1994, (Dominos).

CAGE John, Silence : lectures and writings, Middletown, Ohio, Wesleyan University Press, 1961. Silence : discours et écrits, Paris (France), Denoël, 1970.

CARDAZZO Paolo, LUGINBÜHL Sirio, Videotapes : arte tecnica storia, Padoue (Italie), Mastrogiacomo, 1980.

CAUQUELIN Anne, DUGUET Anne-Marie, KUNTZEL Thierry, MEREDIEU Florence de, WEISSBERG J.L., Paysages virtuels, Paris (France), Editions Dis Voir, 1988.

CELANT Germano, OffMedia : nuove techniche artistiche : video disco libro, Bari (Italie), Dedalo Libri, 1977.

CHARLES Daniel, Gloses sur John Cage : suivies d’une Glose sur Meister Duchamp, [nouv. éd. revue et augmentée], Paris (France), Desclée de Brouwer, 2002 (Arts et esthétique).

COLOGAN Guy, SIMONI Jean-Bernard, Passages de l’image [petit journal], Paris (France), Editions du Centre Pompidou, 1990.

COSTA Mario, Artmedia : rassegna internazionale de estetica del video e della communicazione, Salerne (Italie), Opera universitaria di Salerno, 1985.

COTTON Bob, OLIVIER Richard, Understanding hypermedia : from multimedia to virtual reality, Londres (Royaume-Uni), Phaidon, 1993.

COUCHOT Edmond, Images : de l’optique au numérique, Paris (France), Hermès, 1986.

CUBBIT Sean, Timeshift on Video Culture, Londres (Royaume-Uni), New York (Etats-Unis), Routledge, 1991.

CUBBIT Sean, Videography : Video Media as Art and Culture, Londres (Royaume-Uni), Macmillan Education, 1993.

DAGOGNET François, Philosophie de l’image, Paris (France), Librairie Vrin, 1984.

DE KERCKHOVE Derrick, Brainframes : Technology, Mind and Business, Utrecht (Pays-Bas), Bosch & Keuning, 1991.

DERY Marc, Escape Velocity : Cyberculture at the End of the Century, New York (Etats-Unis), Groove Press, 1996 ; Vitesse virtuelle, la cyberculture aujourd’hui, Paris (France), Abbeville, 1997.

DERRIDA Jacques, STIEGEL Bernard, Echographies de la télévision : entretiens filmés, Paris (France), Galilée ; Bry-sur-Marne (France), INA, 1996.

DOUGLAS Davis, SIMMONS Allison, The new television : a public-private art, Cambridge, Mass. (Etats-Unis), MIT Press, 1977.

DOWMUNT Tony, Channels of Resistance : Global Television and Local Empowerment, Londres (Royaume-Uni), British Film Institute and Channel Four Television, 1993.

DRUCKREY Timothy, Ars Electronica, Facing the Future, A survey of Two Decades, Cambridge, Mass. (Etats-Unis), MIT Press, 1999.

DUGUET Anne-Marie, Déjouer l’image, créations électroniques et numériques, Paris (France), J. Chambon, 2002 (Critiques d’art).

DUGUET Anne-Marie, Vidéo, la mémoire au point, Paris (France), Hachette, 1981.

Formation Art : Images de synthèse [colloque] / sous la dir. de Anne-Marie DUGUET, Paris (France), Université de Paris 1, 14-15 octobre 1988.

L’art vidéo 1980-1999, vingt ans du Video Art Festival, Locarno : recherches, théories, perspectives / sous la dir. de Vittorio FAGONE, Milan (Italie), Mazzota, 1999.

FIESCHI-VIVET L., Pratiques vidéo et plastiques godardiennes : élaboration de formes cinématographiques, [conférence suivie de débats], Cerisy (France), Centre culturel International, Cerisy la Salle, 14-21 juin 2001.

FOREST Fred, Art sociologique, Vidéo, Paris (France), UGE, 1977.

FORESTA Don, Mondes multiples, Paris (France), Boutique à signes, 1991.

FROHNE Ursula, Video cult/ures, multimedial Installationen der 90er Jahre, Cologne (Allemagne), DuMont, 1999.

GAILLOT Michel, La techno, un laboratoire artistique et politique du présent, Paris (France), Editions Dis Voir, 1999 (Sens multiple).

GALE Peggy, Video by artists, Toronto, Ont. (Canada), Art Metropole, 1976.

GANTY Alfred, MILLIARD Guy, WILLENER Alex, Vidéo et société virtuelle, Paris (France), Editions Tema, 1972.

GOLDBERG RoseLee, Performance Art from Futurism to the Present, New York (Etats-Unis), H. N. Abrams, 1988.

GOLDBERG RoseLee, Performance art, Londres (Royaume-Uni), Thames and Hudson, 1998.

GOLDBERG RoseLee, Performances, l’art en action, Londres (Royaume-Uni), Thames and Hudson, 1999.

GRAHAM Dan, Video-Architecture-Television, Halifax, N.S. (Canada), Press of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, 1979.

GROOS Ulrike, MÜLLER Markus, Make it Funky : Crossover zwischen Musik Pop, Avantgarde und Kunst, Cologne (Allemagne), Oktagon, 1998.

GRUBER Bettina, VEDDER Maria, Kunst und Video : internationale Entwicklung und Künstler, Cologne (Allemagne), DuMont, 1983.

HALL Doug, FIFER Sally Jo, Illuminating Video : An Essential Guide to Video Art, New York (Etats-Unis), Aperture, Bay Area Video Coalition, 1990.

Video culture : a critical investigation / sous la dir. de John G. HANHARDT, New York (Etats-Unis), Visual Studies Workshop Press, 1986.

Culture Technology and Creativity in the Late Twentieth Century / sous la dir. de Philip HAYWARD, Londres (Royaume-Uni), J. Libbey and Cy, 1990.

HELSEL Sandra K., PARIS ROTH Judith, Virtual Reality : Theory, Practice and Promise, Londres (Royaume-Uni), M. Westport, 1991.

HASENLECHNER Anja, Vorbilder und Nachbilder : Positionen österreichischer Künstlerinnen zu neuen Medien, Vienne (Autriche), Triton, 2001.

HENNION Antoine, La Passion musicale : une sociologie de la méditation, Paris (France), Editions Métaillé, 1993.

HERZOGENRATH Wulf, Videokunst in Deutschland 1963-1982 : Videoinstallationen, Video-Objekte, Videoperformances, Fotografien, Stuttgart (Allemagne), Gerd Hatje, 1982.

HERZOGENRATH Wulf, DECKER Edith, Video-Skulptur retrospektiv und aktuel : 1963-1989, Cologne (Allemagne), DuMont, 1989.

HERZOGENRATH Wulf, GAEHTGENS Thomas W., THOMAS Sven, HNISCH Peter, TV Kultur : das Fernsehen in der Kunst seit 1879, Amsterdam (Pays-Bas) ; Dresde (Allemagne), Verl. der Kunst, 1997.

Widerstände : Kunst, cultural Studies, neue Medien : Interviews und Aufsätze aus der Zeitschrift Springerin 1995-1999 / sous la dir. de Christian HÖLLER, Vienne (Autriche) ; Bolzano (Italie), Folio, 1999.

HOTZ-BONNEAU Françoise, L’image et l’ordinateur, Paris (France), Aubier-INCA, 1986.

The Media Arts in Transition / sous la dir. de Bill HORRIGAN, Minneapolis, Minn. (Etats-Unis), Walker Art Center, 1983.

Video : A Retrospective, 1974-1984 / sous la dir. de Kathy Rae HUFFMAN, Long Beach, Calif. (Etats-Unis), Long Beach Museum of Art, 1984.

JENKINS Henry, Textual Poachers : Television Fans and Participary Culture, Londres (Royaume-Uni) ; New York (Etats-Unis), Routledge, 1992.

JENKINS Janet, In the Spirit of Fluxus, Minneapolis, Minn. (Etats-Unis), Walker Art Center, 1993.

JOHNSON T., The Voice of the New Music, New York (Etats-Unis), Het Apollohuis, 1989.

KAPROW Allan, Assemblages, Environnements, Happenings, New York (Etats-Unis), H.N. Abrams, 1966.

KAPROW Allan, L’art et la vie confondus, Paris (France), Editions du Centre Pompidou, 1996 (Supplémentaires).

KARCZMAR Natan, Vidéo 6e : événement vidéo collectif et simultané, 8-9-10 janvier 1986. Paris (France), Ecole nationale des beaux-arts, 1986.

KHAN Douglas, Noise Water Meat : A History of Sound in the Arts, Cambridge, Mass. (Etats-Unis), MIT Press, 1999.

KIVY Peter, The Fine Art of Repetition : Essays in the Philosophy of Music, Cambridge (Royaume-Uni), Cambridge University Press, 1993.

KLONARIS Maria, THOMADAKI Katerina, Technologies et imaginaires, Art cinéma, art vidéo, art ordinateur, Paris (France), Editions Dis Voir, 1990.

Pour une écologie des médias : art, cinéma, vidéo, ordinateur / sous la dir. de Maria KLONARIS et Katerina THOMADAKI, Paris (France), ASTARTI, 1998.

Video Art : an Anthology / sous la dir. de Beryl KOROT, Mary LUCIER, Ira SCHNEIDER, New York (Etats-Unis) ; Londres (Royaume-Uni), Harcourt, Bace and Jovaniovitch, 1976.

KRUGER Barbara, TV Guides, A Collection of Thoughts about Television. New York (Etats-Unis), Kuklapolitan Press, 1985.

KULTERMAN Udo, Art, Events and Happenings, Londres (Royaume-Uni), Matthews, Miller and Dunbar, 1971.

Wie haltbar ist Videokunst ? = How durable is Video Art ? [colloque], Wolsburg (Allemagne), Kunstmuseum, 1997.

LANDOW George, Hypertext :the Convergence of Contemporary Critical Theory and Technology, Baltimore, Md. (Etats-Unis), Londres (Royaume-Uni), Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992.

LERNER Loren, Canadian film and video : a bibliography guide to the literature = Film et vidéo canadiens : bibliographie analytique sur le cinéma et la video, Toronto, Ont. (Canada) ; Buffalo, N.Y. (Etats-Unis) ; Londres (Royaume-Uni), University of Toronto Press, 1997.

LEVINSON Jerrold, L’art, la musique et l’histoire, Paris (France), Editions de l’Eclat, 1998.

LEVY Pierre, La machine univers : création, cognition et culture informatique, Paris (France), Editions La Découverte, 1987.

LEVY Pierre, Les technologies de l’intelligence : l’avenir de la pensée à l’ère informatique, Paris (France), Editions La Découverte, 1990.

LEVY Pierre, Qu’est-ce que le virtuel ? Paris (France), Editions La Découverte, 1995.

LEVY Pierre, Cyberculture, Paris (France), O. Jacob, 1997.

LEVY Pierre, Becoming virtual : reality in the digital age, Paris (France) ; Londres ; Glasgow (Royaume-Uni), HarperCollins, 1998.

LOVEJOY Margot, Postmodern Currents, Art and Artists in the age of electronic media, Londres (Royaume-Uni), UMI Research Press, 1989.

Double take / sous la dir. de Anja LUTZ, Horst LIBERA, Berlin (Allemagne), Shift, 2000.

MADESTRAND Bo, Till filmen, Göteborg (Suède), Konstmuseum, 1996.

La vidéo, entre art et communication : guide de l’étudiant en art / sous la dir. de Nathalie MAGNAN, Paris (France), Ecole nationale des beaux-arts, 1997.

MALSCH Friedemann, STRECKEL Dagmar, PERUCCHI-PETRI Ursula, Künstler-Videos, Entwicklung und Bedeutung, Zurich (Suisse), Kunsthaus Zürich, 1995.

MANOVICH Lev, The Language of New Media, Cambridge, Mass. (Etats-Unis), MIT Press, 2000.

MARION Ph., Contraintes temporelles et plasticité : publicité et vidéo-clip [conférence suivie de débats], Cerisy, Centre culturel International, Cerisy la Salle (France), 14-21.06. 2001.

MAZA Monique, Les installations vidéo, ” œuvres d’art “, Paris (France) ; Montréal, Québec (Canada), L’Harmattan, 1998 (Champs visuels).

McLUHAN Marshall, FIORE Quentin, The Medium is the Message, New York (Etats-Unis), Random House, 1967 ; Message et massage, Paris (France), J.-J. Pauvert, 1968.

MOLES Abraham, Art et ordinateur, Paris (France), Blusson, 1990.

MONET Dominique, Le multimédia, Paris (France), Flammarion, 1998 (Domino).

MORSE Margaret, BLUNCK Annika, INÁCIO Isabel, Hardware, software, artware : die Konvergenz von Kunst und Technologie = Confluence of art and technologie, Ostfildern (Allemagne), Cantz, 1997.

MOVIN Lars, CHRISTENSEN Torben, Art and Video in Europe : Electronic Undercurrents, Copenhagen (Danemark), Statens Museum for Kunst, 1996.

Circulating Film and Video Catalogue : vol. 2. New York (Etats-Unis), Museum of Modern Art, 1990.

NASH Michael, Vision after television : technocultural convergence, hypermedia and the new media arts field, Minneapolis, Minn. (Etats-Unis), University of Minnesota Press, 1996.

NELSON J., The Perfect-Machine, TV in the Nuclear Age, Between the Lines, Toronto, Ont. (Canada), 1988.

NYMAN Michael, Experimental Music : Cage and Beyond, New York (Etats-Unis), Schirmer Books, 1974.

PAIK Nam June, Du cheval à Christo et autres écrits, Bruxelles (Belgique) ; Hambourg (Allemagne) ; Paris (France), L. Hossmann, 1993.

PAIK Nam June, Niederschriften eines Kulturnomaden : Aphorismen, Briefe, Texte, Cologne (Allemagne), DuMont, 1992.

PAIK Nam June, Beuys vox 1961-86, Séoul (Corée), Won Gallery ; Hyundai Gallery, 1986.

PAIK Nam June, Art for 25 million people-Bonjour, Monsieur Orwell-Kunst und Satelliten in der Zukunft, Berlin (Allemagne), DAAD Galerie, 1984.

PAIK Nam June, Art and Satellite, Berlin (Allemagne), DAAD Galerie, 1984.

PAIK Nam June, HANGARDT John G., Nam June Paik : Mostly Video, Tokyo (Japon), Metropolitan Art Museum, 1984.

PAIK Nam June [préf.], Catherine Ikam : dispositif pour un parcours vidéo, Paris (France), Musée national d’art moderne, 1980.

PARFAIT Françoise, Vidéo : un art contemporain, Paris (France), Editions du Regard, 2001.

Vidéo / sous la dir. de René PAYANT, Montréal, Québec (Canada), Editions Artextes, 1986.

Critical issues in electronic media / sous la dir. de Simon PENY, Albany, N.Y. (Etats-Unis), State University of New York, 1995.

PERINCIOLI Cristina, RENTMEISTER Cillie, Computer und Kreativität : ein Kompendium für Computer-grafik, Animation, Musik und Video, Cologne (Allemagne), DuMont, 1990.

PERREE Rob, Into Video Art : the Caracteristics of a Medium = de karakterieken van een medium, Rotterdam ; Amsterdam (Pays-Bas), Con Rumore, 1988.

Künstler-Video : Entwicklung und Bedeutung : die Sammlung der Videobänder des Kunsthauses Zurich / sous la dir. de Ursula PERUCCHI-PETRI, Ostfildern-Ruit (Allemagne), Cantz, 1996.

PEZOLD Friederike, Kunst für das 21. Jahrhundert : Entwurf einer Gegenwelt = Art for the 21st century : Design of a counterworld = L’art pour le 21ème siècle : croquis d’un contremonde, Ostfildern (Allemagne), Cantz, 1995.

POPPER Frank, L’Art à l’âge électronique, Paris (France), Hazan, 1993.

POTTIER Marc, MOISDON Stéphanie, MOURAUD Tania, Walk on the Soho Side, Turin (Italie), Arte Fratelli Pozzo, 1997.

PREIKSCHAT Wolfgang, Video : Die Poesie der Neuen Medien, Bâle (Suisse), Belz, 1987.

PRICE Jonathan, Video-visions : a medium discovers itself, New York (Etats-Unis), New American Library, 1977.

QUEAU Philippe, Eloge de la simulation : de la vie des langages à la synthèse des images, Paris (France), Champ-Vallon, 1986.

QUEAU Philippe, Metaxu : Théorie de l’art intermédiaire, Seyssel (France), Champ-Vallon, Bry-sur-Marne (France), INA, 1989.

QUEAU Philippe, Le Virtuel : vertus et vertiges, Seyssel (France), Champ-Vallon ; Bry-sur-Marne (France), INA, 1993.

Resolution : contemporary video practices / sous la dir. de Michael RENOV et Erika SUDERBURG, Minneapolis, Minn. (Etats-Unis), University of Minnesota Press, 1996.

REYNOLDS Simon, Blissed out : the Rapture of Rock, Londres (Royaume-Uni), Serpent’s Tail, 1990.

REYNOLDS Simon, Energy Flash : A Journey through Rave Music and Dance Culture, Londres (Royaume-Uni), Picador, 1998 ; éd. américaine, Generation Ecstasy : Into the World of Techno and Rave Culture, Boston, Mass. (Etats-Unis), Little Brown, 1998.

ROSS Christine, Images de surface : l’art vidéo reconsidéré, Montréal, Québec (Canada), Artextes, 1996.

ROSS D., Artist’s Video, New York (Etats-Unis), 1973.

ROSSET Clément, Le réel : traité de l’idiotie, Paris (France), Editions de Minuit, 1977.

ROSSET Clément, Le réel et son double, Paris (France), Gallimard, 1984 (1ère éd.).

ROSSET Clément, Le réel, l’imaginaire et l’illusoire, Biarritz (France), Editions Distance, 2000.

RUSH Michael, New Media in Late 20th Century Art, Londres (Royaume-Uni), Thames and Hudson, 1999 (World of art).

RUSH Michael, Les nouveaux médias dans l’art, Paris (France), Thames and Hudson, 2000 (L’Univers de l’art ; 82).

RUSH Michael, L’art vidéo, Londres (Royaume-Uni), Thames and Hudson, 2003.

SAGERER Alexeij, ProT bringt Video, Film auf Video, Munich (Allemagne), Werkstatt, 1983.

SCHIMMEL Paul, Out of Actions : Between Performance and the Object 1949-1979, Los Angeles, Calif. (Etats-Unis), 1998.

SCHNEIDER Irmela, THOMSEN Christian, W. Hybridkultur : Medien, Netze, Künste, Cologne (Allemagne), Wienand, 1997.

SCHWARZBAUER Georg F., Video in Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf (Allemagne), Staatlische Kunstacademie, 1984.

SHAPIRO Peter, LEE Iara, Modulations : A History of Electronic Music : Throbbing Words on Sound, Amsterdam (Pays Bas), DAP ; New York (Etats-Unis), Caipirinha Prod., 2000.

Widerstände : Kunst, Cultural Studies, Neue Medien : Interviews und Aufsätze der Zeitschrift Springerin 1995-1999 / sous la dir. de SPRINGERIN, Hefte für Gegenwartskunst, Vienne (Autriche) ; Bolzano (Italie), Folio, 1999.

TAMINIAUX P., Modernisme et mythes de l’image, [conférence suivie de débats], Cerisy, Centre culturel International, Cerisy la Salle (France), 14-21.06.2001.

Petits écrans et démocratie : vidéo légère et télévision alternative au service du développement / sous la dir. de Nancy THEDE et Alain AMBROSI, Paris (France), Syros/FPH/GRET, 1992 (Ateliers du développement).

THÉLY Nicolas, Vu à la webcam : essai sur la web-intimité, Dijon (France), Les Presses du réel, 2002 (Documents sur l’art).

TOOP David, Ocean of Sound, Aether Talk, Ambient Sound and Imaginary Worlds, Londres (Royaume-Uni), Serpent’s Tail, 1995 ; Ocean of Sound, Ambient music, mondes imaginaire et voix de l’éther, Paris (France), Kargo-L’Eclat, 2000.

TOOP David, The Rap Attack : African Jive to New York Hip Hop, Londres (Royaume-Uni), Pluto Press, 1984.

TOOP David, The Rap Attak 2 : African Rap to Global Hip Hop, Londres (Royaume-Uni), Serpent’s Tail, 1991.

TOOP David, The Rap Attak 3 : African Rap to Global Hip Hop, Londres (Royaume-Uni), Serpent’s Tail, 2000

TOUCHARD Jean-Baptiste, Images numériques, Paris (France), Cedic Vifi International ; Nathan, 1987.

Video by artists 2 / Elke TOWN, Toronto, Ont. (Canada), Art Metropole, 1986.

TRESCHER Stephan, Light boxes : Leuchtkastenkunst, Nuremberg (Allemagne), Institut für moderne Kunst, 1999.

ULMER Gregory, Teletheory : Grammatology in the Age of Video, New York (Etats-Unis), Routledge, 1989.

VAILLANT Alexis, PARFAIT Françoise, JANCOVIC Nikola, Les nouvelles images en 2001 : tome 1 : télévision, vidéo, internet, Paris (France), AFAA ; Ministère des affaires étrangères, 2001 (Chroniques de l’AFAA ; 29).

VALENTINI Valentina, Dirottamenti : Calle, Cohen, DV8, Pellizzari, Sellars, Milan (Italie), Comune di Milano, 1997.

La camera astratta : tre spettacoli tra teatro e video / sous la dir. de Valentina VALENTINI, Milan (Italie), Ubulibri, 1988.

Allo specchio / sous la dir. de Valentina VALENTINI, Rome (Italie), Lithos, 1998.

Il video a venire / sous la dir. de Valentina VALENTINI, Rome (Italie), Rubbettino, 1999.

Vidéo et après : la collection vidéo du Musée national d’art moderne / sous la dir. de Christine VAN ASSCHE, Paris (France), Editions du Centre Pompidou, 1992.

Actualité du virtuel, revue virtuelle sur CD-Rom / sous la dir. de Christine VAN ASSCHE, Paris (France), Editions du Centre Pompidou, 1996.

Art after Modernism : Rethinking Representation / sous la dir. de B. WALLIS, New York (Etats-Unis), New Museum of Contemporary Art, 1984.

The artist’s body / Tracey WARR avec la collab. d’Amelia JONES, Londres (Royaume-Uni), Phaidon, 2000.

WEIBEL Peter, On Justifying the Hypothetical Nature of Art and the Non-identicality within the Object World, Cologne (Allemagne), T. Grunert, 1992.

Les Chemins du virtuel : simulation informatique et création industrielle / sous la dir. de J.L.

WEISSBERG, Paris (France), Editions du Centre Pompidou, 1989.

WYWER John, The Moving Image : An International History Film : Television and Video, Oxford (Royaume-Uni), British Film Institute-Basil Backwell, 1990.

YOUNGBLOOD Gene, Expanded Cinema, New York (Etats-Unis), Dutton, 1969.

Electronic Arts Intermix : video / sous la dir. de Lori ZIPPAY, New York (Etats-Unis), Electronic Arts Intermix, 1991.

Ouvrages généraux

ARDENNE Paul, Un art contextuel : art urbain, en situation, d’intervention, de participation, Paris (France), Flammarion, 2002.

ADORNO Theodor Wiesengrund, Théorie esthétique, Paris (France), Klincksieck, 1974.

ADORNO Theodor Wiesengrund, Philosophie der neuen Musik, Tübingen (Allemagne), P. Siebeck, 1949 ; Philosophie de la nouvelle musique, Paris, Gallimard, 1962 [dernière éd. 1995].

BAUDRILLARD Jean, Simulacres et simulation, Paris (France), Galilée, 1979.

BAUDRILLARD Jean, Les stratégies fatales, Paris (France), Grasset, 1983.

BENJAMIN Walter, L’homme, le langage et la culture, Paris (France), Gonthier, 1974.

BENJAMIN Walter, Essais II, 1935-1940, Paris (France), Denoël / Gonthier, 1983.

From Work to Text = Da obra ao texto / sous la dir. de Jürgen BOCK, Centro cultural de Belém, Lisbonne (Portugal), 2002.

BOISSIER Jean-Louis, La relation comme forme. L’interactivité en art, Genève (Suisse), Editions MAMCO, 2004.

BOLTER Jay David, GRUSIN Richard, Remediation : Understanding New Media, Cambridge, Mass. (Etats-Unis), MIT Press, 1999.

BOUCHINDHOMME Christian, ROCHLITZ Rainer, L’Art sans compas : redéfinitions de l’esthétique, Paris (France), Editions Le Cerf, 1992.

BOURDIEU Pierre, Sur la télévision, Paris (France), Liber Editions, 1998.

BOURRIAUD Nicolas, Esthéthique relationnelle, Dijon (France), Les Presses du réel, 1998.

BOURRIAUD Nicolas, Formes de vie : l’art moderne et l’invention de soi : essai, Paris (France), Denoël, 1999.

BÜRGER Peter, Theory of the Avant-Garde, Minneapolis, Minn. (Etats-Unis), University of Minnesota Press, 1992.

BÜRGER Peter, The Decline of modernism, Philadelphie, Pa. (Etats-Unis), University Park Press, 1992.

DAMISH Hubert, Théorie du nuage, Pour une théorie de la peinture, Paris (France), Editions du Seuil, 1972.

DEBORD Guy, La société du spectacle, Paris (France), Buchet-Chastel, 1967 [1ère éd.].

DEBORD Guy, Commentaires sur la société du spectacle, Paris (France), G. Lebovici, 1988.

DELEUZE Gilles, Logique du sens, Paris (France), Editions de Minuit, 1969.

DELEUZE Gilles, Cinéma 1. L’image-mouvement, Paris (France), Editions de Minuit, 1983.

DELEUZE Gilles, Cinéma 2. L’image-temps, Paris (France), Editions de Minuit, 1985.

DELEUZE Gilles, Le pli, Leibniz et le baroque, Paris (France), Editions de Minuit, 1988.

DELEUZE Gilles, GUATTARI Félix, Qu’est-ce que la philosophie ? Paris (France), Editions de Minuit, 1991.

DERRIDA Jacques, L’écriture et la différence, Paris (France), Editions du Seuil, 1967.

DERRIDA Jacques, La voix et le phénomène, Paris (France), Editions PUF, 1967.

ECO Umberto, L’oeuvre ouverte, Paris (France), Editions du Seuil, 1965.

ECO Umberto, La structure absente : introduction à la recherche sémiotique, Paris (France), Mercure de France, 1972.

FOSTER Hal, The Anti-Aesthetic, Essays on Postmodern Culture, Seattle, Wash. (Etats-Unis), Bay Press, 1983.

FOSTER Hal, Recodings, Art, Spectacles, Cultural Politics, Washington, D.C. (Etats-Unis), Bay Press, 1985.

FOSTER Hal, Discussions in Contemporary Culture, Seattle, Wash. (Etats-Unis), Bay Press, 1987.

FOUCAULT Michel, Surveiller et punir : naissance de la prison, Paris (France), Gallimard, 1975.

FOUCAULT Michel, Les mots et les choses, Paris (France), Gallimard, 1976.

GODARD Jean-Luc, Introduction à une véritable histoire du cinéma, Paris (France), Editions Albatros, 1980.

GRAHAM Gordon, The Internet : a Philosophical Enquiry, Londres (Royaume-Uni), Routledge, 1999.

HOFSTADTER Douglas, Gödel, Escher, Bach : les brins d’une guirlande éternelle, Paris (France), Inter Editions, 1985.

JAMESON Frederic, Postmodernism or the cultural logic of the late capitalism, Durham (Royaume-Uni), Duke University Press, 1991.

JAMESON Frederic, The Anti-Aesthetic, Washington, D.C. (Etats-Unis), Hal Foster, 1983.

KRAUSS Rosalind, Passages in Modern Sculpture, Londres (Royaume-Uni), Thames and Hudson, 1977 ; Passages : une histoire de la sculpture de Rodin à Smithson, Paris (France), Macula, 1997.

KRAUSS Rosalind, The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths, Cambridge, Mass. (Etats-Unis), Cambridge MIT Press, 1985 ; L’originalité de l’avant-garde et autres mythes modernistes, Paris (France), Macula, 1993.

LACAN Jacques, Ecrits I, Paris (France), Editions du Seuil, 1971.

LUNENFELD Peter, The Digital Dialectic, new essays on new medias, Cambridge, Mass. (Etats-Unis), MIT Press, 1999.

LYOTARD Jean-François, Discours, figure, Paris (France), Klincksieck, 1978.

LYOTARD Jean-François, La condition postmoderne, Paris (France), Editions de Minuit, 1979.

McLUHAN Marshall, Pour comprendre les médias, Paris (France), Editions du Seuil, 1968.

McLUHAN Marshall, La galaxie Gutenberg, Paris (France), Gallimard, 1977.

MARCUS Greil, Lipstick traces : a secret history of the 20th century, Cambridge, Mass. (Etats-Unis), Harvard University Press, 1989 ; Lipstick traces : une histoire secrète du 20e siècle, Paris (France), Allia, 1998.

MERLEAU-PONTY Maurice, Le Visible et l’invisible, Paris (France), Gallimard, 1964.

MERLEAU-PONTY Maurice, Le primat de la perception et ses conséquences philosophiques, précédé de Projet de travail sur la nature de la perception, 1933 ; La nature de la perception, 1934, Lagrasse (France), Verdier, 1996.

PANOFSKY Edwin, La perspective comme forme symbolique, Paris (France), Editions de Minuit, 1975.

POSCHARDT Ulf, Dj Culture, Hambourg (Allemagne), Rogner und Bernhard bei Zweitausendeins, 1995 ; Dj Culture, Londres (Royaume-Uni), Quartet Books Limited, 1998 ; Dj Culture, Paris (France), Kargo, 2001.

RANCIÈRE Jacques, Le partage du sensible : esthétique et politique, Paris (France), Editions La Fabrique, 2000.

RANCIÈRE Jacques, L’inconscient esthétique, Paris (France), Editions Galilée, 2001.

RANCIÈRE Jacques, La fable cinématographique, Paris (France), Editions du Seuil, 2001 (La Librairie du 20e siècle).

ROCHLITZ Rainer, Théories esthétiques après Adorno, Arles (France), Actes Sud, 1990.

SERRES Michel, La communication, Hermès 2, Paris (France), Editions de Minuit, 1974.

SHUSTERMAN Richard, Pragmatist Aesthetic : Living Beauty, Rethinking Art, Oxford, Blackwell, 1992. L’Art à l’état vif : la pensée pragmatiste et l’esthétique populaire, Paris (France), Editions de Minuit, 1992 (Le Sens commun).

SONTAG Susan, La photographie, Paris (France), Editions du Seuil, 1979.

SONTAG Susan, A Susan Sontag Reader, New York (Etats-Unis), Vintage, 1982.

SZENDY Peter, Ecoute, une histoire de nos oreilles, Paris (France), Editions de Minuit, 2001.

THOM René, Paraboles et catastrophes, Paris (France), Flammarion, 1983.

VATTIMO Gianni, La fin de la modernité, Nihilisme et herméneutique dans le Tractatus logico-philosophicus, Paris (France), Gallimard, 1961.

VATTIMO Gianni, La culture postmoderne, Paris (France), Editions du Seuil, 1987.

VATTIMO Gianni, La société transparente, Paris (France), D. de Brouwer, 1990.

VATTIMO Gianni, Ethique de l’interprétation, Paris (France), Editions La Découverte, 1991.

VIRILIO Paul, Vitesse et Politique, Paris (France), Editions Galilée, 1977.

VIRILIO Paul, Esthétique de la disparition, Paris (France), Balland, 1980.

VIRILIO Paul, L’Espace critique, Paris (France), C. Bourgeois, 1984.

VIRILIO Paul, L’Horizon négatif, Paris (France), C. Bourgeois, 1984.

VIRILIO Paul, L’Inertie polaire, Paris (France), C. Bourgeois, 1984.

VIRILIO Paul, Guerre et cinéma 1 : logistique de la perception, Paris (France), Editions de l’Etoile, 1986.

VIRILIO Paul, L’Art du moteur, Paris (France), Editions Galilée, 1993.

VIRILIO Paul, Cybermonde, la politique du pire, Paris (France), Editions Textuel, 1996.

VIRILIO Paul, La Machine de vision, Paris (France), Editions Galilée, 1998.

WILLIAM Gilda, BAUMAN Zygmunt, GILLICK Liam, GROSZ Elizabeth, Fresh Cream : art contemporain et culture : 10 conservateurs, 10 auteurs, 100 artistes, Paris (France), Phaidon, 2000.

WITTGENSTEIN Ludwig, Recherches philosophiques, Paris (France), Gallimard, 1970.

WITTGENSTEIN Ludwig, Leçons et conversations : conférences sur l’éthique, Paris (France), Gallimard, 1971.

Catalogues d’expositions

010101. Art in Technological Times / John S. WEBER, Aaron BETSKY, Benjamin WEIL, MoMA, San Francisco, Calif. (Etats-Unis), 03.03.-08.07.2000.

About Time : Video, Performance and Installation by 21 Women Artists, Institute of Contemporary Art, Londres (Royaume-Uni), 1980.

A Forest of Signs : Art in the Crisis of Representation / sous la dir. de Catherine GUDIS, Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, Calif. (Etats-Unis), 07.05.-13.08.1989.

Americal Film and Video / Peggy AHWESH, Lawrence ANDREWS, Stan BRAKHAGE, Whitney Biennial : Electronic Undercurrents, Statens museum for kunst, Copenhague (Danemark), 07.09.-30.11.1996.

Action, on tourne = Action, we ‘re filming / sous la dir. de Laurence GATEAU, Villa Arson, Nice (France), 2000-2001.

Acting Out : the Body in Video then and now / org. par Julia BUNNAGE, Clarrie RUDRUM, Annushka SHANI, Alessandro VINCENTELLI, Victoria WALSH, Henry Moore Gallery, Royal College of Art, Londres (Royaume-Uni), 22.02.-13.03.1994.

American Documentary Video : Subject to change : a Video Exhibition / Deirdre BOYLE, Museum of Modern Art, New York (Etats-Unis), 17.11.1988-10.01.1989.

American Landscape Video / William D. JUDSON, Electronic Grove, Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, Pa. (Etats-Unis), 1988.

Art and Electronics / Uwe NITSCHKE et Wulf HERZOGENRATH, Pao Sui Loong Gallery ; Pao Yue Kong Galleries ; Hong Kong Art Centre, Hong Kong (Hong Kong), 16.02.-05.03.1995.

Art and Film since 1945 / Kerry BROUGHER, Jonathan CRARY, Russell FERGUSON, Hall of Mirrors, Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, Calif. (Etats-Unis), 1996.

Art and Technology / sous la dir. de Atsuhiko SHIMA et Masakatsu OTA, Museum of Modern Art, Toyama (Japon), 01.07.-04.09.1983.

Art and Video in Europe : Electronic Undercurrents / Lars MOVIN, Torben CHRISTENSEN, Soren ANDREASEN, Statens museum for kunst, Copenhague (Danemark), 07.09-30.11.1996.

L’Art au corps, le corps exposé de Man Ray à nos jours / Catherine MILLET et François PLUCHART, MAC, Musées de Marseille, Marseille (France), 06.07.-15.10.1996.

Art et ordinateur, vidéo et ordinateur /Anne-Marie DUGUET, Maison de la Culture, La Rochelle (France), 24.06.-31.08.1983.

The Arts for Television / sous la dir. de Kathy Rae HUFFMAN et Dorine MIGNOT, Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, Calif. (Etats-Unis) ; Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam (Pays-Bas), 1987.

Art >Music : Rock, Pop, Techno / Sue CRAMER, Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney (Australie), 21.03.-24.06.2001.

Art vidéo : rétrospectives et perspectives / sous la dir. de Laurent BUSINE, Palais des beaux-arts, Charleroi (Belgique), 1983.

Art vidéo : confrontation 74 / Suzanne PAGÉ, Claudine EIZYKMAN, Yann PAVIE, Donald A. FORESTA, ARC, Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, Paris (France), 08.11.-8.12.1974.

L’art vidéo depuis 1976 en République Fédérale d’Allemagne : une sélection / Helmut FRIEDEL et Wolfgang PREIKSCHAT, Goethe Institut, Munich (Allemagne), 1986.

Art vidéo-vidéo art / Don FORESTA et Dominique BELLOIR, Le nouveau musée, Institut d’art contemporain, Villeurbanne (France), 19.02.-28.03.1980.

L’arte elettronica : metamorfosi e metafore / sous la dir. de Silvia BORDINI, Palazzo dei Diamanti, Ferrare (Italie), 24.06.-02.09.2001.

Artronica : videosculture e installazioni multimedia / sous la dir. de Anna D’ELIA, Santa Scolastica, Bari (Italie), 1987.

Being and Time : the Emergence of Video Projection / sous la dir. de Marc MAYER, Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, N.Y. (Etats-Unis), 1996.

3e Biennale de Lyon : installation, cinéma, vidéo, informatique, Musée d’art contemporain ; Cité internationale ; Palais des Congrès, Lyon (France), 1995.

11e Biennale de Paris, Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, Paris (France), 1980.

12e Biennale de Paris, Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, Paris (France), 1982.

Blam ! The Explosion of Pop, Minimalism and Performance, 1958-1964 / sous la dir. de Barbara HASKELL, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (Etats-Unis), 1984.

Boomerang / sous la dir. de Susan HINNUM, Malene LANDGREEN, Sanne KOFOD OLSEN, Nicolaj-Copenhagen Contemporary Art Center, Copenhague (Danemark), 21.02.-19.04.1998.

Campo video : nuova videoarte slovena = Slovenian videoart / sous la dir. de Aurora FONDA, Venise (Italie), 06-31.12.1999.

CH’ 70-’ 80 : schweizer Kunst ‘70-’80 / préf. de Martin KUNZ, Kunstmuseum, Lucerne (Suisse), 1981.

Cinema Cinema : Contemporary Art and the Cinematic Experience / Jaap GULDEMOND, Jean-Christophe ROYOUX, Stedelijk Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven (Pays-Bas), 1999.

Correnti magnetiche : immagini virtuali e installationi interattive / sous la dir. de Maria Grazia MATTEI, Centro espositivo della Rocca Paolina, Pérouse (Italie), 11-25.05.1996.

La création vidéo en Belgique 1970-1990 / Philippe DUBOIS et Marc-Emmanuel MÉLON, Musée d’art moderne de la Ville de Paris, Paris (France), 1991.

Crossings : Kunst zum Hören und Sehen / sous la dir. de Cathrin PICHLER et Edek BARTZ, Kunsthalle, Vienne, (Autriche), 29.05.-13.09.1998.

De l’instabilité / sous la dir. de Jean-Michel FORAY et Martine BOUR, Centre national des arts plastiques, Paris (France), 16.11.-10.12.1989.

De la création vidéo française / sous la dir. de Stephen SARRAZIN, Institut français, Bucarest (Roumanie), 15-21.11.1991.

Digital Visions, Computer and Art, Everson Museum of Art, Syracuse, N.Y. (Etats-Unis), 1987.

Dirottamenti / sous la dir. de Valentina VALENTINI, Fondazione Mudima, Milan (Italie), 1996.

Ecstatic Memory : a Year-Long Series of 5 Video Programs = Souvenir sublime : une série de 5 programmes vidéo / préf. de Peggy GALE, Musée des beaux-arts de l’Ontario, Toronto, Ont. (Canada), 09.01.1999-02.01.2000.

Electra : l’électricité et l’électronique dans l’art au 20e siècle = Electra : Electricity and Electronics in the Art of the 20th Century / textes de Marie-Odile BRIOT, Jean VERMEIL, Sylvain LECOMBRE, Jean-Louis BOISSIER, Dominique BELLOIR, Edmond COUCHOT, Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, Paris (France), 1983.

Elettroshock : 30 anni di video in Italia 1971-2001 / sous la dir. de Bruno DI MARINO et Lara NICOLI, Museo Laboratorio di arte contemporanea, Rome (Italie) 21-27.05.2001.

En el lado de la televisión : projecte de Jorge Luis Marzo, Espai d’art contemporani de Castelló, Castelló (Espagne), 04.10.-01.12.2002.

L’Epoque, la mode, la morale, la passion / sous la dir. de Bernard BLISTÈNE, Catherine DAVID, Alfred PACQUEMENT, Musée national d’art moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris (France), 21.05.-17.08.1987.

L’ère binaire : nouvelles interactions / sous la dir. de Charles HIRSCH et Michel BAUDSON, Musée communal, Ixelles (Belgique), 4.09.-29.11.1992.

Escape-Space : Raumkonzepte mit Fotografien, Zeichnungen, Modellen und Video / sous la dir. de Ursula FROHNE et Christian KATTI, Ursula Blickle Stiftung, Kraichtal (Allemagne), 2000.

Ex oriente lux / sous la dir. de Calin DAN, Sala Dalles, Bucarest (Roumanie), 24.11.-20.12.1993.

FremdKörper = Corps étranger = Foreign Body / texte de Theodora VISCHER, Museum für Gegenwartskunst, Bâle (Suisse), 01.06.-29.09.1996.

From TV to Video e dal video alla TV : Nuovo tendenze del video nordamericano, L’immagine elettronica, Bologne (Italie), 1984.

Geschichten des Augenblicks : über Narration und Langsamkeit = Moments in time : on narration and slowness / sous la dir. de Susanne GAENSHEIMER et Helmut FRIEDEL, Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus, Munich (Alemagne), 1999.

Heart of darkness / sous la dir. de Marianne BROUWER, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo (Pays-Bas), 18.12.-1994-27.03.1995.

: Video als weibliches Terrain = Video as a Female Terrain / sous la dir. de Stella ROLLIG, Landesmuseum Joanneum, Graz (Autriche), 28.10.-10.12.2000.

Herz von Europa = Heart of Europa / sous la dir. de Ilse GASSINGER, Inge GRAF, Walter ZYX, Infermental 9, Vienne (Autriche), 1989.

Het lumineuze beeld = The luminous image, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam (Pays-Bas), 14.09.-28.10.1984.

Hors-Limites, l’art et la vie 1952-1994 / sous la dir. de Jean de LOISY, Musée national d’art moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris (France), 09.11.1994-23.01.1995.

Ich und die anderen : Fotografien und Videoarbeiten / sous la dir. de Ulrich POHLMANN, Ursula Blickle Stiftung, Kraichtal (Allemagne), 14.11-12.12.1999 ; Fotomuseum, Munich (Allemagne), 16.03.-07.05.2000.

Image on the Run : Dutch Video Art of the 80’s / textes de Rob PERRÉE et Sebastian LOPEZ, Amsterdam (Pays-Bas), 1985.

Image World : Art and Media Culture / Marvin HEIFERMAN, Lisa PHILLIPS, John G. HANHARDT, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (Etats-Unis), 08.11.-18.1989-18.02.1990.

Imágenes del video 1989 : ayudas para jóvenes creadores 1988, Instituto de la juventud, Madrid (Espagne), 24.05.-17.06.1989.

Images en scène : installations vidéo et cinéma, spectacle, danse, image / sous la dir. de Anne-Marie CORNU, Palais de Tokyo, Paris (France), juin 1993. Art 3000, Jouy-en-Josas (France), 1993.

Imatges en moviment = Moving Image : Electronic Art / Zentrum für Kunst und Medientechnologie Karlsruhe, Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelone (Espagne), 1992, Munich (Allemagne), Oktagon, 1992.

L’immagine elettronica : Eu-video ’85 : tendenze europee a confronto, Palazzo dei Congressi, Bologne (Italie), 16-19.02.1985.

L’immaginario technico : rassegna internazionale, Museo del Sannio, Bénévent (Italie), 26.03.-14.04.1984.

Les Immatériaux / Yannick COURTEL, Nathalie HEINICH, Jean-François LYOTARD, Charles PERRATON, Centre de création industrielle, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris (France), 28.03.-15.07.1985.

Imperfect innocence : the Debra and Dennis Scholl collection / Nancy SPECTOR, James RONDEAU, Michael RUSH, Contemporary Museum, Baltimore, Md. (Etats-Unis), 11.01.-11.03.2003 ; Palm Beach Institute of Contemporary Art, Lake Worth, Fla. (Etats-Unis), 12.04.-15.06.2003.

Impressions danse, Intermédia, Paris (France), 1988.

In video / sous la dir. de Sandra LISCHI et Felice PESOLI, Centro internazionale di Brera, Milan (Italie), 22-25.11.1990.

Das innere befinden : das Bild des Menschen in der Videokunst der 90er Jahre = The inner state : the image of man in the video art of the 1990s / Christiane MEYER-STOLL, Hannelore PAFLIK-HUBER, Annette PHILIP, Kunstmuseum Liechtenstein, Vaduz (Liechtenstein), 2001.

Into the Light : the Projected Image in American Art 1964-1977 / sous la dir. de Chrissie ILES, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (Etats-Unis), 18.10.2001-06.01.2002.

Installations vidéo : en collaboration avec Video Art Plastique, Théâtre d’Hérouville (France), 26.11.-13.12.1988.

Iterations : the New Image / sous la dir. de Timothy DRUCKREY, International Center of Photography, New York (Etats-Unis), 1993-1994.

Junge Szene ’96 / Andreas SPIEGL et Doris ROTHAUER, Wiener Secession, Vienne (Autriche), 19.07.-15.09.1996.

Kunst und Technologie : elektronische Künste / sous la dir. de Philomene MAGERS, Bärbel MOSER, Petra UNNÜTZER, Wissenschaftszentrum, Bonn-Bad Godesberg (Allemagne), 12.12.1986-04.01.1987.

KünstlerInnen : 50 Positionen, zeitgenössischer internationaler Kunst : Videoportraits und Werke / sous la dir. de Edelbert KÖB, Kunsthaus, Bregenz (Autriche), 28.09.-30.11.1997.

La Imagen sublime, video de creación en España 1970-1987, Madrid (Espagne), 1987.

Laboratorio de Luz : PB 97-0335 : idea, imagen, universidad / Amparo CARBONELL, Salomé CUESTA, Maribel DOMÈNECH, Sala de exposiciones, Universidad politécnica, Valence (Espagne), 8-30.03.2001.

Lost in Sound 2 / sous la dir. de Manoel de OLIVEIRA, Centro galego de arte contemporánea, Saint-Jacques de Compostelle (Espagne), 02.12.1999-12.03.2000.

Le ludique / Marie FRASER, Musée du Québec, Québec (Canada), 27.09.-25.11.2001.

Magnetic North : Canadian Experimental Video / sous la dir. de Jenny LION, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, Minn. (Etats-Unis), octobre 2000 ; Plus In, Winnipeg, Man. (Canada), novembre 2000.

Memoria del video : 1 : La distanza della storia : vent’anni di eventi video in Italia raccolti da Luciano Giaccari / sous la dir. de Marco MENEGUZZO, Padiglione d’arte contemporanea, Milan (Italie), 15.12.1987-31.01.1988.

Mirades impúdiques : foto, video, film, websites / Rosa OLIVARES et Manuel DELGADO, Centre cultural de la Fundació La Caixa, Barcelone (Espagne), 13.04.-25.06.2000.

Monter-sampler : l’échantillonage généralisé / sous la dir. de Yann BEAUVAIS et Jean-Michel BOUHOURS, Paris (France), Editions du Centre Pompidou ; Scratch Projection, 2000 (Quinze x Vingt & Un : Cinéma musique).

Moving Pictures / sous la dir. de Lisa DENNISON et Nancy SPECTOR, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York (Etats-Unis), 28.06.2002-12.01.2003.

Múltiplas dimensões = Multiples dimensions / Eugeni BONET et Christine VAN ASSCHE, Centro cultural de Belém, Lisbonne (Portugal), 07.06.-31.07.1994.

Mutations de l’image : art cinéma, vidéo, ordinateur / sous la dir. de Maria KLONARIS et Katerina THOMADAKI, ASTARTI pour l’audiovisuel, Paris (France), 1994.

Nature is Perverse, Fylkingen ; Moderna Museet, Stockholm (Suède), 27-29.11.1998.

Net-Condition : Art and Global Media / sous la dir. de Peter WEIBEL et Timothy DRUCKREY, Steirischer Herbst, Graz (Autriche), 25.09.-24.10.1999.

New California Video : a Survey of Open Channel, 1985-89, Long Beach Museum of Art, Long Beach, Calif. (Etats-Unis), 1989.

New video : Japan : a video exhibition …, Museum of Modern Art, New York (Etats-Unis), 1985.

Nouvelles fictions dans la vidéo en France / Jean-Paul FARGIER, ARC, Musée d’art moderne de la Ville de Paris, Paris (France), 07.12.1985-09.02.1986.

Nouvelles tendances de la vidéo en France / sous la dir. de Christine VAN ASSCHE,

Musée national d’art moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris (France), 23.06.-30.10.1993.

Now See Hear ! Art, Language and Translation / sous la dir. de Ian WEDDE, City Art Gallery, Wellington (Nouvelle Zélande), 1990.

” On s’émerveille qu’une image arrive. Il pourrait ne rien y avoir “, Ecole régionale des beaux-arts Georges Pompidou, Dunkerque, (France), juin 1986.

Outer Space : 8 Photo and Video Installations / sous la dir. de Alexandra NOBLE, Newcastle upon Tyne, Laing Art Gallery, 1991 ; Hull, Ferens Art Gallery, 1991-1992 ; Londres, Camden Arts Centre, 1992 ; Bristol, Arnolfini Gallery, 1992. Londres (Royaume-Uni), South Bank Centre, 1991.

Passages de l’image / sous la dir. de Raymond BELLOUR, Catherine DAVID, Christine VAN ASSCHE, Musée national d’art moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris (France) ; Fundación Caixa de Pensiones, Barcelone (Espagne) ; Wexner Center for the Arts, Columbus, Ohio (Etats-Unis) ; Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, Calif. (Etats-Unis), 1990-1991.

Performance Art and Video Installation, Tate Gallery, Londres (Royaume-Uni), 16.09.-06.10.1985.

The Pleasure Machine : Recent American Video / Dean SOBEL, Milwaukee Art Museum, Milwaukee, Wis. (Etats-Unis), 14.06.-18.08.1991.

Points de vue, images d’Europe / sous la dir. de Christine VAN ASSCHE, Musée national d’art moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris (France), 14.12.1994-30.03.1995.

Positionen junger Kunst und Kultur : : im Rahmen von ” Das Neue Berlin “ / sous la dir. de Gisela SCHÖNE, Akademie der Künste, Berlin (Allemagne), 23.05.1999-01.01.2000.

Projections, les transports de l’image / Jacques AUMONT, Yann BEAUVAIS, Raymond BELLOUR, Le Fresnoy, Studio national des arts contemporains, Tourcoing (France), novembre 1997-janvier 1998.

Regards projetés : art vidéo dans les Balkans = Projected visions : video art in the Balkans / Marina GRZINIC, Zoran ERIC, Zoran PETROVSKI, Strasbourg (France), Musée d’art moderne et contemporain, 2001 ; Ecole supérieure des arts décoratifs, 2001.

Re-Play : Anfänge internationaler Medienkunst in Österreich / sous la dir. de Sabine BREITWIESER, Generali Foundation, Vienne (Autriche), 12.05.-06.08.2000.

Remembrances of Things Past : Collected Writings and Exhibition Catalog / sous. la dir. de Lane RELYEA et Connie FITZSIMONS, Long Beach Museum of Art, Long Beach, Calif. (Etats-Unis), 23.11.1986-18.01.1987.

Le repubbliche dell’arte : Schweiz = Suisse = Svizzera = Svizra / Daria FILARDO et Sergio RISALITI, Palazzo delle Papesse, Centro arte contemporanea, Sienne (Italie), 1999.

Le repubbliche dell’arte : Art and Artists from Israel and Palestina / sous la dir. de Emidio DIODATO et Asher SALAH, Sienne (Italie), Palazzo delle Papesse, Centro arte contemporanea, 2000.

Resolution, a Critique of Video Art, Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions, Los Angeles, Calif. (Etats-Unis), 1986.

Revision, Art Programmes of European Television Stations / sous la dir. de Dorine MIGNOT, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam (Pays-Bas), 1987.

Salade liégeoise : une rétrospective de dix ans de production de la vidéo de Liège = Ten years of video production from Liège / C. DERCON, P. DUBOIS, R. KALISZ, Internationaal Cultureel Centrum, Anvers (Belgique), 27.02.-17.04.1985.

Sans titre : contemporary photography and video from France / sous la dir. de Mary Evelynn SORRELL, International Contemporary Art Production, Houston, Tex. (Etats-Unis), 1985.

Scream and scream again : film in art / Chrissie ILES, Museum of Modern Art, Oxford (Royaume-Uni), 14.07.-27.10.1996.

The Second Link, Viewpoints on Video in the Eighties, Walter Phillips Gallery, Banff Center School of Fine Arts, Banff, Alta. (Canada), 1983.

Segnali d’opera : arte e digitale in Italia per l’aggiornamento di un museo : 19 premio nazionale arti visive, Civica galleria d’arte moderna, Gallarate (Italie), 19 octobre-23 novembre 1997.

Señales de vídeo : aspectos de la videocreación española de los ultimos años, Madrid ; Las Palmas de Grande Canarie ; Pamplune ; Palma de Majorque (Espagne), 1995-1996.

Signs of the Times : a Decade of Video, Film and Slide-Tape Installations in Britain, 1980-1990 / sous la dir. de Chrissie ILES, Museum of Modern Art, Oxford (Royaume-Uni), 1990.

Signs of the Times / sous la dir. de Chrissie ILES, La Ferme du Buisson, Centre d’art contemporain de Marne-la-Vallée, Noisiel (France), 26.11.1993-13.02.1994.

Sonic Boom, Hayward Gallery, Londres (Royaume-Uni), 27.04.-18.06.2000.

Sonic Process : une nouvelle géographie des sons /sous la dir. de Christine VAN ASSCHE, Museu d’art contemporani, Barcelone (Espagne), 04.05.-30.07.2002 ; Musée national d’art moderne, Paris (France), 16.10.2002-06.01.2003.

Space Odysseys : Sensation and Immersion / sous la dir. de Victoria LYNN, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney (Australie), 18.08.-14.10.2001 ; Australian Centre for the Moving Image, Melbourne (Australie), 03-04.2002.

Spellbound : Art and Film / Ian CHRISTIE et Philip DODD, Hayward Gallery, Londres (Royaume-Uni), 1996.

Sound and vision. Musikvideo und Filmkunst : Ausstellung Retrospektive / sous la dir. de Herbert GEHR, Deutsches Filmmuseum, Francfort sur le Main (Allemagne), avec la collaboration de Long Beach Museum of Art, 16.12.1993-03.04.1994.

Sounds and Files, Künstlerhaus, Vienne (Autriche), 10.03.-16.04.2000.

Sound Art-Sound as Media / Minoru HATANAKA et Rob YOUNG, NTT Inter Communication Center (ICC), Tokyo (Japon), 28.01.-12.03.2000.

Studio Azzurro / Andrea LISSONI, Palazzo delle Papesse, Centro arte contemporanea, Sienne (Italie), 22.06.-25.08.2002.

Subverting Television : a Three Part Programme of British Video Art, Arts Council of Great Britain, Londres (Royaume-Uni), 1986.

Schweizer Videokunst, Kunsthaus, Langenthal (Suisse), 1994.

Swiss video, Musée des beaux-arts, Lausanne (Suisse), 09.1978.

Technopop in Wonderland, Musée d’art moderne de la Ville de Paris, Paris (France), 06.05.-12.06.1983.

Tele-Journeys / sous la dir. de Joan JONAS et Jane FARVER, List Visual Arts Center, Cambridge, Mass. (Etats-Unis), 2002.

Télé-visions de l’Europe, Bibliothèque publique d’information, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris (France), Réunion des musées nationaux ; Editions du Centre Pompidou ; La Sept, 1990.

Transit : 60 artistes nés après 60 : œuvres du Fonds national d’art contemporain, Ecole nationale supérieure des beaux-arts, Paris (France), 16.09.-02.11.1997 ; Caisse des dépôts et consignations, Paris (France), 16-28.09.1997.

TV as a Creative Medium, Howard Wise Gallery, New York (Etats-Unis), 1969.

UVS-Videosampler = VIS-Vidéosampler = VIS-Videosampler : Unabhängiges Video Schweiz 1987 = Vidéo Indépendante Suisse 1987 = Video Indipendente Svizzera 1987, Lucerne (Suisse), 1987.

Video der 80er Jahre, Neue Galerie am Landesmuseum Joanneum, Graz (Autriche), 19.09.-11.10.1987.

Video Skulptur, Retrospektiv und Aktuell 1963-1989, Kölnischer Kunstverein ; Kunststation St. Peter ; Belgisches Haus ; Kunsthalle, Cologne (Allemagne), DuMont, 1989.

Video, Lijnbaancentrum, Rotterdam (Pays Bas), 09.02.-12.03.1973.

Video, europäische Videotheken / Helmut FRIEDEL, René COEHLO, Wies SMAIS, Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus, Munich (Allemagne), 20.10.-01.11.1981.

Vidéo topiques : / Patrick JAVAULT, Georges HECK, Maurizio LAZZARATO, Strasbourg (France), Musée d’art moderne et contemporain, 18.10.2002-02.02.2003.

Video : Towards Defining an Aesthetic / David HALL et Tamara KRIKORIAN, Third Eye Centre, Glasgow (Royaume-Uni), 16-21 mars 1976.

Video about video : Four French Artists : P.-A. Gette, Ph. Guerrier, Thierry Kuntzel, Ph. Oudard, University Art Museum, Berkeley, Calif. (Etats-Unis), 10.1980.

Video Art 4 : Contemporary Israeli Artists / Richard FLANTZ, Tel Aviv Museum of Art, Tel Aviv (Israël), 14.04.-10.06.2000.

Videoarte a Palazzo dei Diamanti 1973-1979, Foyer della Camera di Commercio, Turin (Italie) avril 1980.

Video arte internacional / Jorge GLUSBERG et Laura BUCCELLATO, Buenos Aires (Argentine) 1990, Museo nacional de bellas artes, Buenos Aires (Argentine), 1990.

Vidéo Cube, FIAC 2001, Pavillon du Parc, Paris (France), 10-15.10.2001.

Vidéo Cube, FIAC 2002, Pavillon du Parc, Paris (France), 24-28.10.2002.

Video cult/ures : multimediale Installationen der 90er Jahre / sous la dir. de Ursula FROHNE, Museum für Neue Kunst-Zentrum für Kunst und Medientechnologie, Karlsruhe (Allemagne) 1999.

Video de artista e televisão : a televisão vista por artistas de video, Museu de arte contemporanea, São Paulo (Brésil), 1986.

Videodreams, zwischen Cinematischem und Theatralischem = Videodreams, between the cinematic and the theatrical / éd. par Peter PAKESCH, Kunsthaus Graz am Landesmuseum Joanneum, Graz (Autriche), 15.05.-19.09.2004 ; Cologne (Allemagne), W. König, 2004.

Vidéo et multimédia / Soon-Gui KIM et Daniel CHARLES, Centre de la Vieille Charité ; Institut méditerranéen de recherche et de création, Marseille (France), 25.06.-10.07.1986.

Video-film et audio-visuel, Musée Sart Tilman, Liège (Belgique), 15.10.-15.11.1977.

Video International, Kunstmuseum, Aarhus (Danemark), 10-22 février 1976.

Video from Tokyo to Fukui and Kyoto / préf. de Barbara J. LONDON, Museum of Modern Art, New York (Etats-Unis), 19.04.-19.06.1979.

Videoscape : an Exhibition of Video Art / Marty DUNN, Peggy GALE, Gary Neill KENNEDY, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Ont. (Canada), 20.11.1974-01.04.1975.

Video-sonorité : la vidéo naît du bruit / sous la dir. de Jean GAGNON, Musée des beaux-arts du Canada, Ottawa, Ont. (Canada), 06.10.1994-02.01.1995.

Video Spaces, Eight Installations / Barbara LONDON, Museum of Modern Art, New York (Etats-Unis), 22.06.-12.09.1995.

Video Spain, ExiT Art, New York (Etats-Unis), 1988.

Vidéo sculptures / Dominique BELLOIR, Bernard MARCADÉ, Charles DREYFUS, Michel GIROUD, ARCA, Centre d’art contemporain, Marseille (France), 03-22.06.1985.

Video : The Distinctive Features of the Medium, Video Art, Institute of Contemporary Art University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pa. (Etats-Unis), 17.01.-28.02.1975.

Video Times, Serpertine Gallery, Londres (Royaume-Uni), 01-26.05.1975.

Video Tapes, Kölnische Kunstverein, Cologne (Allemagne), 06.07.-08.08.1974.

VIP : Albert Benamou présente VIP, vidéo-image(s)-peinture / Stephen SARRAZIN, Galerie du Génie, Paris (France), 20.10.-20.11.1990.

Voices = Voces = Voix / sous la dir. de Christopher PHILLIPS [catalogue de l’exposition itinérante], Rotterdam, Barcelone, Tourcoing, 1998-1999. Rotterdam (Pays-Bas),

Witte de With, 1998 ; Barcelone (Espagne), Fundació Joan Miró, 1998 ; Tourcoing (France), Le Fresnoy, 1999.

What a Wonderful World : Musicvideos in Architecture / Frans HAKS et Niek VERDONK, Groninger Museum, Groningen (Pays-Bas), 1990.

White Cube, Black Box : Skulpturensammlung, Video, Installation, Film / sous la dir. de Sabine BREITWIESER, Generali Foundation, Vienne (Autriche), 26.01.-14.04.1996.

X-Y : / Stéphanie MOISDON, Nicolas TREMBLEY, Christine VAN ASSCHE, Musée national d’art moderne-Centre de création industrielle, Paris (France), 26.10.1995-12.02.1996.

Catalogues de festivals

Argos festival, Bruxelles (Belgique), depuis 1989.

Artec, International Biennale in Nagoya, Nagoya (Japon), depuis 1989.

Artifices, Saint-Denis (France), depuis 1990.

Artlab, Tokyo (Japon), depuis 1991.

Ars Electronica, Linz (Autriche), depuis 1986.

Australian Video Festival, Sydney (Australie), depuis 1986.

AVE, International audiovisual experimental festival, Arnhem (Pays Bas), depuis 1986.

Bandits-mages, Bourges (France), depuis 1992.

Bienal de la imagen en movimiento, (Espagne) [dans différents lieux], depuis 1985.

Bienal de São Paolo, São Paolo (Brésil), depuis 1951.

La Biennale de Paris, Paris (France), 1972-1985.

Biennale de l’image, Paris (France), depuis 1998.

Biennale de l’image en mouvement, Centre pour l’image contemporaine Saint-Gervais, Genève (Suisse), depuis 1985.

Biennale de Lyon d’art contemporain, Lyon (France), depuis 1991, section vidéo depuis 1995.

Biennale de Montréal, Montréal, Québec (Canada), depuis 1998.

La Biennale di Venezia, Venise (Italie), depuis 1982.

Biennale internationale de l’image, Nancy (France), auparavant Festival international de l’image, depuis 1979.

Biennial of Sydney, Sydney (Australie), depuis 1979.

Documenta, Internationale Ausstellungen moderner Kunst, Cassel (Allemagne), depuis 1972.

Experimenta, Melbourne (Australie), depuis 1988.

Festival des arts électroniques, Rennes (France), 1986-2001.

Festival européen d’art des médias, Osnabrück (Allemagne), depuis 1988.

Festival International de l’Image, photographie, cinéma et multimedia, Vevey (Suisse), 1995-2000.

Festival international du nouveau cinéma et de la vidéo, Montréal, Québec (Canada), section vidéo depuis 1982.

Festival nacional de video, Círculo de bellas artes, Madrid (Espagne), 1984 et 1986.

Film-, Video-und Multimedia-Festival Luzern (VIPER), Lucerne (Suisse), depuis 1970.

GAMVideoFestival, Galleria civica d’arte moderna e contemporanea, Turin (Italie), depuis 2002.

Japan Video Television Festival at Spiral, Tokyo (Japon), depuis 1988.

Imagina, Monaco (France) ; CNIT La Défense (France), depuis 1999.

International Film Festival, Rotterdam (Pays-Bas), depuis 1971.

ICA Biennial of Independant Film and Video, Londres (Royaume-Uni), depuis 1992.

International Open Encounter on Video, CAYC, Centro de arte y comunicación, Buenos Aires (Argentine) [dans différents lieux], depuis 1972.

International Sound Basis Visual Art Festival, Wroclaw (Pologne), depuis 1991.

London Festival of Moving Images, Londres (Royaume-Uni), depuis 1996.

Manifestation internationale de vidéo et télévision, Montbéliard (France), 1982-1992.

Marler Video-Kunst Preis, Marl (Allemagne), depuis 1986.

Das Medienkunstfestival des ZKM, Karlsruhe (Allemagne), depuis 1992.

Merseyside’s International Video Festival, Liverpool (Royaume-Uni), depuis 1991.

National Video Festival, American Film Institute, Los Angeles (Etats-Unis), depuis 1982.

Paris photo, Salon international de la photographie, Paris (France), section vidéo depuis 2001.

Perú-video-arte-electronico : memorias del festival internacional de video-arte-electrónica, Lima (Pérou), 2003, depuis 1997.

Salso Film TV Festival, Salsomaggiore (Italie), depuis 1978.

Semaine internationale de Vidéo, MJC Saint-Gervais, Genève (Suisse), depuis 1985.

SONAR, Barcelone (Espagne), depuis 1994.

Vidéo Art Plastiques, Hérouville Saint-Clair (France), depuis 1987.

Video positive, Liverpool (Royaume-Uni), FACT, Foundation for Art & Creative Technology, depuis 1995.

Vidéoformes, festival de la création vidéo, Clermont-Ferrand (France), depuis 1986.

Videonale Bonn, Bonn (Allemagne), depuis 1985.

Visibilità zero, rassegna internazionale del video d’autore, (Italie, différents lieux), depuis 1997.

Whitney Museum of American Art Biennal, New York (Etats-Unis), depuis 1932.

World Wide Video festival, Kijkhuis, La Haye (Pays-Bas), depuis 1982.

World Wide Video festival, Amsterdam (Pays-Bas), depuis 1984.

Articles et essais

APPADURAI Arjun, ” Grassroots Globalization and the Research Imagination “, Public Culture, n° spécial ” Globalisation ” vol. 12, n° 1, Chicago, Ill. (Etats-Unis), 2000.

APPADURAI Arjun, ” Disjuncture and Difference in the Global Cultural Economy “, Public Culture, vol. 2, n° 2, Chicago, Ill. (Etats-Unis), 1990.

APPADURAI Arjun, ” Disjuncture and Difference in the Global Cultural Economy, Modernity at Large ” / sélection par Hou Hanru, Cream, Contemporary Art in Culture : 10 Curators, 10 Writers, 100 Artists, Londres (Royaume-Uni), Phaidon, 1998, p. 21-24.

BARTHES Roland, ” La Mort de l’auteur “, Le Bruissement de la langue. Paris (France), Editions du Seuil, 1984, p. 61-69.

BELLOUR Raymond, ” La forme où passe mon regard “, Dans la vision périphérique du témoin, Marcel Odenbach, Paris (France), Editions du Centre Pompidou, 1987, p. 10-19.

BITOMSKY Hartmund, ” Cinéma, vidéo et histoire “, Face à l’histoire 1933-1996, l’artiste moderne devant l’événement historique, Paris (France), Editions du Centre Pompidou, 1996, p. 552-556.

BLISTÈNE Bernard, ” ‘Espérez-vous vivre quelque chose d’extraordinaire dans ce lieu ?’ demande le vieil homme au plus jeune “, Dans la vision périphérique du témoin : Marcel Odenbach, Paris (France), Editions du Centre Pompidou, 1987, p. 22-23.

CAMOLLI Jean-Louis, RANCIÈRE Jacques, ” L’inoubliable “, Arrêt sur histoire, Paris (France), Editions du Centre Pompidou, 1997 (Supplémentaires, n. 4).

CHEVALIER Denis, ” Ouverture du champ musical “, Monter-sampler : l’échantillonnage généralisé, Paris (France), Editions du Centre Pompidou, 2000 (Scratch Projection), p. 70-72. P. (74, 76, 78, 80).

DUBOIS Philippe, ” La passion, la douleur et la grâce, note sur le cinéma et la vidéo dans la dernière décennie (1977-1987) “, L’époque, la mode, la morale, la passion : aspects de l’art d’aujourd’hui 1977-1987, Paris (France), Editions du Centre Pompidou, 1987, p. 74-87.

DURAND Régis, ” Toute l’histoire du monde dans une image … à propos d’Harun Farocki “, Art press, Paris (France), n. 190, avril 1994.

FARGIER Jean-Paul, ” Où va la vidéo ? “, Cahiers du cinéma, hors série, Paris (France), 1986.

FLECK Robert, ” L’actualité du happening “, Hors limites, l’art et la vie, 1952-1994, Paris (France), Editions du Centre Pompidou, 1994, p. 310-317.

HEINTZ Julie, ” La question des médias “, Joseph Beuys, Paris (France), Editions du Centre Pompidou, 1994, p. 284-288.

KAPROW Allan, ” L’art vidéo : vieux vin, nouvelle bouteille “, L’art et la vie confondus, Paris (France), Editions du Centre Pompidou, 1996, p. 182-187.

LAGEIRA Jacinto, ” L’image du monde dans le corps du texte “, Gary Hill, Paris (France), Editions du Centre Pompidou, 1992, p. 34-70.

MANOVICH Lev, ” Echantillonner, mixer l’esthétique de la sélection dans les anciens et les nouveaux médias “, Monter-sampler : l’échantillonnage généralisé, Paris (France), Editions du Centre Pompidou ; (Scratch Projection), 2000, P. 46-48, 50, 52, 54, 56, 58, 60.

MASSÉRA Jean-Charles, ” Danse avec la loi “, Bruce Nauman : image-texte 1966-1996, Paris (France), Editions du Centre Pompidou, 1997, p. 20-33.

PAIK Nam June [entretien], ” Nam June Paik, Fluxus a changé le monde “, Hors limites, l’art et la vie, 1952-1994, Paris (France), Editions du Centre Pompidou, 1994, p. 177-187

PAIK Nam June, ” L’homme qui est mort deux fois “, Joseph Beuys, Paris (France), Editions du Centre Pompidou, 1994, p. 362-363

POSCHARDT Ulf, ” Le Sampling à l’époque de son utilisabilité technique “, Nomad’s Land, n° 3, printemps-été 1998, p. 18-22, [extrait de Ulf Poschardt, Dj Culture, Hambourg, Rogner und Bernhard bei Zweitausendeins, 1995].

ROSOLATO Guy, ” La voix : entre corps et language “, Revue française de psychanalyse, Editions PUF, Paris (France), vol. 38, n. 1, janvier 1974.

ROYOUX Jean-Christophe, ” Le conflit des communications = Kommunikationskonflikte = The conflict of communications “, Stan Douglas, Paris (France), Editions du Centre Pompidou, 1994, p. 24-71.

ROYOUX Jean-Christophe, ” Pour un cinéma d’exposition, retour sur quelques jalons historiques “, Omnibus, Paris (France), n. 20, avril, 1997.

ROYOUX Jean-Christophe, ” Expanded-Extended. Héritage, transformation et ramification d’un concept esthétique dans l’art des années 60 “, 1 : Omnibus, Paris (France), n. 23, janvier 1998, 2 : Omnibus, Paris (France), n. 24, avril 1998.

VAN ASSHE Christine, ” La vidéo, 14 ans plus tard “, L’époque, la mode, la morale, la passion : aspects de l’art d’aujourd’hui, 1977-1987, Paris (France), Editions du Centre Pompidou, 1987, p. 332-356.

VAN ASSHE Christine, ” People die of exposure “, Bruce Nauman : image-texte 1966-1996, Paris (France), Editions du Centre Pompidou, 1997.

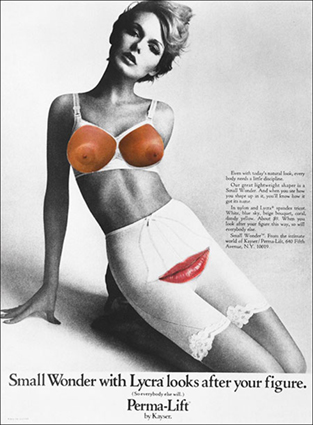

Martha Rosler, Untitled (Small Wonder), 1972. Photomontage.

Martha Rosler, Untitled (Small Wonder), 1972. Photomontage.