|

«επιτελεστικές εν-καταστάσεις»

(«performative in-stallations») Επιτελέσεις που καταλήγουν σε έργα τέχνης –εγκαταστάσεις. Εγκαίνια 9 Μαΐου 2013 στις 19.00

Ημερομηνίες για τις επιτελέσεις: 9,10,11|05|2013 στις 19.00 & 20.00 14|05|2013 στις 19.00 Artist talks: Σάββατο 25 Μαΐου, στις 14.00 To Κέντρο Τέχνης & Πολιτισμού Beton7, παρουσιάζει από 9 – 30 Μαΐου 2013 επιτελέσεις που καταλήγουν σε έργα τέχνης – εγκαταστάσεις του Δημοσθένη Αγραφιώτη. Οι επιτελέσεις (performances) έχουν χαρακτήρα συμμετοχικό, δηλαδή, απαιτούν την ενεργό συμβολή των ‘θεατών’. Το τελικό αποτέλεσμα συγκροτεί την έκθεση των παραχθέντων υλικών συνθεμάτων.

Στην όλη διαδικασία συνδράμουν οι: Αντρέας Πασιάς, Θοδωρής Παπαθεοδώρου και Απόστολος Πλαχούρης. Η επιτέλεση (performance) ως ανταλλαγή ενέργειας ανάμεσα στο σώμα του καλλιτέχνη και τα σώματα των συμμετεχόντων μπορεί να καταλήξει στη διαμόρφωση τέχνεργων, αντικειμένων, εικόνων, ήχων. Σύμφωνα μ αυτή την εκδοχή της επιτέλεσης, το παραγόμενο σύνολο θα μπορούσε να διεκδικήσει την υπόσταση του ‘έργου τέχνης’, ‘αισθητικού αντικειμένου’, ή ‘εγκατάστασης’ (installation); Με μιαν άλλη έκφραση, η επιτέλεση θα μπορούσε να έχει διπλό ρόλο: (i) να αποτελέσει αυτόνομη καλλιτεχνική διαδικασία, (ii) να λειτουργήσει ως μηχανισμός παραγωγής καλλιτεχνημάτων; ΕΠΤΑ ΕΠΙΤΕΛΕΣΕΙΣ Ο Δημοσθένης Αγραφιώτης είναι ποιητής, εικαστικός καλλιτέχνης διαμέσων (ζωγραφική, φωτογραφική, διαμέσα/intermedia, performance/επιτέλεση, εγκαταστάσεις). Συγγραφέας βιβλίων με δοκίμια και επιστημονικά άρθρα για την τέχνη, την επιστήμη/τεχνολογία, υγεία ως κοινωνικο-πολιτιστικά φαινόμενα και τη νεοτερικότητα. Ατομικές και συλλογικές εκθέσεις ζωγραφικής, φωτογραφικής και οπτικής/εικονοσχηματικής ποίησης στην Ελλάδα και στο εξωτερικό. Συμμετοχές σε εκδόσεις, κοινωνικο-πολιτιστικές εκδηλώσεις, ταχυδρομική τέχνη, πολυμέσα και διαμέσα, εγκαταστάσεις (ιnstallations) επιτελέσεις (performances), “εναλλακτικές” καλλιτεχνικές δραστηριότητες. Ειδικό ενδιαφέρον για τις συζεύξεις τέχνης και νέων τεχνολογιών – τεχνοεπιστήμης. Έκδοση φυλλαδίου τέχνης ‘Κλίναμεν’ (1980-90) περιοδικού «Κλίναμεν» (Εκδ. Ερατώ, 1990-94) και παραγωγή βιβλίων – καλλιτεχνημάτων (artists books) ‘Κλίναμεν’. ‘Κλίναμεν’ ηλεκτρονικό (2001-). LINKS |

tags-elements

starting-ending

opening-closing concept

head section

body section

………..listen to the tutorial

texts-images-sounds

uowm ftp server //

1.8 HTML vs XHTML

non-normative.

text/html MIME type, then it will be processed as an HTML document by Web browsers. This specification defines the latest HTML syntax, known simply as “HTML”.application/xhtml+xml, then it is treated as an XML document by Web browsers, to be parsed by an XML processor. Authors are reminded that the processing for XML and HTML differs; in particular, even minor syntax errors will prevent a document labeled as XML from being rendered fully, whereas they would be ignored in the HTML syntax. This specification defines the latest XHTML syntax, known simply as “XHTML”.noscript feature can be represented using the HTML syntax, but cannot be represented with the DOM or in the XHTML syntax. Comments that contain the string “-->” can only be represented in the DOM, not in the HTML and XHTML syntaxes.αρχικό παράδειγμα γραφής dom html

A document with a short head

...

An application with a long head

http://support.js

...

ex

|

|

The theory of mass culture-or mass audience culture, commercial culture, “popular”

culture, the culture industry, as it is variously known-has always tended to define its object

against so-called high culture without reflecting on the objective status of this opposition.

As so often, positions in this field reduce themselves to two mirror-images, and are

essentially staged in terms of value. Thus the familiar motif of elitism argues for the priority

of mass culture on the grounds of the sheer numbers of people exposed to it; the pursuit of

high or hermetic culture is then stigmatized as a status hobby of small groups of

intellectuals. As its anti-intellectual thrust suggests, this essentially negative position has

little theoretical content but clearly responds to a deeply rooted conviction in American

radicalism and articulates a widely based sense that high culture is an establishment

phenomenon, irredeemably tainted by its association with institutions, in particular with

the university. The value invoked is therefore a social one: it would be preferable to deal

with tv programs, The Godfather, orJaws, rather than with Wallace Stevens or HenryJames,

because the former clearly speak a cultural language meaningful to far wider strata of the

population than what is socially represented by intellectuals. Radicals are however also

intellectuals, so that this position has suspicious overtones of the guilt trip; meanwhile it

overlooks the anti-social and critical, negative (although generally not revolutionary)

stance of much of the most important forms of modem art; finally, it offers no method for

reading even those cultural objects it valorizes and has had little of interest to say about

their content

**html

Presentation related attributes

background(Deprecated. use CSS instead.) andbgcolor(Deprecated. use CSS instead.) attributes forbody(required element according to the W3C.) element.align(Deprecated. use CSS instead.) attribute ondiv,form, paragraph (p) and heading (h1…h6) elementsalign(Deprecated. use CSS instead.),noshade(Deprecated. use CSS instead.),size(Deprecated. use CSS instead.) andwidth(Deprecated. use CSS instead.) attributes onhrelementalign(Deprecated. use CSS instead.),border,vspaceandhspaceattributes onimgandobject(caution: theobjectelement is only supported in Internet Explorer (from the major browsers)) elementsalign(Deprecated. use CSS instead.) attribute onlegendandcaptionelementsalign(Deprecated. use CSS instead.) andbgcolor(Deprecated. use CSS instead.) ontableelementnowrap(Obsolete),bgcolor(Deprecated. use CSS instead.),width,heightontdandthelementsbgcolor(Deprecated. use CSS instead.) attribute ontrelementclear(Obsolete) attribute onbrelementcompactattribute ondl,dirandmenuelementstype(Deprecated. use CSS instead.),compact(Deprecated. use CSS instead.) andstart(Deprecated. use CSS instead.) attributes onolandulelementstypeandvalueattributes onlielementwidthattribute onpreelement

HTML is written in the form of HTML elements consisting of tags enclosed in angle brackets (like ), within the web page content. HTML tags most commonly come in pairs like

and

, although some tags, known as empty elements, are unpaired, for example

Sample page

Sample page

This is a simple sample.

- The exact list of which features a user agents supports.

- The maximum allowed stack depth for recursion in script.

- Features that describe the user’s environment, like Media Queries and the

Screenobject. [MQ] [CSSOMVIEW] - The user’s time zone.

1.11 A quick introduction to HTML

Sample page

Sample page

This is a simple sample.

This is very wrong!

This is correct.

a element and itshref attribute:simple

=” character. The attribute value can remainunquoted if it doesn’t contain space characters or any of " ' ` = < or >. Otherwise, it has to be quoted using either single or double quotes. The value, along with the “=” character, can be omitted altogether if the value is the empty string.DocumentType node, Element nodes, Text nodes, Comment nodes, and in some cases ProcessingInstruction nodes.- DOCTYPE:

html html

html element, which is the element always found at the root of HTML documents. It contains two elements,head and body, as well as a Text node between them.Text nodes in the DOM tree than one would initially expect, because the source contains a number of spaces (represented here by “␣”) and line breaks (“⏎”) that all end up as Text nodes in the DOM. However, for historical reasons not all of the spaces and line breaks in the original markup appear in the DOM. In particular, all the whitespace before head start tag ends up being dropped silently, and all the whitespace after the body end tag ends up placed at the end of the body.head element contains a title element, which itself contains a Text node with the text “Sample page”. Similarly, the body element contains an h1 element, a p element, and a comment.script element or using event handler content attributes. For example, here is a form with a script that sets the value of the form’s outputelement to say “Hello World”:<form name="main">

Result: <output name="result">

<script>

document.forms.main.elements.result.value = 'Hello World';

a element in the tree above) can have its “href” attribute changed in several ways:var a = document.links[0]; // obtain the first link in the document

a.href = 'sample.html'; // change the destination URL of the link

a.protocol = 'https'; // change just the scheme part of the URL

a.setAttribute('href', 'http://example.com/'); // change the content attribute directly

Sample styled page

body { background: navy; color: yellow; }

Sample styled page

This page is just a demo.

1.11.1 Writing secure applications with HTML

- Not validating user input

- Cross-site scripting (XSS)

- SQL injection

-

When accepting untrusted input, e.g. user-generated content such as text comments, values in URL parameters, messages from third-party sites, etc, it is imperative that the data be validated before use, and properly escaped when displayed. Failing to do this can allow a hostile user to perform a variety of attacks, ranging from the potentially benign, such as providing bogus user information like a negative age, to the serious, such as running scripts every time a user looks at a page that includes the information, potentially propagating the attack in the process, to the catastrophic, such as deleting all data in the server.When writing filters to validate user input, it is imperative that filters always be whitelist-based, allowing known-safe constructs and disallowing all other input. Blacklist-based filters that disallow known-bad inputs and allow everything else are not secure, as not everything that is bad is yet known (for example, because it might be invented in the future).For example, suppose a page looked at its URL’s query string to determine what to display, and the site then redirected the user to that page to display a message, as in:If the message was just displayed to the user without escaping, a hostile attacker could then craft a URL that contained a script element:

http://example.com/message.cgi?say=%3Cscript%3Ealert%28%27Oh%20no%21%27%29%3C/script%3E

If the attacker then convinced a victim user to visit this page, a script of the attacker’s choosing would run on the page. Such a script could do any number of hostile actions, limited only by what the site offers: if the site is an e-commerce shop, for instance, such a script could cause the user to unknowingly make arbitrarily many unwanted purchases.This is called a cross-site scripting attack.There are many constructs that can be used to try to trick a site into executing code. Here are some that authors are encouraged to consider when writing whitelist filters:- When allowing harmless-seeming elements like

img, it is important to whitelist any provided attributes as well. If one allowed all attributes then an attacker could, for instance, use theonloadattribute to run arbitrary script. - When allowing URLs to be provided (e.g. for links), the scheme of each URL also needs to be explicitly whitelisted, as there are many schemes that can be abused. The most prominent example is “

javascript:“, but user agents can implement (and indeed, have historically implemented) others. - Allowing a

baseelement to be inserted means anyscriptelements in the page with relative links can be hijacked, and similarly that any form submissions can get redirected to a hostile site.

- When allowing harmless-seeming elements like

- Cross-site request forgery (CSRF)

-

If a site allows a user to make form submissions with user-specific side-effects, for example posting messages on a forum under the user’s name, making purchases, or applying for a passport, it is important to verify that the request was made by the user intentionally, rather than by another site tricking the user into making the request unknowingly.This problem exists because HTML forms can be submitted to other origins.Sites can prevent such attacks by populating forms with user-specific hidden tokens, or by checking

Originheaders on all requests. - Clickjacking

-

A page that provides users with an interface to perform actions that the user might not wish to perform needs to be designed so as to avoid the possibility that users can be tricked into activating the interface.One way that a user could be so tricked is if a hostile site places the victim site in a small

iframeand then convinces the user to click, for instance by having the user play a reaction game. Once the user is playing the game, the hostile site can quickly position the iframe under the mouse cursor just as the user is about to click, thus tricking the user into clicking the victim site’s interface.

1.11.2 Common pitfalls to avoid when using the scripting APIs

img elements and the load event. The event could fire as soon as the element has been parsed, especially if the image has already been cached (which is common).

var img = new Image();

img.src = 'games.png';

img.alt = 'Games';

img.onload = gamesLogoHasLoaded;

// img.addEventListener('load', gamesLogoHasLoaded, false); // would work also

img element and then in a separate script added the event listeners, there’s a chance that theload event would be fired in between, leading it to be missed:

<!-- the 'load' event might fire here while the parser is taking a

break, in which case you will not see it! -->

var img = document.getElementById('games');

img.onload = gamesLogoHasLoaded; // might never fire!

1.12 Conformance requirements for authors

1.12.1 Presentational markup

- The use of presentational elements leads to poorer accessibility

-

While it is possible to use presentational markup in a way that provides users of assistive technologies (ATs) with an acceptable experience (e.g. using ARIA), doing so is significantly more difficult than doing so when using semantically-appropriate markup. Furthermore, even using such techniques doesn’t help make pages accessible for non-AT non-graphical users, such as users of text-mode browsers.Using media-independent markup, on the other hand, provides an easy way for documents to be authored in such a way that they work for more users (e.g. text browsers).

- Higher cost of maintenance

-

It is significantly easier to maintain a site written in such a way that the markup is style-independent. For example, changing the color of a site that uses

throughout requires changes across the entire site, whereas a similar change to a site based on CSS can be done by changing a single file. - Larger document sizes

-

Presentational markup tends to be much more redundant, and thus results in larger document sizes.

style attribute and the style element. Use of the style attribute is somewhat discouraged in production environments, but it can be useful for rapid prototyping (where its rules can be directly moved into a separate style sheet later) and for providing specific styles in unusual cases where a separate style sheet would be inconvenient. Similarly, thestyle element can be useful in syndication or for page-specific styles, but in general an external style sheet is likely to be more convenient when the styles apply to multiple pages.b, i, hr, s, small, and u.1.12.2 Syntax errors

- Unintuitive error-handling behavior

-

Certain invalid syntax constructs, when parsed, result in DOM trees that are highly unintuitive.For example, the following markup fragment results in a DOM with an

hrelement that is an earlier sibling of the correspondingtableelement:

...- Errors with optional error recovery

To allow user agents to be used in controlled environments without having to implement the more bizarre and convoluted error handling rules, user agents are permitted to fail whenever encountering a parse error.- Errors where the error-handling behavior is not compatible with streaming user agents

Some error-handling behavior, such as the behavior for the

... example mentioned above, are incompatible with streaming user agents (user agents that process HTML files in one pass, without storing state). To avoid interoperability problems with such user agents, any syntax resulting in such behavior is considered invalid.

- Errors that can result in infoset coercion

When a user agent based on XML is connected to an HTML parser, it is possible that certain invariants that XML enforces, such as comments never containing two consecutive hyphens, will be violated by an HTML file. Handling this can require that the parser coerce the HTML DOM into an XML-compatible infoset. Most syntax constructs that require such handling are considered invalid.- Errors that result in disproportionally poor performance

Certain syntax constructs can result in disproportionally poor performance. To discourage the use of such constructs, they are typically made non-conforming.For example, the following markup results in poor performance, since all the unclosedielements have to be reconstructed in each paragraph, resulting in progressively more elements in each paragraph:He dreamt.

He dreamt that he ate breakfast.

Then lunch.

And finally dinner.

The resulting DOM for this fragment would be:- Errors involving fragile syntax constructs

There are syntax constructs that, for historical reasons, are relatively fragile. To help reduce the number of users who accidentally run into such problems, they are made non-conforming.For example, the parsing of certain named character references in attributes happens even with the closing semicolon being omitted. It is safe to include an ampersand followed by letters that do not form a named character reference, but if the letters are changed to a string that does form a named character reference, they will be interpreted as that character instead.In this fragment, the attribute’s value is “?bill&ted“:Bill and Ted

In the following fragment, however, the attribute’s value is actually “?art©“, not the intended “?art©“, because even without the final semicolon, “©” is handled the same as “©” and thus gets interpreted as “©“:Art and Copy

To avoid this problem, all named character references are required to end with a semicolon, and uses of named character references without a semicolon are flagged as errors.Thus, the correct way to express the above cases is as follows:Bill and Ted

Art and Copy <!-- the & has to be escaped, since © is a named character reference -->

- Errors involving known interoperability problems in legacy user agents

Certain syntax constructs are known to cause especially subtle or serious problems in legacy user agents, and are therefore marked as non-conforming to help authors avoid them.For example, this is why the U+0060 GRAVE ACCENT character (`) is not allowed in unquoted attributes. In certain legacy user agents, it is sometimes treated as a quote character.Another example of this is the DOCTYPE, which is required to trigger no-quirks mode, because the behavior of legacy user agents in quirks mode is often largely undocumented.- Errors that risk exposing authors to security attacks

Certain restrictions exist purely to avoid known security problems.For example, the restriction on using UTF-7 exists purely to avoid authors falling prey to a known cross-site-scripting attack using UTF-7.- Cases where the author’s intent is unclear

Markup where the author’s intent is very unclear is often made non-conforming. Correcting these errors early makes later maintenance easier.- Cases that are likely to be typos

When a user makes a simple typo, it is helpful if the error can be caught early, as this can save the author a lot of debugging time. This specification therefore usually considers it an error to use element names, attribute names, and so forth, that do not match the names defined in this specification.For example, if the author typedinstead of- Errors that could interfere with new syntax in the future

In order to allow the language syntax to be extended in the future, certain otherwise harmless features are disallowed.For example, “attributes” in end tags are ignored currently, but they are invalid, in case a future change to the language makes use of that syntax feature without conflicting with already-deployed (and valid!) content.Some authors find it helpful to be in the practice of always quoting all attributes and always including all optional tags, preferring the consistency derived from such custom over the minor benefits of terseness afforded by making use of the flexibility of the HTML syntax. To aid such authors, conformance checkers can provide modes of operation wherein such conventions are enforced.1.12.3 Restrictions on content models and on attribute values

This section is non-normative.Beyond the syntax of the language, this specification also places restrictions on how elements and attributes can be specified. These restrictions are present for similar reasons:- Errors involving content with dubious semantics

-

To avoid misuse of elements with defined meanings, content models are defined that restrict how elements can be nested when such nestings would be of dubious value.

- Errors that involve a conflict in expressed semantics

-

Similarly, to draw the author’s attention to mistakes in the use of elements, clear contradictions in the semantics expressed are also considered conformance errors.In the fragments below, for example, the semantics are nonsensical: a separator cannot simultaneously be a cell, nor can a radio button be a progress bar.

- Cases where the default styles are likely to lead to confusion

-

Certain elements have default styles or behaviors that make certain combinations likely to lead to confusion. Where these have equivalent alternatives without this problem, the confusing combinations are disallowed.For example,

divelements are rendered as block boxes, andspanelements as inline boxes. Putting a block box in an inline box is unnecessarily confusing; since either nesting justdivelements, or nesting justspanelements, or nestingspanelements insidedivelements all serve the same purpose as nesting adivelement in aspanelement, but only the latter involves a block box in an inline box, the latter combination is disallowed.Another example would be the way interactive content cannot be nested. For example, abuttonelement cannot contain atextareaelement. This is because the default behavior of such nesting interactive elements would be highly confusing to users. Instead of nesting these elements, they can be placed side by side. - Errors that indicate a likely misunderstanding of the specification

-

Sometimes, something is disallowed because allowing it would likely cause author confusion.For example, setting the

disabledattribute to the value “false” is disallowed, because despite the appearance of meaning that the element is enabled, it in fact means that the element is disabled (what matters for implementations is the presence of the attribute, not its value). - Errors involving limits that have been imposed merely to simplify the language

-

Some conformance errors simplify the language that authors need to learn.For example, the

areaelement’sshapeattribute, despite accepting bothcircandcirclevalues in practice as synonyms, disallows the use of thecircvalue, so as to simplify tutorials and other learning aids. There would be no benefit to allowing both, but it would cause extra confusion when teaching the language. - Errors that involve peculiarities of the parser

-

Certain elements are parsed in somewhat eccentric ways (typically for historical reasons), and their content model restrictions are intended to avoid exposing the author to these issues.For example, a

formelement isn’t allowed inside phrasing content, because when parsed as HTML, aformelement’s start tag will imply apelement’s end tag. Thus, the following markup results in two paragraphs, not one:Welcome. Name:

It is parsed exactly like the following:Welcome.

Name: - Errors that would likely result in scripts failing in hard-to-debug ways

-

Some errors are intended to help prevent script problems that would be hard to debug.This is why, for instance, it is non-conforming to have two

idattributes with the same value. Duplicate IDs lead to the wrong element being selected, with sometimes disastrous effects whose cause is hard to determine. - Errors that waste authoring time

-

Some constructs are disallowed because historically they have been the cause of a lot of wasted authoring time, and by encouraging authors to avoid making them, authors can save time in future efforts.For example, a

scriptelement’ssrcattribute causes the element’s contents to be ignored. However, this isn’t obvious, especially if the element’s contents appear to be executable script — which can lead to authors spending a lot of time trying to debug the inline script without realizing that it is not executing. To reduce this problem, this specification makes it non-conforming to have executable script in ascriptelement when thesrcattribute is present. This means that authors who are validating their documents are less likely to waste time with this kind of mistake. - Errors that involve areas that affect authors migrating to and from XHTML

-

Some authors like to write files that can be interpreted as both XML and HTML with similar results. Though this practice is discouraged in general due to the myriad of subtle complications involved (especially when involving scripting, styling, or any kind of automated serialization), this specification has a few restrictions intended to at least somewhat mitigate the difficulties. This makes it easier for authors to use this as a transitionary step when migrating between HTML and XHTML.For example, there are somewhat complicated rules surrounding the

langandxml:langattributes intended to keep the two synchronized.Another example would be the restrictions on the values ofxmlnsattributes in the HTML serialization, which are intended to ensure that elements in conforming documents end up in the same namespaces whether processed as HTML or XML. - Errors that involve areas reserved for future expansion

-

As with the restrictions on the syntax intended to allow for new syntax in future revisions of the language, some restrictions on the content models of elements and values of attributes are intended to allow for future expansion of the HTML vocabulary.For example, limiting the values of the

targetattribute that start with an U+005F LOW LINE character (_) to only specific predefined values allows new predefined values to be introduced at a future time without conflicting with author-defined values. - Errors that indicate a mis-use of other specifications

-

Certain restrictions are intended to support the restrictions made by other specifications.For example, requiring that attributes that take media queries use only valid media queries reinforces the importance of following the conformance rules of that specification.

1.13 Suggested reading

This section is non-normative.The following documents might be of interest to readers of this specification.- Character Model for the World Wide Web 1.0: Fundamentals [CHARMOD]

-

This Architectural Specification provides authors of specifications, software developers, and content developers with a common reference for interoperable text manipulation on the World Wide Web, building on the Universal Character Set, defined jointly by the Unicode Standard and ISO/IEC 10646. Topics addressed include use of the terms ‘character’, ‘encoding’ and ‘string’, a reference processing model, choice and identification of character encodings, character escaping, and string indexing.

- Unicode Security Considerations [UTR36]

-

Because Unicode contains such a large number of characters and incorporates the varied writing systems of the world, incorrect usage can expose programs or systems to possible security attacks. This is especially important as more and more products are internationalized. This document describes some of the security considerations that programmers, system analysts, standards developers, and users should take into account, and provides specific recommendations to reduce the risk of problems.

- Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.0 [WCAG]

-

Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.0 covers a wide range of recommendations for making Web content more accessible. Following these guidelines will make content accessible to a wider range of people with disabilities, including blindness and low vision, deafness and hearing loss, learning disabilities, cognitive limitations, limited movement, speech disabilities, photosensitivity and combinations of these. Following these guidelines will also often make your Web content more usable to users in general.

- Authoring Tool Accessibility Guidelines (ATAG) 2.0 [ATAG]

-

This specification provides guidelines for designing Web content authoring tools that are more accessible for people with disabilities. An authoring tool that conforms to these guidelines will promote accessibility by providing an accessible user interface to authors with disabilities as well as by enabling, supporting, and promoting the production of accessible Web content by all authors.

- User Agent Accessibility Guidelines (UAAG) 2.0 [UAAG]

-

This document provides guidelines for designing user agents that lower barriers to Web accessibility for people with disabilities. User agents include browsers and other types of software that retrieve and render Web content. A user agent that conforms to these guidelines will promote accessibility through its own user interface and through other internal facilities, including its ability to communicate with other technologies (especially assistive technologies). Furthermore, all users, not just users with disabilities, should find conforming user agents to be more usable.

4.2.3 The

baseelement- The

baseelement allows authors to specify the document base URL for the purposes of resolving relative URLs, and the name of the defaultbrowsing context for the purposes of following hyperlinks. The element does not represent any content beyond this information.Categories: - Metadata content.

- Contexts in which this element can be used:

- In a

headelement containing no otherbaseelements. - Content model:

- Empty.

- Tag omission in text/html:

- No end tag.

- Content attributes:

- Global attributes

href— Document base URLtarget— Default browsing context for hyperlink navigation and form submission- DOM interface:

-

interface HTMLBaseElement : HTMLElement {

attribute DOMString href;

attribute DOMString target;

};

There must be no more than onebaseelement per document.Thehrefcontent attribute, if specified, must contain a valid URL potentially surrounded by spaces.Abaseelement, if it has anhrefattribute, must come before any other elements in the tree that have attributes defined as taking URLs, except thehtmlelement (itsmanifestattribute isn’t affected bybaseelements).Thetargetattribute, if specified, must contain a valid browsing context name or keyword, which specifies which browsing context is to be used as the default when hyperlinks and forms in theDocumentcause navigation.Abaseelement, if it has atargetattribute, must come before any elements in the tree that represent hyperlinks.ThehrefIDL attribute, on getting, must return the result of running the following algorithm:-

If the

baseelement has nohrefcontent attribute, then return the document base URL and abort these steps. -

Let fallback base url be the

Document‘s fallback base URL. -

If the previous step was successful, return the resulting absolute URL and abort these steps.

-

Otherwise, return the empty string.

ThetargetIDL attribute must reflect the content attribute of the same name.In this example, abaseelement is used to set the document base URL:

This is an example for the <base> element

Visit the archives.

The link in the above example would be a link to “http://www.example.com/news/archives.html“.Δεν επιτρέπεται σχολιασμός στο b&h-pro-webd-tables-html-consuming-consumed-archive/ from simple html and js to dhtml , to html 5 and js sem 5-6arch-archiving-archives-papers-

ΑΝΑΒΑΛΕ ΓΙΑ ΛΙΓΟ ΤΟΝ ΘΑΝΑΤΟ ΣΟΥ, ΓΙΑ ΝΑ ΣΟΥ ΠΩ ΜΙΑ ΙΣΤΟΡΙΑ. ΙΣΤΟΡΙΕΣ, ΑΜΑΡΤΙΕΣ & ΜΕΓΑΛΑ ΛΑΘΗ («Οι σχολιαστές σημειώνουν σ’ αυτό το χωρίο: Η ορθή αντίληψη ενός ζητήματος και η παρανόηση ενός ζητήματος δεν αποκλείονται αμοιβαίως». Φραντς Κάφκα, “Η Δίκη”).Δούλευε κανονικά, με ωράριο, σε μεγάλη εταιρία, και ήταν επιφορτισμένος με το καθήκον να κάθεται στο γραφείο δίπλα στο μεγάλο παράθυρο, να κοιτάζει προς τα έξω και να σημειώνει πότε ο ουρανός πάνω από τα κεντρικά της εταιρίας ήταν εντελώς ηλιόλουστος, πότε μαζεύονταν σύννεφα, σε τι ποσοστό κάλυπταν τον ήλιο και για πόση ώρα, πότε ακριβώς ξεκίναγε και πότε ακριβώς τελείωνε η κάθε βροχή. Οι αρμοδιότητές του περιορίζονταν στη συμπλήρωση αυτών των ημερήσιων αναφορών, καθώς άλλα τμήματα ήταν επιφορτισμένα με την αρχειοθέτηση, επεξεργασία και στατιστική ανάλυσή τους. Η δουλειά του μπορεί να φαινόταν σχετικά απλή, ήταν ωστόσο σαφές πως δεν μπορούσε να την κάνει ο καθένας. Ο εταιρικός θρύλος έλεγε πως οι τρεις προκάτοχοί του στο συγκεκριμένο πόστο είχαν χάσει τα λογικά τους, καθώς η συννεφιά μπορεί απλά να σου χάλασει τη διάθεση και η λιακάδα απλά να στην φτιάξει όταν ασχολείσαι με άλλα πράγματα και ο ουρανός είναι μοναχά το φόντο. Όταν όμως η παρατήρηση του ουρανού γίνεται η κύρια απασχόλησή σου, αργά ή γρήγορα διαπιστώνεις πως υπάρχει κάτι που δεν αντέχεται στην έλευση της κάθε συννεφιάς. Εκείνος όμως ήταν φαίνεται φτιαγμένος από άλλα υλικά κι είχε έτσι διαψεύσει όλες τις προβλέψεις, έχοντας γίνει η αιτία να αλλάξουν πολλά λεφτά χέρια σε ενδοεταιρικά στοιχήματα, καθώς συμπλήρωνε ήδη ένα χρόνο, στον οποίο δεν είχε δείξει το παραμικρό σημάδι κλονισμού.Καθόταν, κοιτούσε και κατέγραφε. Καθόταν, κοιτούσε και κατέγραφε. Με ολοένα και μεγαλύτερη ακρίβεια, έχοντας αφήσει πίσω την απειρία των πρώτων μηνών. 9:32, σύννεφα πλησιάζουν από τον νότο / 9:38, συννεφιά καλύπτουσα το 10% της ατμόσφαιρας / 9:47, ουρανός εντελώς μουντός.Έμεινε στη θέση του δώδεκα χρόνια, πέντε μήνες και τέσσερεις ημέρες. Θα έμενε παραπάνω, αλλά η εταιρία άντεξε λιγότερο από αυτόν κι έκλεισε. Τον πρώτο καιρό της ανεργίας έψαξε με επιμονή για άλλη δουλειά, αλλά δεν κατάφερε να βρει τίποτα. Σιγά σιγά άρχισε να κλείνεται στο σπίτι του. Για να μη σκουριάζει, τοποθέτησε μια καρέκλα κι ένα τραπέζι δίπλα στο παράθυρο κι άρχισε να συμπληρώνει αναφορές κάθε μέρα.Καθόταν, κοιτούσε και κατέγραφε. Καθόταν, κοιτούσε και κατέγραφε. Όντας πλέον ο κύριος των αναφορών του, άρχισε να τις κολλάει στους τοίχους του σπίτιου του. Πρώτα κάλυψε το υπνοδωμάτιό του, μετά το σαλόνι, μετά ολόκληρο το σπίτι. Από τους τοίχους πέρασε στα πατώματα, μέχρι που τέλειωσαν κι αυτά. Μετά άρχισε να τις τοιχοκολλά στη γειτονιά του, ύστερα άρχισε να επεκτείνεται σε άλλες. Σίγουρα κάποιοι θα τις έβρισκαν χρήσιμες. Κι άλλωστε αυτό είχε μάθει να κάνει κι ήθελε να εξακολουθήσει να το κάνει καλά.Οι αναφορές στους τοίχους άρχισαν να κινούν την περιέργεια του κόσμου, μια μέρα τον εντόπισε ένας δημοσιογράφος, σύντομα την πρώτη συνέντευξη ακολούθησε η δεύτερη, κι απέκτησε έτσι ένα σχετικό στάτους.‘Ηταν γέρος πια, αλλά άξιζε τον κόπο, καθώς είδε να μαζεύονται σπίτι του νέα παιδιά που ήθελαν να μάθουν την τέχνη του. Κάθονταν δίπλα δίπλα κοντά στο παράθυρο κι αυτός από πάνω τους τους επέβλεπε ικανοποιημένος. Ναι, πολλοί από αυτούς τρελάθηκαν στην πορεία. Αλλά αυτή η δουλειά δεν ήταν για όλους.Λίγα χρόνια αργότερα είχε αποσυρθεί εντελώς και απλά καθόταν και χάζευε τον ουρανό. Καθόταν, κοιτούσε και δεν κατέγραφε. Καθόταν, κοιτούσε και δεν κατέγραφε. Μαζεύονταν σύννεφα κι αυτός τα κοιτούσε χαιρέκακα, ξέροντας πως η υποχρέωσή του απέναντί τους είχε τελειώσει. Τώρα μπορούσε να κλάψει. Αλλά δεν υπήρχε κανείς δίπλα του να καταγράψει τα δάκρυά του. Έτσι τα κράτησε μέσα του.Δεν επιτρέπεται σχολιασμός στο arch-archiving-archives-papers- Δούλευε κανονικά, με ωράριο, σε μεγάλη εταιρία, και ήταν επιφορτισμένος με το καθήκον να κάθεται στο γραφείο δίπλα στο μεγάλο παράθυρο, να κοιτάζει προς τα έξω και να σημειώνει πότε ο ουρανός πάνω από τα κεντρικά της εταιρίας ήταν εντελώς ηλιόλουστος, πότε μαζεύονταν σύννεφα, σε τι ποσοστό κάλυπταν τον ήλιο και για πόση ώρα, πότε ακριβώς ξεκίναγε και πότε ακριβώς τελείωνε η κάθε βροχή. Οι αρμοδιότητές του περιορίζονταν στη συμπλήρωση αυτών των ημερήσιων αναφορών, καθώς άλλα τμήματα ήταν επιφορτισμένα με την αρχειοθέτηση, επεξεργασία και στατιστική ανάλυσή τους. Η δουλειά του μπορεί να φαινόταν σχετικά απλή, ήταν ωστόσο σαφές πως δεν μπορούσε να την κάνει ο καθένας. Ο εταιρικός θρύλος έλεγε πως οι τρεις προκάτοχοί του στο συγκεκριμένο πόστο είχαν χάσει τα λογικά τους, καθώς η συννεφιά μπορεί απλά να σου χάλασει τη διάθεση και η λιακάδα απλά να στην φτιάξει όταν ασχολείσαι με άλλα πράγματα και ο ουρανός είναι μοναχά το φόντο. Όταν όμως η παρατήρηση του ουρανού γίνεται η κύρια απασχόλησή σου, αργά ή γρήγορα διαπιστώνεις πως υπάρχει κάτι που δεν αντέχεται στην έλευση της κάθε συννεφιάς. Εκείνος όμως ήταν φαίνεται φτιαγμένος από άλλα υλικά κι είχε έτσι διαψεύσει όλες τις προβλέψεις, έχοντας γίνει η αιτία να αλλάξουν πολλά λεφτά χέρια σε ενδοεταιρικά στοιχήματα, καθώς συμπλήρωνε ήδη ένα χρόνο, στον οποίο δεν είχε δείξει το παραμικρό σημάδι κλονισμού.Καθόταν, κοιτούσε και κατέγραφε. Καθόταν, κοιτούσε και κατέγραφε. Με ολοένα και μεγαλύτερη ακρίβεια, έχοντας αφήσει πίσω την απειρία των πρώτων μηνών. 9:32, σύννεφα πλησιάζουν από τον νότο / 9:38, συννεφιά καλύπτουσα το 10% της ατμόσφαιρας / 9:47, ουρανός εντελώς μουντός.Έμεινε στη θέση του δώδεκα χρόνια, πέντε μήνες και τέσσερεις ημέρες. Θα έμενε παραπάνω, αλλά η εταιρία άντεξε λιγότερο από αυτόν κι έκλεισε. Τον πρώτο καιρό της ανεργίας έψαξε με επιμονή για άλλη δουλειά, αλλά δεν κατάφερε να βρει τίποτα. Σιγά σιγά άρχισε να κλείνεται στο σπίτι του. Για να μη σκουριάζει, τοποθέτησε μια καρέκλα κι ένα τραπέζι δίπλα στο παράθυρο κι άρχισε να συμπληρώνει αναφορές κάθε μέρα.Καθόταν, κοιτούσε και κατέγραφε. Καθόταν, κοιτούσε και κατέγραφε. Όντας πλέον ο κύριος των αναφορών του, άρχισε να τις κολλάει στους τοίχους του σπίτιου του. Πρώτα κάλυψε το υπνοδωμάτιό του, μετά το σαλόνι, μετά ολόκληρο το σπίτι. Από τους τοίχους πέρασε στα πατώματα, μέχρι που τέλειωσαν κι αυτά. Μετά άρχισε να τις τοιχοκολλά στη γειτονιά του, ύστερα άρχισε να επεκτείνεται σε άλλες. Σίγουρα κάποιοι θα τις έβρισκαν χρήσιμες. Κι άλλωστε αυτό είχε μάθει να κάνει κι ήθελε να εξακολουθήσει να το κάνει καλά.Οι αναφορές στους τοίχους άρχισαν να κινούν την περιέργεια του κόσμου, μια μέρα τον εντόπισε ένας δημοσιογράφος, σύντομα την πρώτη συνέντευξη ακολούθησε η δεύτερη, κι απέκτησε έτσι ένα σχετικό στάτους.‘Ηταν γέρος πια, αλλά άξιζε τον κόπο, καθώς είδε να μαζεύονται σπίτι του νέα παιδιά που ήθελαν να μάθουν την τέχνη του. Κάθονταν δίπλα δίπλα κοντά στο παράθυρο κι αυτός από πάνω τους τους επέβλεπε ικανοποιημένος. Ναι, πολλοί από αυτούς τρελάθηκαν στην πορεία. Αλλά αυτή η δουλειά δεν ήταν για όλους.Λίγα χρόνια αργότερα είχε αποσυρθεί εντελώς και απλά καθόταν και χάζευε τον ουρανό. Καθόταν, κοιτούσε και δεν κατέγραφε. Καθόταν, κοιτούσε και δεν κατέγραφε. Μαζεύονταν σύννεφα κι αυτός τα κοιτούσε χαιρέκακα, ξέροντας πως η υποχρέωσή του απέναντί τους είχε τελειώσει. Τώρα μπορούσε να κλάψει. Αλλά δεν υπήρχε κανείς δίπλα του να καταγράψει τα δάκρυά του. Έτσι τα κράτησε μέσα του.Δεν επιτρέπεται σχολιασμός στο

Δούλευε κανονικά, με ωράριο, σε μεγάλη εταιρία, και ήταν επιφορτισμένος με το καθήκον να κάθεται στο γραφείο δίπλα στο μεγάλο παράθυρο, να κοιτάζει προς τα έξω και να σημειώνει πότε ο ουρανός πάνω από τα κεντρικά της εταιρίας ήταν εντελώς ηλιόλουστος, πότε μαζεύονταν σύννεφα, σε τι ποσοστό κάλυπταν τον ήλιο και για πόση ώρα, πότε ακριβώς ξεκίναγε και πότε ακριβώς τελείωνε η κάθε βροχή. Οι αρμοδιότητές του περιορίζονταν στη συμπλήρωση αυτών των ημερήσιων αναφορών, καθώς άλλα τμήματα ήταν επιφορτισμένα με την αρχειοθέτηση, επεξεργασία και στατιστική ανάλυσή τους. Η δουλειά του μπορεί να φαινόταν σχετικά απλή, ήταν ωστόσο σαφές πως δεν μπορούσε να την κάνει ο καθένας. Ο εταιρικός θρύλος έλεγε πως οι τρεις προκάτοχοί του στο συγκεκριμένο πόστο είχαν χάσει τα λογικά τους, καθώς η συννεφιά μπορεί απλά να σου χάλασει τη διάθεση και η λιακάδα απλά να στην φτιάξει όταν ασχολείσαι με άλλα πράγματα και ο ουρανός είναι μοναχά το φόντο. Όταν όμως η παρατήρηση του ουρανού γίνεται η κύρια απασχόλησή σου, αργά ή γρήγορα διαπιστώνεις πως υπάρχει κάτι που δεν αντέχεται στην έλευση της κάθε συννεφιάς. Εκείνος όμως ήταν φαίνεται φτιαγμένος από άλλα υλικά κι είχε έτσι διαψεύσει όλες τις προβλέψεις, έχοντας γίνει η αιτία να αλλάξουν πολλά λεφτά χέρια σε ενδοεταιρικά στοιχήματα, καθώς συμπλήρωνε ήδη ένα χρόνο, στον οποίο δεν είχε δείξει το παραμικρό σημάδι κλονισμού.Καθόταν, κοιτούσε και κατέγραφε. Καθόταν, κοιτούσε και κατέγραφε. Με ολοένα και μεγαλύτερη ακρίβεια, έχοντας αφήσει πίσω την απειρία των πρώτων μηνών. 9:32, σύννεφα πλησιάζουν από τον νότο / 9:38, συννεφιά καλύπτουσα το 10% της ατμόσφαιρας / 9:47, ουρανός εντελώς μουντός.Έμεινε στη θέση του δώδεκα χρόνια, πέντε μήνες και τέσσερεις ημέρες. Θα έμενε παραπάνω, αλλά η εταιρία άντεξε λιγότερο από αυτόν κι έκλεισε. Τον πρώτο καιρό της ανεργίας έψαξε με επιμονή για άλλη δουλειά, αλλά δεν κατάφερε να βρει τίποτα. Σιγά σιγά άρχισε να κλείνεται στο σπίτι του. Για να μη σκουριάζει, τοποθέτησε μια καρέκλα κι ένα τραπέζι δίπλα στο παράθυρο κι άρχισε να συμπληρώνει αναφορές κάθε μέρα.Καθόταν, κοιτούσε και κατέγραφε. Καθόταν, κοιτούσε και κατέγραφε. Όντας πλέον ο κύριος των αναφορών του, άρχισε να τις κολλάει στους τοίχους του σπίτιου του. Πρώτα κάλυψε το υπνοδωμάτιό του, μετά το σαλόνι, μετά ολόκληρο το σπίτι. Από τους τοίχους πέρασε στα πατώματα, μέχρι που τέλειωσαν κι αυτά. Μετά άρχισε να τις τοιχοκολλά στη γειτονιά του, ύστερα άρχισε να επεκτείνεται σε άλλες. Σίγουρα κάποιοι θα τις έβρισκαν χρήσιμες. Κι άλλωστε αυτό είχε μάθει να κάνει κι ήθελε να εξακολουθήσει να το κάνει καλά.Οι αναφορές στους τοίχους άρχισαν να κινούν την περιέργεια του κόσμου, μια μέρα τον εντόπισε ένας δημοσιογράφος, σύντομα την πρώτη συνέντευξη ακολούθησε η δεύτερη, κι απέκτησε έτσι ένα σχετικό στάτους.‘Ηταν γέρος πια, αλλά άξιζε τον κόπο, καθώς είδε να μαζεύονται σπίτι του νέα παιδιά που ήθελαν να μάθουν την τέχνη του. Κάθονταν δίπλα δίπλα κοντά στο παράθυρο κι αυτός από πάνω τους τους επέβλεπε ικανοποιημένος. Ναι, πολλοί από αυτούς τρελάθηκαν στην πορεία. Αλλά αυτή η δουλειά δεν ήταν για όλους.Λίγα χρόνια αργότερα είχε αποσυρθεί εντελώς και απλά καθόταν και χάζευε τον ουρανό. Καθόταν, κοιτούσε και δεν κατέγραφε. Καθόταν, κοιτούσε και δεν κατέγραφε. Μαζεύονταν σύννεφα κι αυτός τα κοιτούσε χαιρέκακα, ξέροντας πως η υποχρέωσή του απέναντί τους είχε τελειώσει. Τώρα μπορούσε να κλάψει. Αλλά δεν υπήρχε κανείς δίπλα του να καταγράψει τα δάκρυά του. Έτσι τα κράτησε μέσα του.Δεν επιτρέπεται σχολιασμός στοexhbtions-places-presart

Chantal Akerman: Maniac Shadows

Special event: Chantal Akerman reading

Thursday, April 11, 7pm

In conjunction with her solo exhibition Maniac Shadows, Chantal Akerman will present an evening length performative reading of a new autobiographical text, My Mother Laughs. The text details her aging mother’s daily life, intertwined with wider themes of familial relations and personal history. After the reading, attendees may preview the exhibition, opening April 12th.

Playing on entwined relationships of presence and absence, the legendary Belgian filmmaker’s latest installation features video shot at her residences in different countries. During the exhibition’s opening day, Akerman will be recorded in The Kitchen’s second-floor space reading from her story My Mother Laughs. This video will join the others, introducing a kind of psycho-geography for domestic settings at once near and far.

Curated by Tim Griffin and Lumi Tan

Exhibition Hours: Tues–Fri, 12–6pm; Sat 11–6pm

This exhibition is made possible with support from The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Dedalus Foundation, Inc., and with public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs and the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew Cuomo and the New York State Legislature.

Photo: Courtesy the artist. A memorial to nothing … Christian Boltanski’s work at the Grand Palais, Paris. Photograph: Didier PlowyFirst there is the noise, a clamour that fills the echoing vault of the Grand Palais like a great and distant crowd. It shifts as one wanders about Christian Boltanski’s Personnes, his new project for Monumenta, the annual Parisian equivalent to Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall commission. The roaring, sonorous boom of white noise separates into deep, regular thuds, and above it the croak of frogs or the alarm calls of unseen jungle birds. There are disco squelches and native drums.These sounds are all human heartbeats. Visitors can make their own contribution by having their heart rhythms recorded by white-coated technicians in booths off the main space. Boltanski, one of France’s leading artists, is compiling an archive of heartbeats that he intends to be housed, eventually, on a remote and inaccessible Japanese island. He has already collected over 15,000 individual recordings. One day, these beating hearts will all belong to the dead. If Boltanski’s art endures, one might also imagine that the visitors who make it to the island in the future have yet to be born.Boltanski’s art is filled with tragedy, humour and a sense of the absurd. It’s a hoot. It is also exceptionally cold. Monumenta usually takes place in late spring, but Boltanski delayed the opening to take advantage of lightless days and winter chill. Personnes is filled with intimations of the dead. To begin with, one is confronted by a long, high wall of stacked rusted boxes, each of them numbered, the contents of which are unknown. Beyond lies a field of old clothes, lain out in a grid running the length of the building, like municipal flower beds or a field of remembrance. There are old coats and anoraks, once-fashionable things and shapeless things, bright cardigans and children’s sweaters, tatty jumpers and forlorn skirts – a rag-picker’s field or the last day of the spring sales.Rusted vertical posts divide the grid, supporting striplights slung between wires, whose thin glare gives the space a dismal carnival air – or the feel of some stadium in which detainees have been rounded up and sent to their doom. It is hard not to think of deportations and genocides, a recurrent theme in Boltanski’s art.A great mechanical grab suspended from a crane plucks at a mountain of more old clothes, repeatedly lifting quantities of wretched sweaters, dresses and coats towards the roof of the Belle Epoque building, only to drop them again in a flurry of flailing garments and clouds of dust, back on to the 50-tonne mound. The process is as pointless as it is interminable. Boltanski has said he thinks of the grab as the indifferent hand of God, or one of those fairground amusements where you try to grab a particular toy, and always fail.Platitudes about death and absence are easy, however close to hand and present death always is. There are more people alive now than ever before. Ghosts have been crowded out and their voices drowned by the living, WG Sebald remarked somewhere. This thought also permeates Boltanski’s art, which has insistently returned to the subject not just of death but of the anonymity death confers. He deals in traces rather than ghosts, with shadows and lists, photographs of the dead and piles of old clothes. His art, ultimately, is a memorial to nothing, to everyone and no one.Another of his current projects is to be filmed in his studio, 24 hours a day, from now until his own death. There is a live feed to a cave in Tasmania owned by a collector, who can watch Boltanski’s daily life as it unfolds, but will be unable to rewind and watch prior moments of this constant record until after Boltanski himself has died. He has also said that art is an attempt to prevent death and the flight of time. Boltanski was, by his own account, a boy who never wanted to grow up.His father was a secular Jew who hid in a space under the floorboards in the family home during the last years of the Nazi occupation in Paris. Boltanski’s mother, a Christian, kept up the pretence that she had been left by her errant husband, who emerged from hiding to father the artist in 1944. This fact permeates Boltanski’s work, and he frequently refers to it in interviews; it explains his instinct for the absurd and the obsession with death.It is hard to avoid comparison between Personnes, with its unsettling atmosphere and gravitas, and the previous Monumenta project, the great Promenade by Richard Serra in 2008, one of the best works to come out of the past decade. The intentions and manners of these two artists could not be more different, but both stress the importance and place of the spectator, and their relation to objects and spaces. Both are also preoccupied by repetition and difference, a sensitivity to the conditions of place and time. It is a relationship that is grounded in the body, as much as it is in ideas. One day all our bodies will be stilled, our clothes empty.Δεν επιτρέπεται σχολιασμός στο exhbtions-places-presart

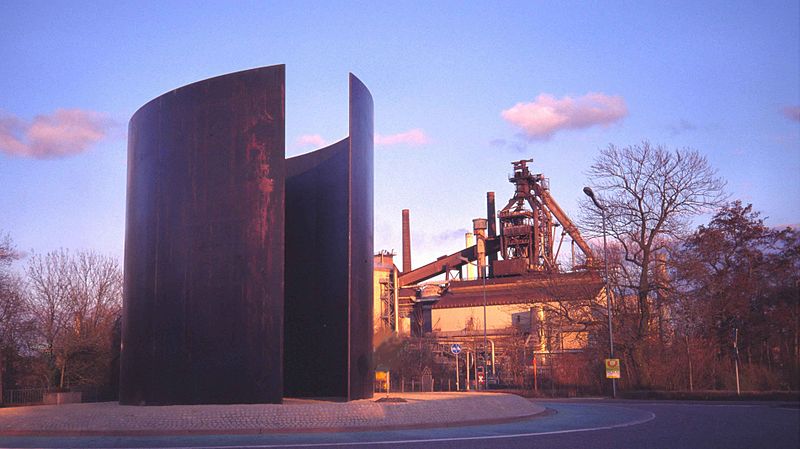

A memorial to nothing … Christian Boltanski’s work at the Grand Palais, Paris. Photograph: Didier PlowyFirst there is the noise, a clamour that fills the echoing vault of the Grand Palais like a great and distant crowd. It shifts as one wanders about Christian Boltanski’s Personnes, his new project for Monumenta, the annual Parisian equivalent to Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall commission. The roaring, sonorous boom of white noise separates into deep, regular thuds, and above it the croak of frogs or the alarm calls of unseen jungle birds. There are disco squelches and native drums.These sounds are all human heartbeats. Visitors can make their own contribution by having their heart rhythms recorded by white-coated technicians in booths off the main space. Boltanski, one of France’s leading artists, is compiling an archive of heartbeats that he intends to be housed, eventually, on a remote and inaccessible Japanese island. He has already collected over 15,000 individual recordings. One day, these beating hearts will all belong to the dead. If Boltanski’s art endures, one might also imagine that the visitors who make it to the island in the future have yet to be born.Boltanski’s art is filled with tragedy, humour and a sense of the absurd. It’s a hoot. It is also exceptionally cold. Monumenta usually takes place in late spring, but Boltanski delayed the opening to take advantage of lightless days and winter chill. Personnes is filled with intimations of the dead. To begin with, one is confronted by a long, high wall of stacked rusted boxes, each of them numbered, the contents of which are unknown. Beyond lies a field of old clothes, lain out in a grid running the length of the building, like municipal flower beds or a field of remembrance. There are old coats and anoraks, once-fashionable things and shapeless things, bright cardigans and children’s sweaters, tatty jumpers and forlorn skirts – a rag-picker’s field or the last day of the spring sales.Rusted vertical posts divide the grid, supporting striplights slung between wires, whose thin glare gives the space a dismal carnival air – or the feel of some stadium in which detainees have been rounded up and sent to their doom. It is hard not to think of deportations and genocides, a recurrent theme in Boltanski’s art.A great mechanical grab suspended from a crane plucks at a mountain of more old clothes, repeatedly lifting quantities of wretched sweaters, dresses and coats towards the roof of the Belle Epoque building, only to drop them again in a flurry of flailing garments and clouds of dust, back on to the 50-tonne mound. The process is as pointless as it is interminable. Boltanski has said he thinks of the grab as the indifferent hand of God, or one of those fairground amusements where you try to grab a particular toy, and always fail.Platitudes about death and absence are easy, however close to hand and present death always is. There are more people alive now than ever before. Ghosts have been crowded out and their voices drowned by the living, WG Sebald remarked somewhere. This thought also permeates Boltanski’s art, which has insistently returned to the subject not just of death but of the anonymity death confers. He deals in traces rather than ghosts, with shadows and lists, photographs of the dead and piles of old clothes. His art, ultimately, is a memorial to nothing, to everyone and no one.Another of his current projects is to be filmed in his studio, 24 hours a day, from now until his own death. There is a live feed to a cave in Tasmania owned by a collector, who can watch Boltanski’s daily life as it unfolds, but will be unable to rewind and watch prior moments of this constant record until after Boltanski himself has died. He has also said that art is an attempt to prevent death and the flight of time. Boltanski was, by his own account, a boy who never wanted to grow up.His father was a secular Jew who hid in a space under the floorboards in the family home during the last years of the Nazi occupation in Paris. Boltanski’s mother, a Christian, kept up the pretence that she had been left by her errant husband, who emerged from hiding to father the artist in 1944. This fact permeates Boltanski’s work, and he frequently refers to it in interviews; it explains his instinct for the absurd and the obsession with death.It is hard to avoid comparison between Personnes, with its unsettling atmosphere and gravitas, and the previous Monumenta project, the great Promenade by Richard Serra in 2008, one of the best works to come out of the past decade. The intentions and manners of these two artists could not be more different, but both stress the importance and place of the spectator, and their relation to objects and spaces. Both are also preoccupied by repetition and difference, a sensitivity to the conditions of place and time. It is a relationship that is grounded in the body, as much as it is in ideas. One day all our bodies will be stilled, our clothes empty.Δεν επιτρέπεται σχολιασμός στο exhbtions-places-presart3dimensions-iun-lgt-park-public sculpture-outopia-eliason-le corbusier-boltanski// sem 3,4 public sculpture 1,2

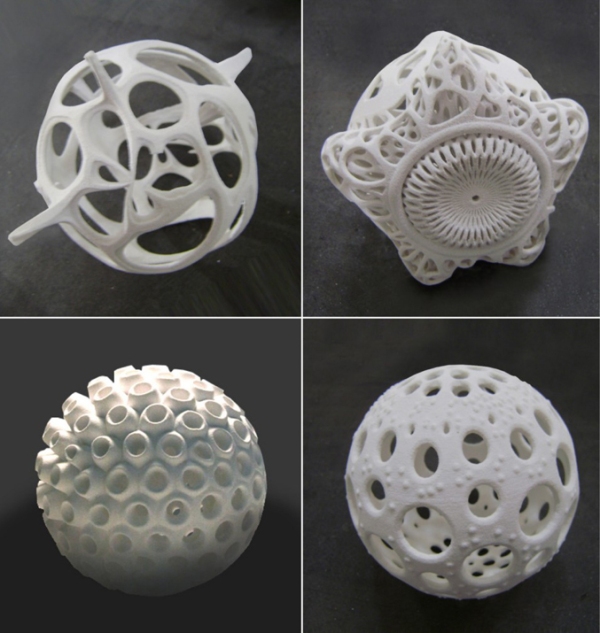

24 Spheres. Time of Change.

makro

pbscl

public sculpture- scale- primitive shapes- the magic of material

0

0

24 Spheres. Time of Change.

mikro Mya-3dprt-3dim-3dmax-rl-mod

24 Spheres. Time of Change.

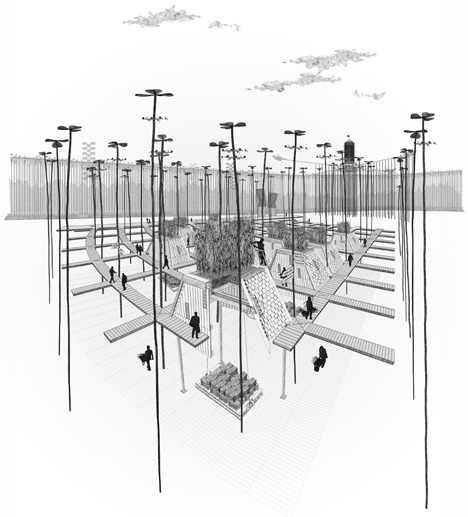

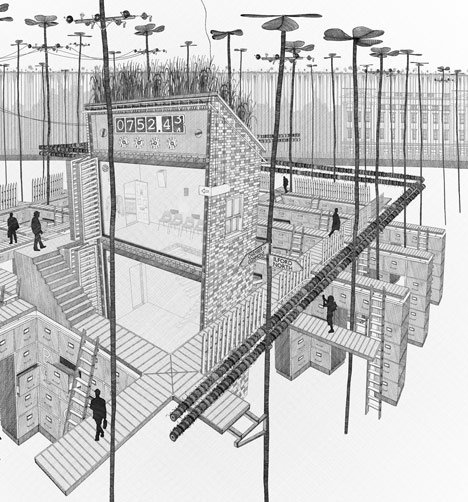

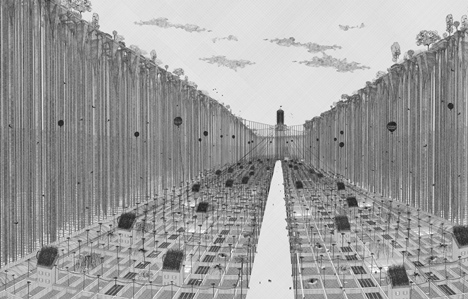

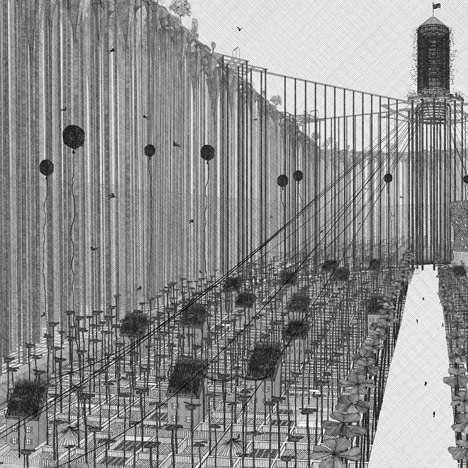

For me Utopia is tied to our ‘now’, to the moment between one second and the next. It constitutes a potential that is actualized and transformed into reality; an opening where concepts such as subject and object, inside and outside, proximity and distance are thrown up in the air only to be defined anew. Our sense of orientation is challenged, and the coordinates of our spaces,collective and personal, have to be renegotiated. Mutability and motion lie at the core of Utopia.” – Olafur EliassonAs visitors step into long tunnel filled with dense fog and slowly shifting colored lights, they must give up their sense of sight in order to pass from one end to the next in this 2010 installation by Olafur Eliasson at the ARKEN museum in Copenhagen. The dense fog instead encourages visitors to rely on their other senses to navigate the space, drawing to their attention changes in light and sound as other visitors move around you. The colored lights change subtly, from the bright yellows of morning to the deep inky purples and blues of twilight, allowing participants to notice the changes in light of everyday that they might otherwise miss with the distractions of the outside world present. Concentrating on our personal relation to the world around us, Eliasson seeks to reveal the idea of ‘Utopia’ to us as “the now”, or as “moments between one second and the next”. A sensory experience. His 90 meter installation challenges visitors to consider their place in their environment and how they relate to not only the world around them, but also others who share the same space. By blocking outside distractions with the fog, we can better understand our own Utopia, redefining our identity in relation to our surroundings.Eliasson’s use of the visitor as a participant in the work is more than just a cheap thrill, instead the slow pace of the trek through the tunnel encourages quiet reflection and promotes both inner and outer awareness of the world and our place in it. (2)Δεν επιτρέπεται σχολιασμός στο 3dimensions-iun-lgt-park-public sculpture-outopia-eliason-le corbusier-boltanski// sem 3,4 public sculpture 1,2Architectures without Place [diaporama]

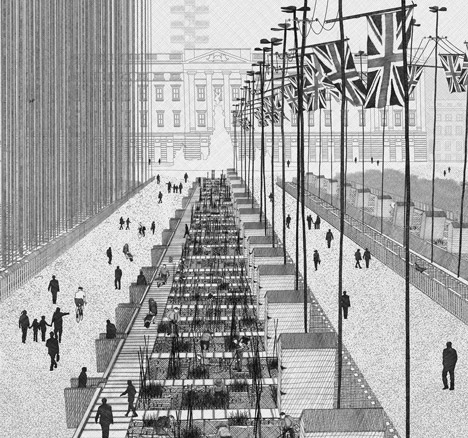

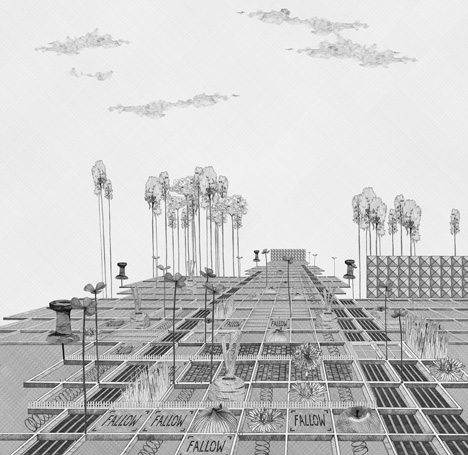

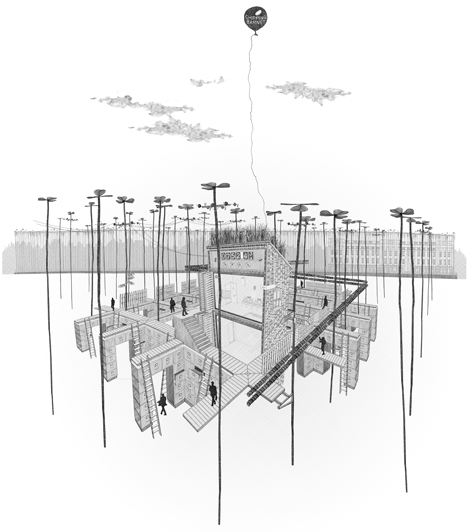

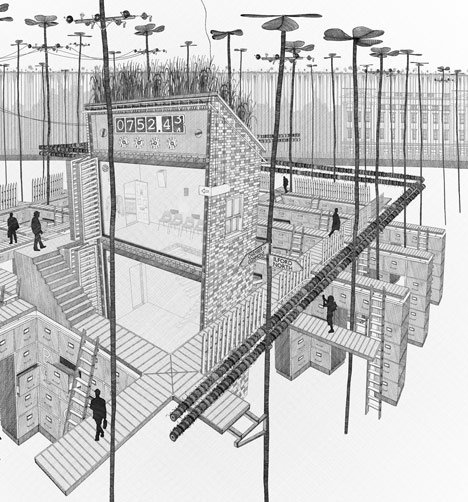

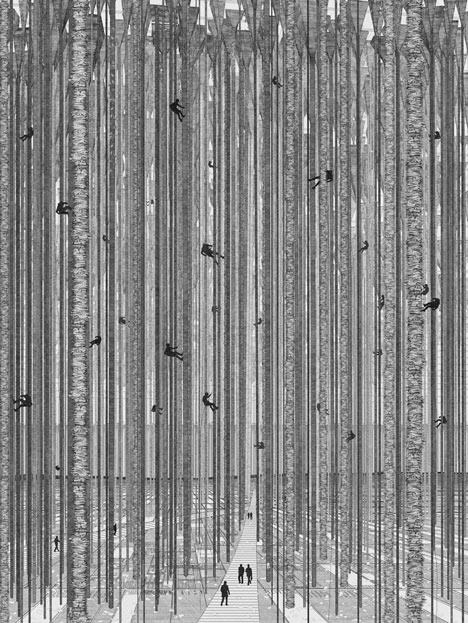

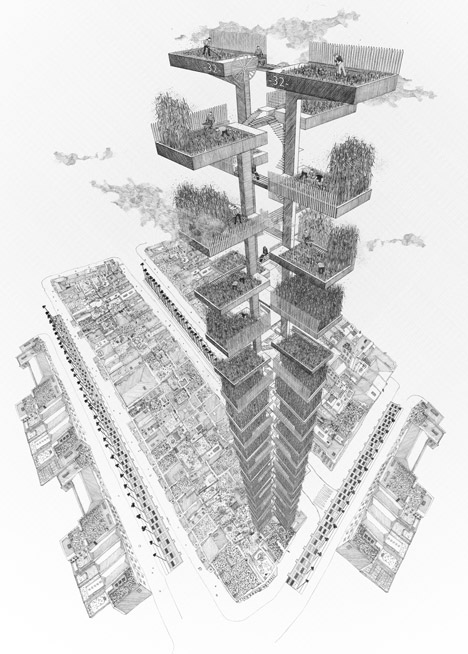

Architectures without Place [diaporama]

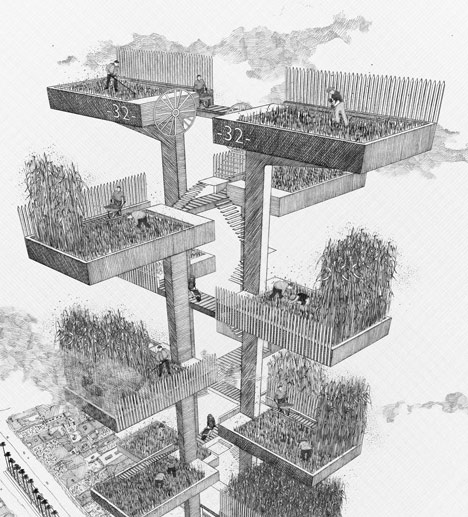

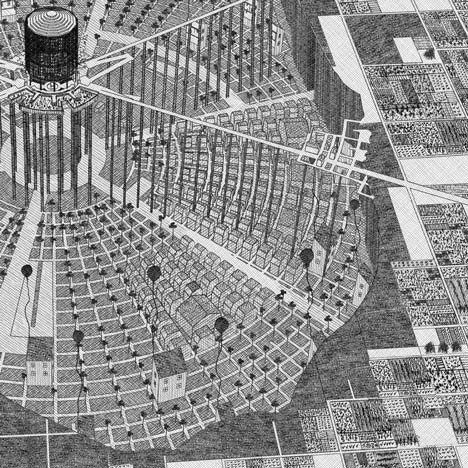

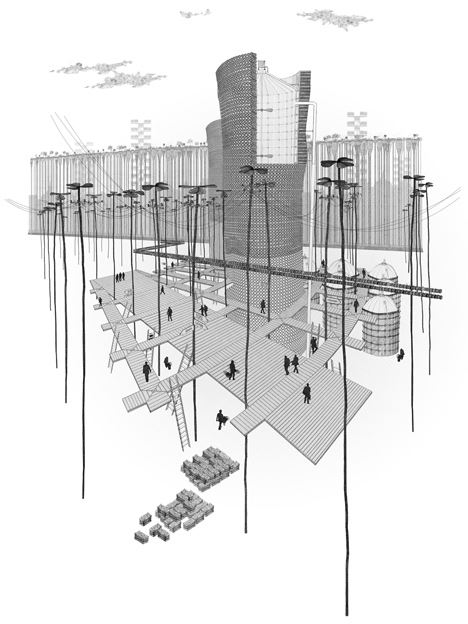

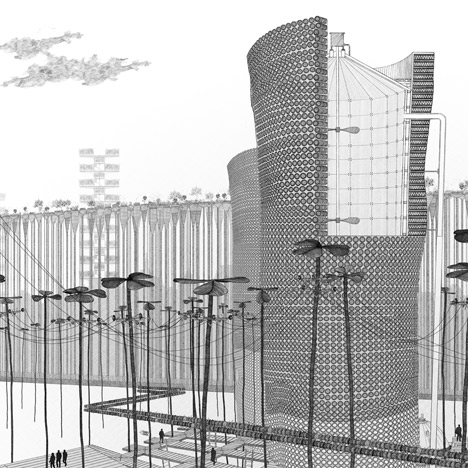

Construccions al bosc d’Olot by Josep Pujiula [1974]As in the rest of Spain, Catalonian history is marked for the General Franco’s dictatorship from 1939 to 1975. The Franco era was characterised by repression of pro-democracy and left-wing organisations. In the middle of the repression, the post-war years led Catalonia to an economical growth which started in 1959 and, according to the Museo d’Història de Catalunya, “led [Catalonia] to major economic and social changes: foreign capital came into the country; industry diversified; tourism developed; waves of immigration from within Spain occurred; and the consumer society became established.“Within this context, it is interesting to discover some of the projects presented on the exhibition and publication Architectures without Place, which analyzes a particular vision of architectural production in Catalonia since 1968. As if we were talking about other phantom city, the aim of the exhibition was to limit the study to architectures that do not physically exist but nonetheless help us to understand the present-day reality in all its complexity. As we can read on the exhibition web-site:The great majority are ideal projects that never got off the architect’s drawing board. Others are projects that have changed as a result of being altered or demolished, or are ephemeral architecture projects conceived for a brief existence: among these, set designs form a group apart by virtue of their specific logic and clearly differentiated conditioning factors.There are many facts to think about, as how any dictatorship affects architecture and culture in general terms or how the economical limitations have been the seed for creativity and multidisciplinarity on those years, when architectures were proposed or imagined by creative talents from other disciplines such as film, the visual arts and especially the comic.

Modern Iconography. América Sánchez [1980]Housing was not the exemption. While architects and artist were dreaming on a better and free world, the economic growth that started in those years has affected the architectural production, with the use of new materials and communication tools that allowed architects to know what was happening abroad in the architectural arena. Some historical facts such as the promulgation of the Stabilisation Plan [a plan to cut inflation and reduce the balance of payments] in July 1959, when the régime abandoned the despotic interventionist approach that it had maintained since 1939, had influenced the ideals of architects and creative minds that lived in Catalonia. Again from the Museo d’Història de CatalunyaThis [economical] expansion took place without any type of urban planning nor the slightest degree of democratic control over the economy. Urban chaos and the lack of a basic infrastructure were common in the large cities and the tourist areas on the coast.On those years, homes underwent major changes: New materials, such as chipboard and Formica, revolutionised furniture making. The flood of new domestic appliances continued unabated, and residents’ comfort was dramatically improved by electric fridges, washing machines, dishwashers, radios and televisions, as we can see in the following project:

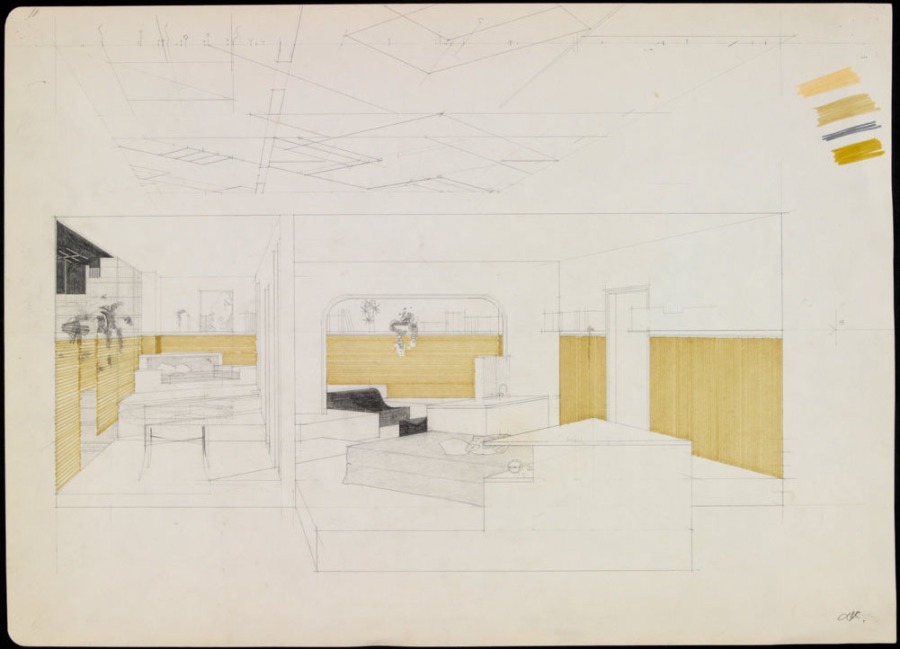

Reforma apartament Stéphanie. Lluís Clotet and Òscar Tusquets [Studio PER, 1974-79]

Reforma apartament Stéphanie. Lluís Clotet and Òscar Tusquets [Studio PER, 1974-79]After this brief historical reflection, here is a [diaporama] with some architectures proposed or imagined in which the discussion about the city is carried out from a perspective that, remote from the particular servitudes of the architecture profession, often gives it a greater lucidity.

Naus industrials Josep Ignasi Llorens and Alfons Soldevila [1980]

Infatables. Josep Ponsatí [1971]

Club de golf a Sant Cugat del Vallès. MBM Arquitectes [1970]

Carretera de les aigües. Emili Donato [1981]

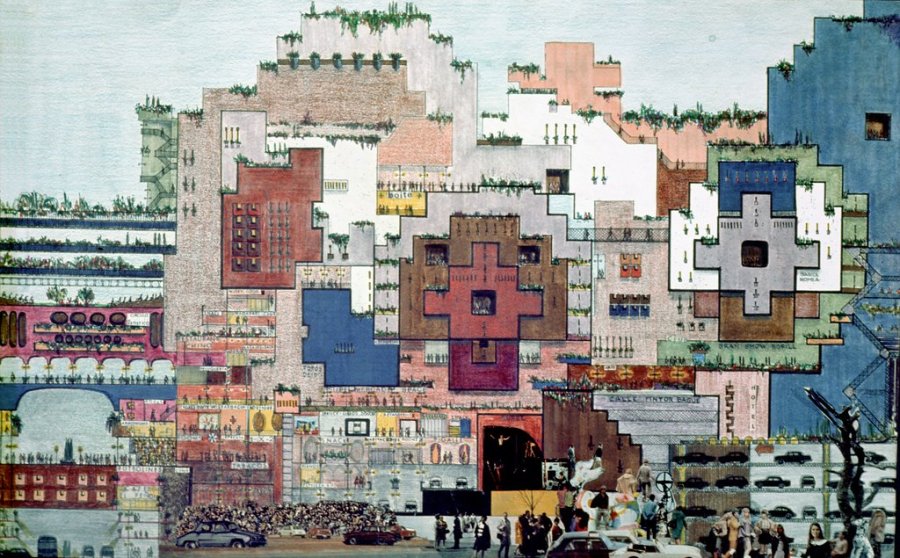

City in Space. Ricardo Bofill, Taller de Arquitectura [1968]The exhibition was designed with a non-chronological narrative of events which aimed to offer a more reflective and multifaceted reading of the content, providing us with the elements for a debate on the role of architecture and its interaction with the socio-political context. General Franco died on 20 November 1975 and the opening up of the regime led to democracy by another route, political reform. In June 1977, the first free elections since 1936 were held. This socio-political changes drives us to reflect on the paradigm of the relationship between the architect and society.We want to finish with the thought that architecture and architectural communication has often been related with activism in the political context, using image and media as political manifestos. As Beatriz Colominatold us in an interview, “you have to think that in the decade of the 1970s, the political agenda was almost part of our architectural curriculum.” And she adds:I think that we are facing a very interesting era, because architecture always develops in a deeper way in moments of crisis. In the decade of the 60s and 70s, we had the oil crisis, the war, and other conflicts and we had the time to think about ecology, emergency housing, new materials, the space program, etc. And now that we are living in a similar state of the world, we can discover again some similar responses and recover the principles that we have lost.Utopias as activism and polemical reaction, keep on going. In the current years, when Barcelona is facing a “star-architect-fever” on its architectural development, Beth Galí reflects this political and economical situation in Catalonia with her project La Sagrera Família [also included in the exhibition], a paper-architecture project aimed to condemn the mediatization of a monument like Gaudi’s Sagrada Familia:

La Sagrera Família, Barcelona. Beth Galí [2000]But is it Architecture?* | Beniamino Servino

I’m an ephemeral and not too discontented citizen of a metropolis thought to be modern because all known taste has been avoided in the furnishing and exterior of houses as well as the city plan. Here you cannot point out a trace of a single monument to superstition. Morals and language are reduced to their simplest expression, in short! These millions not needing to know each other pursue their education, work, and old age so identically that the course of their lives must be several times shorter than absurd statistics allow this continent’s people. So, from my window, I see fresh spectres roaming through thick eternal fumes – our woodland shade, our summer night! – New Furies, before my cottage which is my homeland, my whole heart, since all here resembles this – Death without tears, our active daughter and servant, desperate Love and pretty Crime whimpering in the mud of the street.

Δεν επιτρέπεται σχολιασμός στο Architectures without Place [diaporama]music-tradition

http://www.ert.gr/webtv/et1/item/11801-Moysikh-paradosh-A%CE%84Meros-20-03-2013#.UUr5jxcaOaZHISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE The Shiraz Arts Festival: Western Avant-Garde Arts in 1970s Iran Robert Gluck

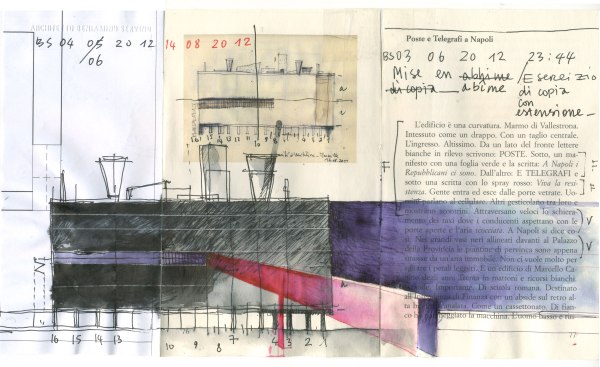

iannis xenakis proposal at shah pahlavi;s reign

During the twilight years of Mohammed Reza Shah Pahlavi’s reign in Iran, a panoply of avant-garde forms of expression complemented the rich, 2,500-year history of traditional Persian arts. Renowned musicians, dancers and filmmakers from abroad performed alongside their Persian

peers at the annual international Shiraz Arts Festival. Elaborate plans were developed for a significant arts center that was to include sound studios and work spaces for residencies.

Young Iranian composers and artists were inspired by the festival to expand their horizons to integrate contemporary techniques and aesthetics. Some subsequently traveled abroad for

further study. Although the 1979 Islamic Revolution marked the end of institutions sustaining the avant-garde and scholarships for international study, creative expression sparked by

the festival has continued in cinema and other arts. FOUNDING OF THE SHIRAZ ARTS FESTIVAL

A central goal of Pahlavi rule throughout the 20th century was modernization and industrialization, while still maintaining independence from other nations, particularly Great Britain

and the Soviet Union [1]. Mohammed Reza Shah Pahlavi hoped to ground his independence and authority in three assertions: secular rule, Pahlavi political hegemony and continuity with the ancient, pre-Islamic Persian Empire. In 1967, the Shah crowned himself Emperor and his wife Empress, thereby securing her right of succession. The upcoming 2,500th anniversary (1971) of the conquest of Babylonia by Cyrus the Great, the founder of the Persian empire, provided

a rationale for an international cultural event at the ruins of Persepolis, the ancient pre-Islamic royal seat.

The Shiraz Arts Festival began in 1967 as a showcase for the royal court, especially Empress Farah Diba, a former architectural student, who convened each year’s events. Musician

Gordon Mumma remembers her as “an extraordinary woman

of considerable worldly knowledge” [2]. National Iranian Radio and Television (NIRT), also founded in 1967, served as festival sponsor. Sharazad (Afshar) Ghotbi, a violinist and wife of

NIRT director Reza Ghotbi, was named musical director. Programming reflected Empress Farah’s Western-leaning, contemporary tastes (Fig. 1).

The decision to establish a festival that presented Western-oriented

arts was fraught with potential con- flict. Iran boasted of openness to intellectual ideas and the social integration of women, but the state sharply curtailed internal political

expression, unwittingly fostering the growth of a radical Islamic clerical opposition who would prove to be offended by festival programming. The opulence of the court was on full display throughout the 11 years of events, highlighting the economic distress of the general

populace. Nonetheless, the creative activity featured at the festival reflected the most forward-looking international efforts, presenting Iran to the world as pioneering and open.

EXPERIENCES OF WESTERN=-PERFORMERS AND ATTENDEES

For visiting artists, the Shiraz Arts Festival offered a remarkable experience. Merce Cunningham Dance Company (MCDC) dancers Carolyn Brown and Valda Setterfield recall

their 1972 visit as a “unique . . . wonderful unforgettable adventure” [3] and as “heady and thrilling” [4]. Gordon MummaABSTRACT

Iran in the 1970s was host to an array of electronic music and avant-garde arts. In the

decade prior to the Islamic revolution, the Shiraz Arts Festival provided a showcase

for composers, performers, dancers and theater directors from Iran and abroad, among

them Iannis Xenakis, Peter Brook, John Cage, Gordon

Mumma, David Tudor, Karlheinz Stockhausen and Merce Cunningham. A significant arts

center, which was to include electronic music and recording studios, was planned as an

outgrowth of the festival. While the complex politics of the Shah’s regime and the approaching revolution brought these developments to an end, a younger generation of artists

continued the festival’s legacy.GLOBAL CROSSINGS

Article Frontispiece.

Valda Setterfield of the Merce Cunningham

Dance Company in a 1968 performance of Rainforest with Andy

Warhol–designed pillows. Rainforest, with the same pillows, was

performed as part of Shiraz Event at the Shiraz Arts Festival in

1972. (Photo courtesy James Klosky)

Fig. 1. Empress Farah greets John Cage and Merce Cunningham

at the 1972 festival. (Photo courtesy of Cunningham Dance

Foundation Archive)calls it “one of the most extraordinary cultural experiences of my life.” Setterfield’s

memories of Shiraz include:

drinking watermelon juice for breakfast,

huge insects buzzing around and drowning in the swimming pool, the heat of the

ground being too much to walk to the

pool without shoes. The nearby market

was wonderful, filled with the sound of

metal pots being beaten into shape and

mysterious things to eat. When the sun

went down, everything smelled like roses.

An elite audience converged on the

festival. Mumma points out that “the cost

of admission was not only money, but also

security clearance.” A 1976 column in

Tehran Journal mixed criticism and gossip: “the Empress [appeared] in a multicolored velvet siren suit that quite

outshone most of the ladies’ gowns” [5].

Brown recalls that the audience “appeared far more interested in looking at

the Queen and her entourage than at the

dancing,” but Mumma found the audience to be serious and interested: “There

were none of the aggressive arguments

about ‘that isn’t music’ stuff that we often

encountered elsewhere.”

Security was tight, as Mumma notes:

“In Persepolis each of us was given a

‘guide’ (read ‘guard’) dressed in a Western suit with a tie and jacket. The primary jacket function was to conceal their

weapons. . . . We traveled in Iranian military aircraft.” Setterfield remembers:

sented Nuits, a choral work dedicated

to political prisoners, some named and

“thousands of forgotten ones whose

names are lost” [8], and in 1969 presented the percussion work Persephassa,

commissioned by the festival and Office

de Radiodiffusion Télévision Française

(ORTF). Persephassa links cross-cultural

legends of the Greek goddess Persephone. Xenakis’s third and final work for

the festival was the commissioned multimedia extravaganza Polytope de Persépolis,

which premiered at the Persepolis ruins

on 26 August 1971. Xenakis describes the

work as

visual symbolism, parallel to and dominated by sound . . . correspond[ing] to a

rock tablet on which hieroglyphic or

cuneiform messages are engraved. . . .

The history of Iran, fragment of the world’s history, is thus elliptically and abstractly represented by means of clashes, explosions, continuities and underground currents of sound [8].

Critic James Harley describes Polytope de Persépolis as“unrelenting in its density

and continuously evolving architecture”

[9].Xenakis scholar Sharon Kanach reconstructs the scene as follows:

The audience was placed in the ruins of Darius’s Palace and was able to move

freely between the six listening stations placed within these ruins. Each station

had eight speakers, one for each track. . . . The one-hour spectacle began in total

darkness with a “geological prelude” of excerpts from Xenakis’s first electroacoustic work, Diamorphoses (1957). Immediately afterwards, on the mountain facing the site, two gigantic bonfires are lit, projector lights sweep the night sky, and two red laser beams scan the ruins.

Then, several groups of children appear carrying torches and proceed to climb to

the summit, towards the bonfires, outlining in scintillating light the mountain’s

crest. . . . Suddenly, the groups of children disperse and climb down the mountain

in constellation-like figures (Color Plate E) and finally congregate between the

two tombs where their torches spell out in Persian “we bear the light of the

earth,” a phrase by Xenakis. One last outburst and the 150 torch-bearers run past

the ravine and disappear through the crowd into the forest [10].

The new work faced mixed reactions. The Empress and NIRT liked it enough

to offer Xenakis a further commission for the design of a proposed art center. However, some Iranian critics, sensitive to the legacy of Western hegemony in Iran, associated Greek composer Xenakis’s torch spectacle with the burning of Persepolis

by Alexander the Great [11] or suggested that the symbolism could be interpreted

as the actions of Nazi brownshirts [12].“Persepolis was absolutely filled with soldiers with rifles. They seemed to appear

out of the woodwork at every corner.

There was a real sense of wariness and

danger. You looked at something extraordinary, old and beautiful, and suddenly you would see the soldiers.” Merce

Cunningham discovered that pillows

used in the Persepolis performance

“were in a room full of machine guns”

[6].

PROGRAMMING

The Shiraz Arts Festival always include traditional music from around the world.

The 1967–1970 programming included

Indian sitarist Ustad Vilayat Khan, American violinist Yehudi Menuhin, numerous Persian classical musicians and artists, a Balinese gamelan ensemble, the Senegalese National Ballet and performances of the Persian passion play ta’ziyeh

(“mourning” or “consolation”) portraying the founding of Shi’a Islam [7].

Ta’ziyeh, banned under the Shah’s father,

influenced avant-garde Western theatrical directors Peter Brook, Jerzy Grotowski

and Joseph Chaikin (who brought The

Open Theatre [Fig. 2]). Visiting dance

companies included Merce Cunningham

in 1972 and Maurice Bejart in 1976.

The Western composer most closely

associated with the Shiraz Arts Festival

was Iannis Xenakis, who in 1968 pre-

22 Gluck, The Shiraz Arts Festival

GLOBAL CROSSINGS

Fig. 2. Performance of Joseph Chaikin’s Open Theater at the 1971

Shiraz Arts Festival. Still image taken from a Pars Video documentary.Xenakis (Fig. 3) responded that “fire

and light represented goodness and

eternal life . . . using children today as

torch-bearers, representing the men and

women of tomorrow, is a cry of hope for

the future” [13].

The 1972 festival was a veritable Stockhausen festival, the composer’s “highlight of the year” [14], featuring three

“intuitive” compositions and Gruppen,

Carre, Stimmung, Gesang der Jünglinge, Telemusik, Prozession, Kontakte, Spiral, several

Klavierstücke, Hymnen (Fig. 4) and Mikrophonie I. MCDC dancer Brown describes

Stockhausen’s appearance at the festival as like that of a “guru . . . walking the

streets of Shiraz white robed.” The festival closed with an outdoors performance

of Sternklang, in which

a seething mass of about eight thousand

poured up the star-shaped converging

paths. . .the spectators squashed together

on the pathways, besieging the performers . . . [some] clambered up the loudspeaker scaffolding and were hauled

down again by the police . . . Stockhausen

was convinced that his music would calm

the listeners. And so it was. After half an

hour of music the waves subsided [15].

Tehran Journal described the 1972 festival as “the most avant-garde and most

controversial Shiraz Festival so far” [16].

Electronic music dominated the offerings, which included numerous concerts

by Stockhausen, performances by MCDC

featuring musicians John Cage, David Tudor and Gordon Mumma, and tradiwas helium-filled pillows designed by

Andy Warhol (Article Frontispiece), tethered to the ancient pillars, as Mumma recalls, to “keep them from floating away

from the performance.” Company administrator Jean Rigg remembers that

“The winds came up, and many simply

snapped their lines and floated off . . . the

effect was great” [21].

The musical concert included

Mumma’s Ambivex (“a composition for

trumpet [or cornet] with live cybersonic

modification”) and a simultaneous performance of Cage’s Birdcage and Tudor’s

Monobird (Fig. 6) [22]. Birdcage (1972)

is a “complex, exuberant, and joyful” collage composed from sounds of birds,

“Cage singing his ‘Mureau’ and . . . ambient sounds” [23].

IMPACT ON YOUNG

COMPOSERS AND ARTISTS

The festivals proved influential on the rising generation of Iranian artists and composers. Brown recalls: “John Cage was

greeted by many devoted fans as a muchloved ‘hero.’” Students at Tehran University, such as Persian-American composer

Dariush Dolat-shahi, experienced the festival close up because the music department was actively involved in the events.

Dolat-shahi recalls that “Every year, I

waited for the event to happen. These festivals were a major source of information

for us about what was happening musically outside Iran. I received my own first

commission when I was nineteen years

old” [24].

Dolat-shahi became “part of a group

of four people who used to get together

and listen to modern music including

Schoenberg, Berg, Ligeti,” and realized

his first work for strings and tape, popular instrumentation during the festivals, using a small tape recorder. Festival

performances also influenced the development of Iranian theater, as IranianAmerican writer and theater artist Zara

Houshmand observes about a recent

Tehran performance directed by Majid

Jafari: “Jafari’s work, like that of Pessyani

and so many Iranian directors, owes

a huge debt to Jerzy Grotowski, Peter

Brook, Tadeusz Kantor, and other leading lights of the European avant-garde

who accepted invitations to the Shiraz