computer animation

+ 2 link απο το site του TED [http://www.ted.com/talks/mark_pagel_how_language_transformed_humanity.html]

[http://www.ted.com/talks/deb_roy_the_birth_of_a_word.html]

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rlATVg0D43w]

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rlATVg0D43w]

4.301 Introduction to Visual Arts

Assignment: Shaping Time

Using demonstrated production and editing techniques, make a 90 second experimental video.

Sound must be diegetic or self generated.

This unit asks you to express emotional qualities of your choice by creating a rhythm and/or

procession of events through editing. Use as material for your video your physical self in space,

possibly in relation to objects, props, processes or movements.

Exercises:

Make (2) one minute videos: one in which time appears to be moving quickly, the other in which

time appears to be moving slowly. (Consider using a tripod.)

Remix: Using a provided film clip, make a one minute video edited to convey an emotive quality

not ordinarily associated with the clip.

Reading:

Brand, Stewart, The Clock of the Long Now

Viola, Bill, “The Porcupine and the Car” and “I Do Not Know What It Is I Am Like”, Reasons for

Knocking at an Empty House

Gaensheimer, Susanne, “Moments in Time”, On Slowness, Lenbachhaus München

4.301 Introduction to Visual Arts

Assignment:Body Extension

Create an art work that exists as a “body extension,” a sculptural/architectural/corporeal supplement. Use your own body as a starting point for an exploration of the self, including psychological and physical aspects and concepts of identity. The second part of the assignment asks you to interact with your body extension in a way that significantly alters your experience of it. Your interaction can be represented by video documentation, or by live performance.

Exercises:

–

Bring in images that illustrate the concept of existing “body extensions.”

–

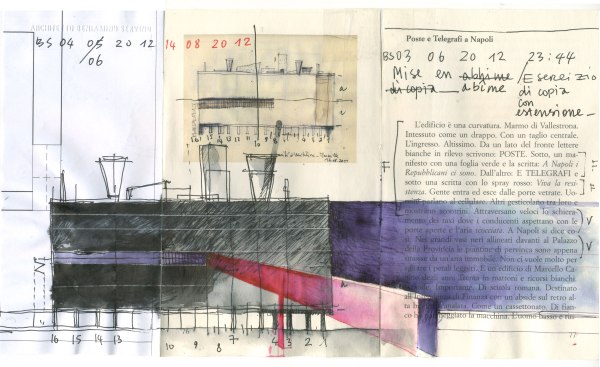

Use any appropriate means to visually represent an aspect of your body experience such as an inner emotional, physical or sensory process. Do not explain what you know about it, but what you experience, do not use language. Notation methods can include drawing, diagrams, collage, etc..

Readings: Horn, Rebecca and Celant, Germano, “The Bastille Interviews.” Rebecca Horn, 1993 Linker, Kate, “On Language and Its Ruses: Poetry into Performance.” Vito Acconci, 1994 Pejic, Bojana, “Being-in-the-Body, On the Spiritual in Marina Abramovic’s Art.” Abramovic, 1993

https://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=endscreen&v=sk4qxfrBE6w&NR=1

plnes grvyrd-net-pnt

This sublime adventure fantasy, replete with proto-steampunk imagery, touchingly conveys a message of ecological awareness. A young girl drops from the sky and lands in the arms of orphan Pazu—and not a moment later they’re on the run from a shadowy government agency and a band of pirates, both after the magic crystal she possesses. The chase leads them up and into the clouds to the floating airship Laputa, an overgrown fortress inhabited by gargantuan, dilapidated robots.

http://www.youtube-nocookie.com/embed/McM0_YHDm5A

The film tells the story of Chronos, the personification of time and the inability to realize his desire to love for a mortal. The scenes blend a series of surreal paintings of Dali with dancing and metamorphosis. The target production began in 1945, 58 years before its completion and was a collaboration between Walt Disney and the Spanish surrealist painter, Salvador Dalí. Salvador Dali and Walt Disney Destiny was produced by Dali and John Hench for 8 months between 1945 and 1946. Dali, at the time, Hench described as a “ghostly figure” who knew better than Dali or the secrets of the Disney film. For some time, the project remained a secret. The work of painter Salvador Dali was to prepare a six-minute sequence combining animation with live dancers and special effects for a movie in the same format of “Fantasia.” Dali in the studio working on The Disney characters are fighting against time, the giant sundial that emerges from the great stone face of Jupiter and that determines the fate of all human novels. Dalí and Hench were creating a new animation technique, the cinematic equivalent of “paranoid critique” of Dali. Method inspired by the work of Freud on the subconscious and the inclusion of hidden and double images.

Dalí said: “Entertainment highlights the art, its possibilities are endless.” The plot of the film was described by. Dalí as “A magical display of the problem of life in the labyrinth of time.”

Walt Disney said it was “A simple story about a young girl in search of true love.”

http://www.youtube-nocookie.com/embed/1GFkN4deuZU

>>παραδοξότητα και παραλογισμός.

“animation” –

“the act of producing ‘moving pictures’;

the technique, by means of which movement is given,

on film, to a series of drawings

(esp. for an animated cartoon)”

Διαδραστική σύνθεση εικόνας σε πραγματικό χρόνο

Ήχος

uowm ftp server //

non-normative.

text/html MIME type, then it will be processed as an HTML document by Web browsers. This specification defines the latest HTML syntax, known simply as “HTML”.application/xhtml+xml, then it is treated as an XML document by Web browsers, to be parsed by an XML processor. Authors are reminded that the processing for XML and HTML differs; in particular, even minor syntax errors will prevent a document labeled as XML from being rendered fully, whereas they would be ignored in the HTML syntax. This specification defines the latest XHTML syntax, known simply as “XHTML”.noscript feature can be represented using the HTML syntax, but cannot be represented with the DOM or in the XHTML syntax. Comments that contain the string “-->” can only be represented in the DOM, not in the HTML and XHTML syntaxes.αρχικό παράδειγμα γραφής dom html

A document with a short head

...

An application with a long head

http://support.js

...

ex

|

|

The theory of mass culture-or mass audience culture, commercial culture, “popular”

culture, the culture industry, as it is variously known-has always tended to define its object

against so-called high culture without reflecting on the objective status of this opposition.

As so often, positions in this field reduce themselves to two mirror-images, and are

essentially staged in terms of value. Thus the familiar motif of elitism argues for the priority

of mass culture on the grounds of the sheer numbers of people exposed to it; the pursuit of

high or hermetic culture is then stigmatized as a status hobby of small groups of

intellectuals. As its anti-intellectual thrust suggests, this essentially negative position has

little theoretical content but clearly responds to a deeply rooted conviction in American

radicalism and articulates a widely based sense that high culture is an establishment

phenomenon, irredeemably tainted by its association with institutions, in particular with

the university. The value invoked is therefore a social one: it would be preferable to deal

with tv programs, The Godfather, orJaws, rather than with Wallace Stevens or HenryJames,

because the former clearly speak a cultural language meaningful to far wider strata of the

population than what is socially represented by intellectuals. Radicals are however also

intellectuals, so that this position has suspicious overtones of the guilt trip; meanwhile it

overlooks the anti-social and critical, negative (although generally not revolutionary)

stance of much of the most important forms of modem art; finally, it offers no method for

reading even those cultural objects it valorizes and has had little of interest to say about

their content

**html

Presentation related attributes

background (Deprecated. use CSS instead.) and bgcolor (Deprecated. use CSS instead.) attributes for body (required element according to the W3C.) element.align (Deprecated. use CSS instead.) attribute on div, form, paragraph (p) and heading (h1…h6) elementsalign (Deprecated. use CSS instead.), noshade (Deprecated. use CSS instead.), size (Deprecated. use CSS instead.) and width (Deprecated. use CSS instead.) attributes on hr elementalign (Deprecated. use CSS instead.), border, vspace and hspace attributes on img and object (caution: the object element is only supported in Internet Explorer (from the major browsers)) elementsalign (Deprecated. use CSS instead.) attribute on legend and caption elementsalign (Deprecated. use CSS instead.) and bgcolor (Deprecated. use CSS instead.) on table elementnowrap (Obsolete), bgcolor (Deprecated. use CSS instead.), width, height on td and th elementsbgcolor (Deprecated. use CSS instead.) attribute on tr elementclear (Obsolete) attribute on br elementcompact attribute on dl, dir and menu elementstype (Deprecated. use CSS instead.), compact (Deprecated. use CSS instead.) and start (Deprecated. use CSS instead.) attributes on ol and ulelementstype and value attributes on li elementwidth attribute on pre elementHTML is written in the form of HTML elements consisting of tags enclosed in angle brackets (like ), within the web page content. HTML tags most commonly come in pairs like

, although some tags, known as empty elements, are unpaired, for example

Sample page

Sample page

This is a simple sample.

Screen object. [MQ] [CSSOMVIEW]

Sample page

Sample page

This is a simple sample.

This is very wrong!

This is correct.

a element and itshref attribute:simple

=” character. The attribute value can remainunquoted if it doesn’t contain space characters or any of " ' ` = < or >. Otherwise, it has to be quoted using either single or double quotes. The value, along with the “=” character, can be omitted altogether if the value is the empty string.DocumentType node, Element nodes, Text nodes, Comment nodes, and in some cases ProcessingInstruction nodes.htmlhtml

html element, which is the element always found at the root of HTML documents. It contains two elements,head and body, as well as a Text node between them.Text nodes in the DOM tree than one would initially expect, because the source contains a number of spaces (represented here by “␣”) and line breaks (“⏎”) that all end up as Text nodes in the DOM. However, for historical reasons not all of the spaces and line breaks in the original markup appear in the DOM. In particular, all the whitespace before head start tag ends up being dropped silently, and all the whitespace after the body end tag ends up placed at the end of the body.head element contains a title element, which itself contains a Text node with the text “Sample page”. Similarly, the body element contains an h1 element, a p element, and a comment.script element or using event handler content attributes. For example, here is a form with a script that sets the value of the form’s outputelement to say “Hello World”:<form name="main">

Result: <output name="result">

<script>

document.forms.main.elements.result.value = 'Hello World';

a element in the tree above) can have its “href” attribute changed in several ways:var a = document.links[0]; // obtain the first link in the document

a.href = 'sample.html'; // change the destination URL of the link

a.protocol = 'https'; // change just the scheme part of the URL

a.setAttribute('href', 'http://example.com/'); // change the content attribute directly

Sample styled page

body { background: navy; color: yellow; }

Sample styled page

This page is just a demo.

http://example.com/message.cgi?say=%3Cscript%3Ealert%28%27Oh%20no%21%27%29%3C/script%3E

img, it is important to whitelist any provided attributes as well. If one allowed all attributes then an attacker could, for instance, use the onload attribute to run arbitrary script.javascript:“, but user agents can implement (and indeed, have historically implemented) others.base element to be inserted means any script elements in the page with relative links can be hijacked, and similarly that any form submissions can get redirected to a hostile site.Origin headers on all requests.iframe and then convinces the user to click, for instance by having the user play a reaction game. Once the user is playing the game, the hostile site can quickly position the iframe under the mouse cursor just as the user is about to click, thus tricking the user into clicking the victim site’s interface.img elements and the load event. The event could fire as soon as the element has been parsed, especially if the image has already been cached (which is common).

var img = new Image();

img.src = 'games.png';

img.alt = 'Games';

img.onload = gamesLogoHasLoaded;

// img.addEventListener('load', gamesLogoHasLoaded, false); // would work also

img element and then in a separate script added the event listeners, there’s a chance that theload event would be fired in between, leading it to be missed:

<!-- the 'load' event might fire here while the parser is taking a

break, in which case you will not see it! -->

var img = document.getElementById('games');

img.onload = gamesLogoHasLoaded; // might never fire!

style attribute and the style element. Use of the style attribute is somewhat discouraged in production environments, but it can be useful for rapid prototyping (where its rules can be directly moved into a separate style sheet later) and for providing specific styles in unusual cases where a separate style sheet would be inconvenient. Similarly, thestyle element can be useful in syndication or for page-specific styles, but in general an external style sheet is likely to be more convenient when the styles apply to multiple pages.b, i, hr, s, small, and u.hr element that is an earlier sibling of the correspondingtable element:|

«επιτελεστικές εν-καταστάσεις»

(«performative in-stallations») Επιτελέσεις που καταλήγουν σε έργα τέχνης –εγκαταστάσεις. Εγκαίνια 9 Μαΐου 2013 στις 19.00

Ημερομηνίες για τις επιτελέσεις: 9,10,11|05|2013 στις 19.00 & 20.00 14|05|2013 στις 19.00 Artist talks: Σάββατο 25 Μαΐου, στις 14.00 To Κέντρο Τέχνης & Πολιτισμού Beton7, παρουσιάζει από 9 – 30 Μαΐου 2013 επιτελέσεις που καταλήγουν σε έργα τέχνης – εγκαταστάσεις του Δημοσθένη Αγραφιώτη. Οι επιτελέσεις (performances) έχουν χαρακτήρα συμμετοχικό, δηλαδή, απαιτούν την ενεργό συμβολή των ‘θεατών’. Το τελικό αποτέλεσμα συγκροτεί την έκθεση των παραχθέντων υλικών συνθεμάτων.

Στην όλη διαδικασία συνδράμουν οι: Αντρέας Πασιάς, Θοδωρής Παπαθεοδώρου και Απόστολος Πλαχούρης. Η επιτέλεση (performance) ως ανταλλαγή ενέργειας ανάμεσα στο σώμα του καλλιτέχνη και τα σώματα των συμμετεχόντων μπορεί να καταλήξει στη διαμόρφωση τέχνεργων, αντικειμένων, εικόνων, ήχων. Σύμφωνα μ αυτή την εκδοχή της επιτέλεσης, το παραγόμενο σύνολο θα μπορούσε να διεκδικήσει την υπόσταση του ‘έργου τέχνης’, ‘αισθητικού αντικειμένου’, ή ‘εγκατάστασης’ (installation); Με μιαν άλλη έκφραση, η επιτέλεση θα μπορούσε να έχει διπλό ρόλο: (i) να αποτελέσει αυτόνομη καλλιτεχνική διαδικασία, (ii) να λειτουργήσει ως μηχανισμός παραγωγής καλλιτεχνημάτων; ΕΠΤΑ ΕΠΙΤΕΛΕΣΕΙΣ Ο Δημοσθένης Αγραφιώτης είναι ποιητής, εικαστικός καλλιτέχνης διαμέσων (ζωγραφική, φωτογραφική, διαμέσα/intermedia, performance/επιτέλεση, εγκαταστάσεις). Συγγραφέας βιβλίων με δοκίμια και επιστημονικά άρθρα για την τέχνη, την επιστήμη/τεχνολογία, υγεία ως κοινωνικο-πολιτιστικά φαινόμενα και τη νεοτερικότητα. Ατομικές και συλλογικές εκθέσεις ζωγραφικής, φωτογραφικής και οπτικής/εικονοσχηματικής ποίησης στην Ελλάδα και στο εξωτερικό. Συμμετοχές σε εκδόσεις, κοινωνικο-πολιτιστικές εκδηλώσεις, ταχυδρομική τέχνη, πολυμέσα και διαμέσα, εγκαταστάσεις (ιnstallations) επιτελέσεις (performances), “εναλλακτικές” καλλιτεχνικές δραστηριότητες. Ειδικό ενδιαφέρον για τις συζεύξεις τέχνης και νέων τεχνολογιών – τεχνοεπιστήμης. Έκδοση φυλλαδίου τέχνης ‘Κλίναμεν’ (1980-90) περιοδικού «Κλίναμεν» (Εκδ. Ερατώ, 1990-94) και παραγωγή βιβλίων – καλλιτεχνημάτων (artists books) ‘Κλίναμεν’. ‘Κλίναμεν’ ηλεκτρονικό (2001-). LINKS |

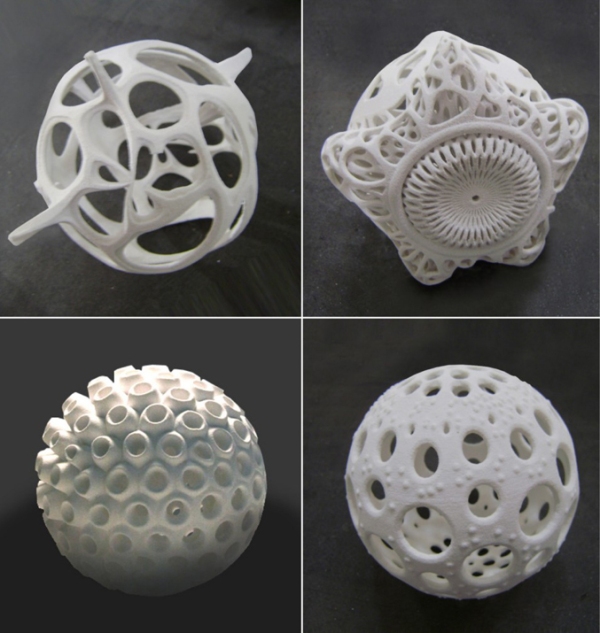

24 Spheres. Time of Change.

0

0

24 Spheres. Time of Change.

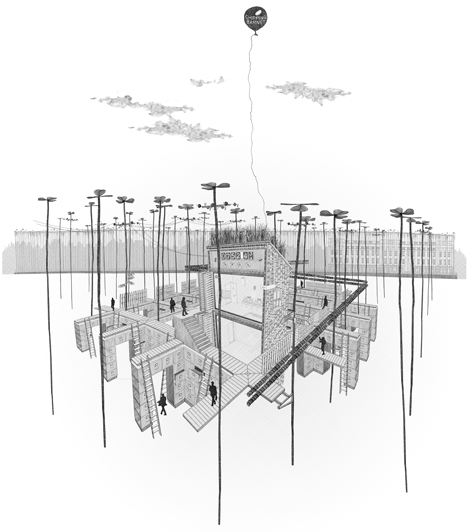

For me Utopia is tied to our ‘now’, to the moment between one second and the next. It constitutes a potential that is actualized and transformed into reality; an opening where concepts such as subject and object, inside and outside, proximity and distance are thrown up in the air only to be defined anew. Our sense of orientation is challenged, and the coordinates of our spaces,collective and personal, have to be renegotiated. Mutability and motion lie at the core of Utopia.” – Olafur Eliasson

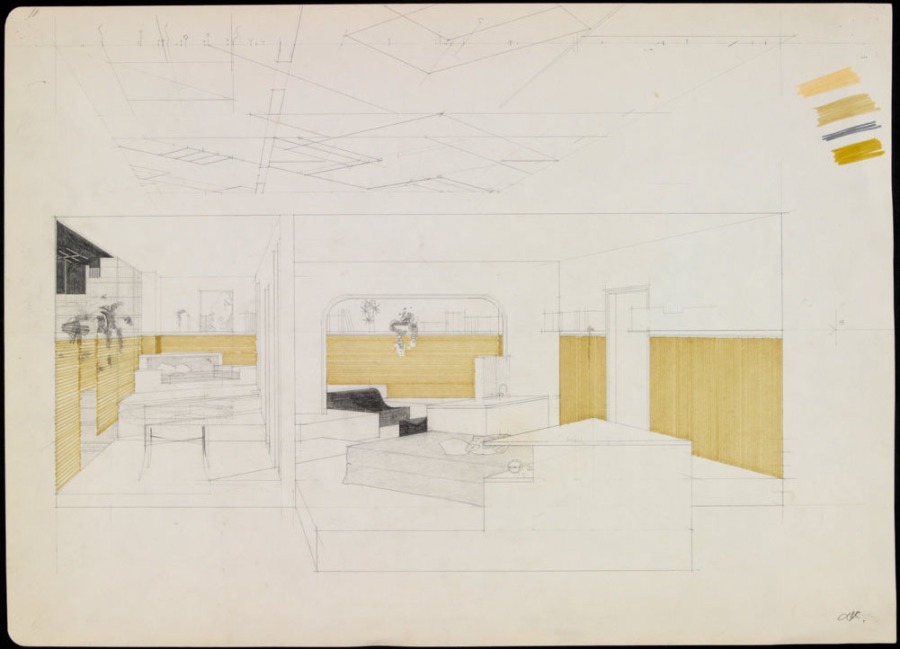

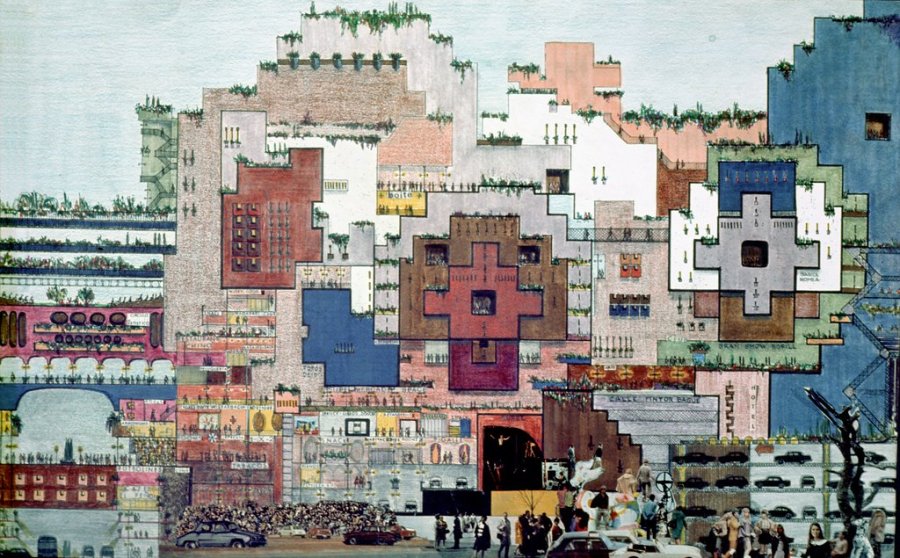

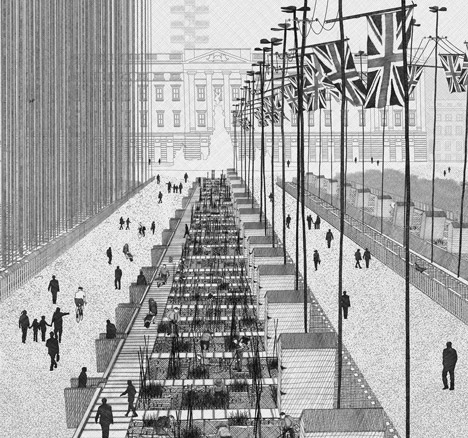

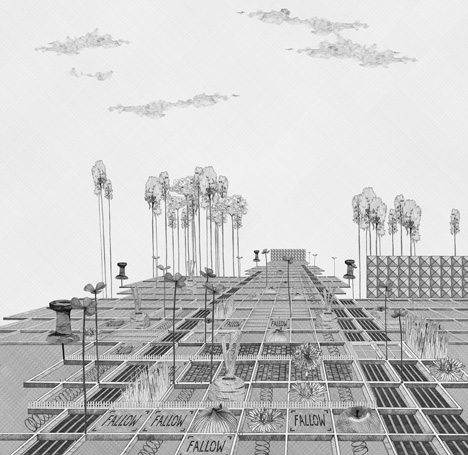

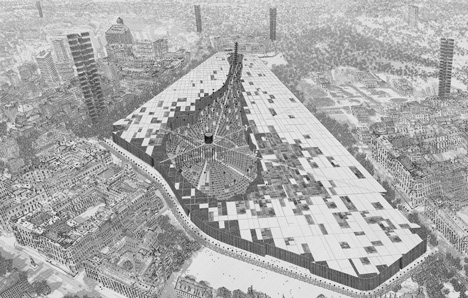

The great majority are ideal projects that never got off the architect’s drawing board. Others are projects that have changed as a result of being altered or demolished, or are ephemeral architecture projects conceived for a brief existence: among these, set designs form a group apart by virtue of their specific logic and clearly differentiated conditioning factors.

This [economical] expansion took place without any type of urban planning nor the slightest degree of democratic control over the economy. Urban chaos and the lack of a basic infrastructure were common in the large cities and the tourist areas on the coast.

I think that we are facing a very interesting era, because architecture always develops in a deeper way in moments of crisis. In the decade of the 60s and 70s, we had the oil crisis, the war, and other conflicts and we had the time to think about ecology, emergency housing, new materials, the space program, etc. And now that we are living in a similar state of the world, we can discover again some similar responses and recover the principles that we have lost.

I’m an ephemeral and not too discontented citizen of a metropolis thought to be modern because all known taste has been avoided in the furnishing and exterior of houses as well as the city plan. Here you cannot point out a trace of a single monument to superstition. Morals and language are reduced to their simplest expression, in short! These millions not needing to know each other pursue their education, work, and old age so identically that the course of their lives must be several times shorter than absurd statistics allow this continent’s people. So, from my window, I see fresh spectres roaming through thick eternal fumes – our woodland shade, our summer night! – New Furies, before my cottage which is my homeland, my whole heart, since all here resembles this – Death without tears, our active daughter and servant, desperate Love and pretty Crime whimpering in the mud of the street.

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE The Shiraz Arts Festival: Western Avant-Garde Arts in 1970s Iran Robert Gluck

iannis xenakis proposal at shah pahlavi;s reign

During the twilight years of Mohammed Reza Shah Pahlavi’s reign in Iran, a panoply of avant-garde forms of expression complemented the rich, 2,500-year history of traditional Persian arts. Renowned musicians, dancers and filmmakers from abroad performed alongside their Persian

peers at the annual international Shiraz Arts Festival. Elaborate plans were developed for a significant arts center that was to include sound studios and work spaces for residencies.

Young Iranian composers and artists were inspired by the festival to expand their horizons to integrate contemporary techniques and aesthetics. Some subsequently traveled abroad for

further study. Although the 1979 Islamic Revolution marked the end of institutions sustaining the avant-garde and scholarships for international study, creative expression sparked by

the festival has continued in cinema and other arts. FOUNDING OF THE SHIRAZ ARTS FESTIVAL

A central goal of Pahlavi rule throughout the 20th century was modernization and industrialization, while still maintaining independence from other nations, particularly Great Britain

and the Soviet Union [1]. Mohammed Reza Shah Pahlavi hoped to ground his independence and authority in three assertions: secular rule, Pahlavi political hegemony and continuity with the ancient, pre-Islamic Persian Empire. In 1967, the Shah crowned himself Emperor and his wife Empress, thereby securing her right of succession. The upcoming 2,500th anniversary (1971) of the conquest of Babylonia by Cyrus the Great, the founder of the Persian empire, provided

a rationale for an international cultural event at the ruins of Persepolis, the ancient pre-Islamic royal seat.

The Shiraz Arts Festival began in 1967 as a showcase for the royal court, especially Empress Farah Diba, a former architectural student, who convened each year’s events. Musician

Gordon Mumma remembers her as “an extraordinary woman

of considerable worldly knowledge” [2]. National Iranian Radio and Television (NIRT), also founded in 1967, served as festival sponsor. Sharazad (Afshar) Ghotbi, a violinist and wife of

NIRT director Reza Ghotbi, was named musical director. Programming reflected Empress Farah’s Western-leaning, contemporary tastes (Fig. 1).

The decision to establish a festival that presented Western-oriented

arts was fraught with potential con- flict. Iran boasted of openness to intellectual ideas and the social integration of women, but the state sharply curtailed internal political

expression, unwittingly fostering the growth of a radical Islamic clerical opposition who would prove to be offended by festival programming. The opulence of the court was on full display throughout the 11 years of events, highlighting the economic distress of the general

populace. Nonetheless, the creative activity featured at the festival reflected the most forward-looking international efforts, presenting Iran to the world as pioneering and open.

EXPERIENCES OF WESTERN=-PERFORMERS AND ATTENDEES

For visiting artists, the Shiraz Arts Festival offered a remarkable experience. Merce Cunningham Dance Company (MCDC) dancers Carolyn Brown and Valda Setterfield recall

their 1972 visit as a “unique . . . wonderful unforgettable adventure” [3] and as “heady and thrilling” [4]. Gordon Mumma

ABSTRACT

Iran in the 1970s was host to an array of electronic music and avant-garde arts. In the

decade prior to the Islamic revolution, the Shiraz Arts Festival provided a showcase

for composers, performers, dancers and theater directors from Iran and abroad, among

them Iannis Xenakis, Peter Brook, John Cage, Gordon

Mumma, David Tudor, Karlheinz Stockhausen and Merce Cunningham. A significant arts

center, which was to include electronic music and recording studios, was planned as an

outgrowth of the festival. While the complex politics of the Shah’s regime and the approaching revolution brought these developments to an end, a younger generation of artists

continued the festival’s legacy.

GLOBAL CROSSINGS

Article Frontispiece.

Valda Setterfield of the Merce Cunningham

Dance Company in a 1968 performance of Rainforest with Andy

Warhol–designed pillows. Rainforest, with the same pillows, was

performed as part of Shiraz Event at the Shiraz Arts Festival in

1972. (Photo courtesy James Klosky)

Fig. 1. Empress Farah greets John Cage and Merce Cunningham

at the 1972 festival. (Photo courtesy of Cunningham Dance

Foundation Archive)calls it “one of the most extraordinary cultural experiences of my life.” Setterfield’s

memories of Shiraz include:

drinking watermelon juice for breakfast,

huge insects buzzing around and drowning in the swimming pool, the heat of the

ground being too much to walk to the

pool without shoes. The nearby market

was wonderful, filled with the sound of

metal pots being beaten into shape and

mysterious things to eat. When the sun

went down, everything smelled like roses.

An elite audience converged on the

festival. Mumma points out that “the cost

of admission was not only money, but also

security clearance.” A 1976 column in

Tehran Journal mixed criticism and gossip: “the Empress [appeared] in a multicolored velvet siren suit that quite

outshone most of the ladies’ gowns” [5].

Brown recalls that the audience “appeared far more interested in looking at

the Queen and her entourage than at the

dancing,” but Mumma found the audience to be serious and interested: “There

were none of the aggressive arguments

about ‘that isn’t music’ stuff that we often

encountered elsewhere.”

Security was tight, as Mumma notes:

“In Persepolis each of us was given a

‘guide’ (read ‘guard’) dressed in a Western suit with a tie and jacket. The primary jacket function was to conceal their

weapons. . . . We traveled in Iranian military aircraft.” Setterfield remembers:

sented Nuits, a choral work dedicated

to political prisoners, some named and

“thousands of forgotten ones whose

names are lost” [8], and in 1969 presented the percussion work Persephassa,

commissioned by the festival and Office

de Radiodiffusion Télévision Française

(ORTF). Persephassa links cross-cultural

legends of the Greek goddess Persephone. Xenakis’s third and final work for

the festival was the commissioned multimedia extravaganza Polytope de Persépolis,

which premiered at the Persepolis ruins

on 26 August 1971. Xenakis describes the

work as

visual symbolism, parallel to and dominated by sound . . . correspond[ing] to a

rock tablet on which hieroglyphic or

cuneiform messages are engraved. . . .

The history of Iran, fragment of the world’s history, is thus elliptically and abstractly represented by means of clashes, explosions, continuities and underground currents of sound [8].

Critic James Harley describes Polytope de Persépolis as“unrelenting in its density

and continuously evolving architecture”

[9].

Xenakis scholar Sharon Kanach reconstructs the scene as follows:

The audience was placed in the ruins of Darius’s Palace and was able to move

freely between the six listening stations placed within these ruins. Each station

had eight speakers, one for each track. . . . The one-hour spectacle began in total

darkness with a “geological prelude” of excerpts from Xenakis’s first electroacoustic work, Diamorphoses (1957). Immediately afterwards, on the mountain facing the site, two gigantic bonfires are lit, projector lights sweep the night sky, and two red laser beams scan the ruins.

Then, several groups of children appear carrying torches and proceed to climb to

the summit, towards the bonfires, outlining in scintillating light the mountain’s

crest. . . . Suddenly, the groups of children disperse and climb down the mountain

in constellation-like figures (Color Plate E) and finally congregate between the

two tombs where their torches spell out in Persian “we bear the light of the

earth,” a phrase by Xenakis. One last outburst and the 150 torch-bearers run past

the ravine and disappear through the crowd into the forest [10].

The new work faced mixed reactions. The Empress and NIRT liked it enough

to offer Xenakis a further commission for the design of a proposed art center. However, some Iranian critics, sensitive to the legacy of Western hegemony in Iran, associated Greek composer Xenakis’s torch spectacle with the burning of Persepolis

by Alexander the Great [11] or suggested that the symbolism could be interpreted

as the actions of Nazi brownshirts [12].

“Persepolis was absolutely filled with soldiers with rifles. They seemed to appear

out of the woodwork at every corner.

There was a real sense of wariness and

danger. You looked at something extraordinary, old and beautiful, and suddenly you would see the soldiers.” Merce

Cunningham discovered that pillows

used in the Persepolis performance

“were in a room full of machine guns”

[6].

PROGRAMMING

The Shiraz Arts Festival always include traditional music from around the world.

The 1967–1970 programming included

Indian sitarist Ustad Vilayat Khan, American violinist Yehudi Menuhin, numerous Persian classical musicians and artists, a Balinese gamelan ensemble, the Senegalese National Ballet and performances of the Persian passion play ta’ziyeh

(“mourning” or “consolation”) portraying the founding of Shi’a Islam [7].

Ta’ziyeh, banned under the Shah’s father,

influenced avant-garde Western theatrical directors Peter Brook, Jerzy Grotowski

and Joseph Chaikin (who brought The

Open Theatre [Fig. 2]). Visiting dance

companies included Merce Cunningham

in 1972 and Maurice Bejart in 1976.

The Western composer most closely

associated with the Shiraz Arts Festival

was Iannis Xenakis, who in 1968 pre-

22 Gluck, The Shiraz Arts Festival

GLOBAL CROSSINGS

Fig. 2. Performance of Joseph Chaikin’s Open Theater at the 1971

Shiraz Arts Festival. Still image taken from a Pars Video documentary.Xenakis (Fig. 3) responded that “fire

and light represented goodness and

eternal life . . . using children today as

torch-bearers, representing the men and

women of tomorrow, is a cry of hope for

the future” [13].

The 1972 festival was a veritable Stockhausen festival, the composer’s “highlight of the year” [14], featuring three

“intuitive” compositions and Gruppen,

Carre, Stimmung, Gesang der Jünglinge, Telemusik, Prozession, Kontakte, Spiral, several

Klavierstücke, Hymnen (Fig. 4) and Mikrophonie I. MCDC dancer Brown describes

Stockhausen’s appearance at the festival as like that of a “guru . . . walking the

streets of Shiraz white robed.” The festival closed with an outdoors performance

of Sternklang, in which

a seething mass of about eight thousand

poured up the star-shaped converging

paths. . .the spectators squashed together

on the pathways, besieging the performers . . . [some] clambered up the loudspeaker scaffolding and were hauled

down again by the police . . . Stockhausen

was convinced that his music would calm

the listeners. And so it was. After half an

hour of music the waves subsided [15].

Tehran Journal described the 1972 festival as “the most avant-garde and most

controversial Shiraz Festival so far” [16].

Electronic music dominated the offerings, which included numerous concerts

by Stockhausen, performances by MCDC

featuring musicians John Cage, David Tudor and Gordon Mumma, and tradiwas helium-filled pillows designed by

Andy Warhol (Article Frontispiece), tethered to the ancient pillars, as Mumma recalls, to “keep them from floating away

from the performance.” Company administrator Jean Rigg remembers that

“The winds came up, and many simply

snapped their lines and floated off . . . the

effect was great” [21].

The musical concert included

Mumma’s Ambivex (“a composition for

trumpet [or cornet] with live cybersonic

modification”) and a simultaneous performance of Cage’s Birdcage and Tudor’s

Monobird (Fig. 6) [22]. Birdcage (1972)

is a “complex, exuberant, and joyful” collage composed from sounds of birds,

“Cage singing his ‘Mureau’ and . . . ambient sounds” [23].

IMPACT ON YOUNG

COMPOSERS AND ARTISTS

The festivals proved influential on the rising generation of Iranian artists and composers. Brown recalls: “John Cage was

greeted by many devoted fans as a muchloved ‘hero.’” Students at Tehran University, such as Persian-American composer

Dariush Dolat-shahi, experienced the festival close up because the music department was actively involved in the events.

Dolat-shahi recalls that “Every year, I

waited for the event to happen. These festivals were a major source of information

for us about what was happening musically outside Iran. I received my own first

commission when I was nineteen years

old” [24].

Dolat-shahi became “part of a group

of four people who used to get together

and listen to modern music including

Schoenberg, Berg, Ligeti,” and realized

his first work for strings and tape, popular instrumentation during the festivals, using a small tape recorder. Festival

performances also influenced the development of Iranian theater, as IranianAmerican writer and theater artist Zara

Houshmand observes about a recent

Tehran performance directed by Majid

Jafari: “Jafari’s work, like that of Pessyani

and so many Iranian directors, owes

a huge debt to Jerzy Grotowski, Peter

Brook, Tadeusz Kantor, and other leading lights of the European avant-garde

who accepted invitations to the Shiraz

Festival before the revolution” [25].

Government agencies offered scholarships to support young artists to study

abroad. Among them were Dolat-shahi,

supported by NIRT, and Massoud Pourfarrokh, supported by the Iranian Ministry of Art and Culture. The Shah once

wrote:

tional Persian and South Indian music

and contemporary Iranian theater and

film. Electrical power needed to be

brought into Persepolis from outside,

notes Mumma, “by truck and horsedrawn wagons. I was told that much of

that sound equipment was obtained on

loan from the Deutsche Rundfunk by the

Iran government.”

Merce Cunningham Dance Company

gave outdoor dance performances at Shiraz and Persepolis, plus a musical concert. The dance performances included

two “Events,” composed of material selected from the company’s repertoire

“to allow for, not so much an evening

of dances, as the experience of dance”

[17]. The choreography was unrelated to

the music, which included John Cage’s

one-minute stories making up Indeterminacy [18] and circa-1930s Argentine

tangos. An “official” festival reviewer

wrote: “Tuesday night, alas, was unintense, overlong, extended, and—except for such ecstatic moments—tedious

and exhausting” [19]. Music for Persepolis Event (Fig. 5) included Signals and

Landrover, collaborative compositions by

Cage, Tudor and Mumma, and Tudor’s

Rainforest (1968), which Mumma recalls

was “performed with a forest of electroacoustic transducers of his own uncanny

design” [20].

Setterfield remembers dancing at the

ruins of Persepolis as “glorious and physically hard . . . the ground was rocky, so

we had to wear shoes.” The only décor

Gluck, The Shiraz Arts Festival 23

GLOBAL CROSSINGS

Fig. 3. Iannis Xenakis

in a heated dialog

during the 1971 Shiraz

Arts Festival. Screenshot from a Pars Video

documentary.It requires lively insight and imagination to transplant Western technology effectively to a country like Persia. As I

have said, much adaptation is necessary,

and we largely rely for this upon the

young men whom we send abroad for

post-graduate study and who naturally

encounter the problem of using their

new knowledge in home conditions.

Many of these adaptations are almost instinctive or unconscious, but others may

require extended research [26].

AsGordon Mumma observes, “the outward looking ideas of the Iranian government and the aspirations of their

intellectuals and younger creative artists”

pointed to such collaboration.

Dolat-shahi first studied abroad in Amsterdam in 1970. In 1974, he returned to

Tehran, but “felt the need to continue my

education” and thus received an additional scholarship to attend Columbia

University, where he was already familiar with the works of faculty members Milton Babbitt and Vladimir Ussachevsky.

NIRT expressed interest in training him

to play a staff role in the proposed new

arts center being developed by Iannis Xenakis and sponsored by NIRT. “The idea

for this studio had a lot of support, since

a lot of electronic music was performed

at the festivals. They wanted to have a major center of their own” [27].

compose music, including electronic music for a time, in Iran. Dolat–shahi recalls

that in 1977 NIRT commissioned a work

for electronics and chamber orchestra

for the 1977 festival from ColumbiaPrinceton director Ussachevsky, but a few

months before Ussachevky’s scheduled

departure from the United States, the declining political situation made a visit impossible. Chou Wen-Chung, chairman of

the Columbia University music department, also visited Iran. He recalls:

My students Massoud Pourfarrokh and

Dariush Dolat-shahi told about many of

the problems faced by Iranian students.

They came up with the idea of setting

up a cultural exchange between the two

countries at Columbia University, like

The Center for U.S.-China Arts Exchange

that I had already established. . . . Massoud and Dariush arranged for me to go

to Iran and meet with officials in that

country.

The three of us went together as private citizens. It was probably in the late

spring or late August of 1978, before the

school year began, and we made a connection with the Minister of Culture. He

was a very powerful man, quite westernized and close to the Shah. The Ministry

building was like a palace. We had a couple of very productive sessions together.

He was very pleasant and knowledgeable,

well briefed on the intention of my trip.

The Minister was very supportive of this

Dolat-shahi thus began work at the

Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music

Center in 1976, preparing the tape portion of his festival-commissioned piece

From Behind the Glass, a composition for

20 strings, piano, tape and echo system.

Critic Janet Lazarian Shaghaghi wrote

that the work “conveyed a stimulating

imagination of space, was original and

good to listen to” [28]. The official festival program observed that “electronic

music liberated [Dolat-shahi] from old

concepts of melody and harmony and

provoked further explorations into the

raw material of music, i.e. sound” [29].

The 1976 festival also included Dolatshahi’s Two Movements for String Orchestra

(1970) and Miragefor orchestra and tape,

which, wrote Shaghaghi, “easily unfolded

its beauty; it bloomed as fast as it was

started, the sound effects and the orchestral music blended harmoniously”

[30]. The programming also included

music by other forward-looking Iranian

composers such as Alireza Mashayeki,

Mohammad Taghi Massoudieh and Hormoz Farhat, then head of the television

network’s Music Council and an artistic

advisor of the festival.

The final festival in 1977 featured

works by Fawzieh Majd, Ivo Malec, Bach

and Mashayeki, who continues to actively

24 Gluck, The Shiraz Arts Festival

GLOBAL CROSSINGS

Fig. 4. The 1972 performance of Hymnen at Persepolis, from the archives of the Stockhausen Foundation for Music,

Kuerten .new idea and he offered to provide substantial funding.

The Center would have been something quite exciting. It was to be broadly

based around music in the context of a

cultural exchange between the two countries. Iranian scholars and composers

would come to the United States to interact with their American counterparts

and be exposed to more advanced studies in terms of compositional principles

and technology. There was interest on

both sides for it to include electronic music. My interest on behalf of Columbia

University was to send American musicians and scholars to research Persian

music in Iran, not just ethnomusicology,

but also looking to the future of their music. The Minister of Culture was interested in developing a center for cultural

exchange in which students from both

countries could study the old, represented by Iran, and the new, represented

by the United States.

The rest was up to me to convince Columbia University to work with us. There

was no question in my mind that it would

indeed happen. The next step would

of everything, but to hire Iranians locally

to execute his ideas” [34].

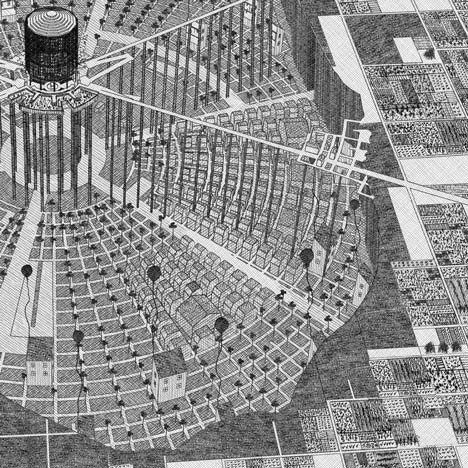

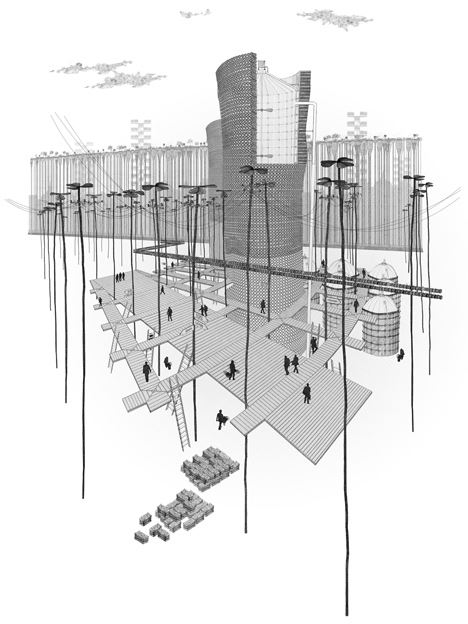

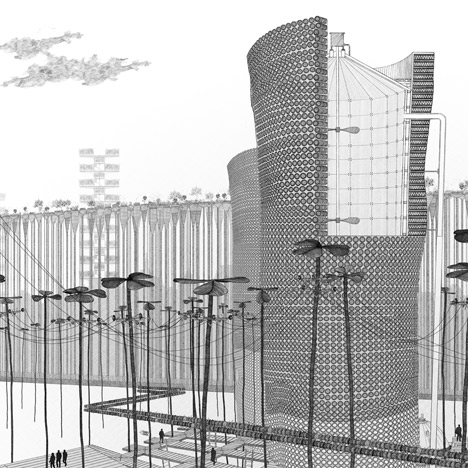

To summarize Xenakis’s proposal, according to his “General Guidelines,” the

Center was to be an interdisciplinary and collaborative “scientific research center”

for sound and visual arts, cinema, theater, ballet, poetry and literature, to “continue

all the activities year round of the Annual Festival of Shiraz-Persepolis.” In addition

to public presentations, the center would support ongoing work by up to 40 visiting and 50 permanent artists, scientists and staff members. It was to be “essentially based on the most advanced research and technological events, leading us towards the future of Art,” open to all

people, fostering exchange between its participants and the city (not “an intellectual ghetto”), sharing resources with the university, cultivating traditional arts

“observed through the light of the most advanced research and experimentation

have been to invite the Minister of Culture to the United States, agree on terms

and get the Center started [31].

These plans collapsed, as did planning

for the 1978 festival, as the revolution approached.

A PROPOSED CENTER

FOR THE ARTS

The success of Xenakis’s monumental Polytope de Persépolisled to his engagement

as “Engineering consultant in charge of the architecture of a Cité des Arts in

Shiraz-Persepolis” [32]. Discussions for the proposed center actually may have

begun as early as 1968 [33]. Xenakis’s design was based upon his plan for “a very

similar project he devised [in 1970] as a Le Corbusier Center for the Arts [in

Chaux-de-Fonds]. The plan, as far as can be told, was to make Xenakis in charge

Gluck, The Shiraz Arts Festival 25

GLOBAL CROSSINGS

Fig. 5. Persepolis Event, Douglas Dunn (left), Carolyn Brown (rear) and Merce Cunningham (far right).

(Photo courtesy Cunningham Dance Foundation archive)and not through the normal musicological, theatrical, choreographic . . . academic traditions.”

In his plans, Xenakis referred to the

sound arts element as a “Center for Studies of Mathematical and Automated Music,” which Kanach believes likely to

have been similar to Xenakis’s center in

Paris, CEMAMu, the Center for Studies

in Mathematics and Automation of Music. The proposed center was to include

laboratories for “automated” digital and

analog music and film sound editing,

two recording studios, a library and repair workshop, a 10,760-square-foot “Hall

of Nothingness” and parking facilities

for 1,000 cars. The proposed budget was

35,000,000 francs (approximately US$7

million) [35]. As nothing was put into

writing at the time, it is possible that

plans never reached the stage at which

administrative details, including Dolatshahi’s formal role, would be defined.

POLITICAL

CONSIDERATIONS

AND CONFLICTS

The politics involved in Western artistsparticipating in the festival and proposed

arts center were complex. Negative reactions by Iranians to Xenakis’s Polytope de

Persépolis extended to Iranians living in Paris, the composer’s home city. There,

Islamic opponents of the Shah publicly criticized Xenakis for collaborating with

who, like yourself, have made the ShirazPersepolis Festival unique in the world.

But, faced with inhuman and unnecessary police repression that the Shah and

his government are inflicting on Iran’s youth, I am incapable of lending any

moral guarantee, regardless of how fragile that may be, since it is a matter of artist

creation. Therefore, I refuse to participate in the festival [37].

Other artists also experienced conflicts with the political situation in Iran. Carolyn Brown recalls that while there was no controversy about MCDC’s 1972 visit,

“we were not unaware of the political difficulties and sensed there was worse to

follow.”

Merce Cunningham Dance Company was invited to return a few years later…………………………………………………………………………………………….

music in relation to perception of time

questions

time

http://0708013circle02a.blogspot.gr/2008/06/time-project.html

site – pic-nic 7+

The RKO method was to do a perfect carpentry job with dressed lumber from the studio stockpile and then chop up the result with axes and chisels in order to denote rude construction […] It was my painful duty to interrupt this process and have the stairway built of logs, saplings, charred timber, old doors, and other material that any reasonable person would consider more available under the conditions of the story.[7]

The same picture called for a peasant cart made of crude lumber. I found just the right material for it on a nearby ranch – rough boards that had lain for years in the open. The cart was built at the ranch and was brought to the studio. Next day I saw it in one of the studio alleys. It had been painted a fine, spanking battleship gray all over; all texture was gone, and you couldn’t tell the wood from the metal parts. It became necessary to repaint the cart with artificial wood graining in an effort to restore some of its original appearance.[11]

Naturalism has a revolutionary aspect, for it shows the social conditions which the bourgeois theatre takes great pains to conceal. Also, a call to fight is sounded, which proves that the fighters exist. But only in a second phase does proletarian theatre begin, politically and artistically, to qualify itself for it social function. The first phase shows that the class struggle does exist. The second shows how it ought to be conducted.[16]

No Epic play or film can hope to present facts which will not be questioned, no matter how well supported the evidence may be. What is significant is the tendency to rely upon facts, to rely upon the objective logic of events rather than upon subjective emotion.[23]

For the back alley of the Fun Fair in Lonely Heart the art factory offered a piece of prosaic naturalism, without regard to the fact that this alley was one of the most romantic locales in the story. Again I was obliged to redesign, curving the walls of the alley, arching it with trees, placing shadowy hoods over doors and windows. This shift towards a more poetic imagery was meaningless to the art regime.[25]

It is made of lath, covered with black velours. Its fire is a red spotlight. Its steam is real steam blown by a fan. Its bell is a sound taken on the New York Central Line. Its sway is produced by two stagehands operating levers on either end. Its cost was 81,500.[27]

There was a task, however, for which a similar venture into form and structure would prove beneficial. In 1918, the film director Paul Wegener commissioned Poelzig to design the sets for a third film version of Der Golem (The Golem). Poelzig readily accepted the job – their “shared interests in the mysterious and fantastic” undoubtedly “made the collaboration on The Golem easy and fruitful.” As for the 1920 film, it was Wegener’s third version of the Austrian writer Gustav Meyrink’s 1915 novel of the same name. The novel and the film share very little in terms of story line, with Wegner creating an unusual blend of Jewish mysticism and expressionistic élan. Yet the film has a distinct urban flavor – set in the 16th century it tells the tale of the scrupulous and shrewd Rabbi Löw, the most outspoken of Prague’s Jewish community. In response to a premonition that a terrible disaster would befall Prague’s Jewish population (shortly afterwards, local secular authorities would issue an edict to expel and relocate the city’s Jewish population), Rabbi Löw consults his own circle and they decide to build a Golem, an anthropomorphic clay-hewn monster that will protect the people. However, the monster loses control and begins destroying Prague.

Along with this wife, the sculptor Marlene Moeschke, Poelzig designed a whole city for Wegener’s production of The Golem. The director did not want Poelzig to design a typical Medieval village.

We also forget that the utilization of structures from earlier times for a building designed to meet the demands of modern life must be accompanies by an unmistakably modern adaptation of these structures, and that the correct use of materials and construction consciously adapted to purpose produce inner advantages that cannot be replaced by decorative embellishments, however skillfully applied.

However, some critics did not agree that Poelzig put his principles to practice. In 1920,

… for here everything from the first to the last is sham. This colossal, solid looking … building is a glittering stage set, a complicated, artistic, architectural mask of plasterboard. All the elements that seem to be growing, to carry, to support and vault are actually being carried, supported, vaulted. The entire mass of the building is suspended on the old iron frame. The whole thing is a web of wire with plaster thrown on it. The plaster has been modeled and then painted with bold colors. Here even the architecture is playacting. This kind of architecture, thrown up like this, has nothing to do with craftsmanship in the good old-fashioned sense of the word.

*

john cage

the first impression

chaotic-noisy disorganized

Cage originally made his chance decisions by tossing yellow sticks or coins , according to practices described in the I think.

he later found found a more productive way

-categories of sounds (urban, wind,……-produced, manually produced sounds(including musical instruments) -what today looks as an easy assignment -recording literally hundred of sounds (barrons) -elements -sound recordings (equipment)

http://www.youtube-nocookie.com/embed/LAVQPUUiBN0?list=PL3A7AD14495922045

get sound forge-vegas// get open source audio programms

j

R650 All our o the synesthete subjects(S1–S4, ages 23–33, 1 woman) hadnormal visual acuity and no knownhearing or neurological decits. Theirvisually-induced sound perceptionsoccur automatically, cannot be turnedo, and have been experienced oras long as they can remember goingback into childhood. The percepts aretypically simple, non-linguistic sounds(such as beeping, tapping or whirring)that are temporally associated withvisual fashes or continuous visualmotion. Eye movements over astationary scene (retinal motion) donot typically evoke sound. In dailyexperience, all our subjects aregenerally able to distinguish theirsynesthetic sound percepts rompercepts induced by real auditorystimuli, but occasional conusionexists. We reer to this phenomenonas ‘hearing-motion’ synesthesia, eventhough non-moving visual fashesalso trigger sound perception asdemonstrated next.Our goal was to devise a task orwhich hearing-motion synesthesiawould coner a perormance advantage, as this would bestrong objective evidence or theperceptual experience[4]. Typically(in non-synesthetes), people have anadvantage in judging rhythmic patternso sound compared to equivalentvisual rhythmic patterns[7,8]. We thuspredicted that synesthetes wouldperorm better  than controls in a taskinvolving visual rhythmic sequencesbecause synesthetes would not onlysee, but also hear the patterns.

than controls in a taskinvolving visual rhythmic sequencesbecause synesthetes would not onlysee, but also hear the patterns.

The sound ochange: visually-induced auditorysynesthesiaMelissa Saenz and Christo KochSynesthesia is a benign neurological condition in humans characterized by involuntary cross-activation othe senses, and estimated to aectat least 1% o the population[1].Multiple orms o synesthesia exist,including distinct visual, tactile orgustatory perceptions which areautomatically triggered by a stimuluswith dierent sensory properties[1–6],such as seeing colors when hearingmusic. Surprisingly, there has beenno previous report o synestheticsound perception. Here we report thatauditory synesthesia does indeed existwith evidence rom our healthy adultsor whom seeing visual fashes orvisual motion automatically causes theperception o sound. As an objectivetest, we show that ‘hearing-motionsynesthetes’ outperormed normalcontrol subjects on an otherwisedicult visual task involving rhythmictemporal patterns similar to Morsecode. Synesthetes had an advantagebecause they not could not only see,but also hear the rhythmic visualpatterns. Hearing-motion synesthesiacould be a useul tool or studying howthe auditory and visual processingsystems interact in the brain.ASample ‘same’trial:interval 1:interval 2:Sample ‘different’trial:Sample rhythmic sequence composed of flashes or beeps:20050100Time (ms)interval 1:interval 2:p< 0.0001N.S.Controls(n=10)Synesthetes(n=4)B1009080706050 % c o r r e c tSoundVisionCurrent BiologyFigure 1. Visually-induced auditory synesthesia.(A) Sequences were composed o intermixed long (200 ms) and short (50 ms) duration stimuliseparated by blank intervals (100 ms) similar to Morse code (bars depict stimulus on-times). Thestimuli were either tonal beeps (360 Hz) on sound trials or centrally fashed discs (1.5 deg radius)on visual trials. On each trial, subjects judged whether two successivesequences (either bothsound or both visual) were the ‘same’ or ‘dierent’. (B) Mean perormance (% correct trials) orcontrol and synesthete subjects (+/− SEM). All subjects had good accuracy on sound trials, butsynesthetes dramatically outperormed controls on the otherwise dicult visual trials. Movies osample trials located online at http://www.klab.caltech.edu/~saenz/hearing-motion.html.thereore emerges whereby one othe key unctions o the intact basalganglia is to link positive outcomesto subsequent behaviour, whetherpredominantly cognitive or motorin its demands, and to modiy thisrelationship accordingto motivational state.Supplemental dataSupplemental data are available athttp://www.current-biology.com/cgi/content/ ull/18/15/R648/DC1 AcknowledgmentsThis work was supported by the MedicalResearch Council, Welcome Trust, FWO- Vlaanderen and Strategisch Basisonderzoek.Reerences1. Niv, Y. (2007). Cost, benet, tonic, phasic: whatdo response rates tell us about dopamine andmotivation? Ann. NY Acad. Sci.1104, 357–376.2. Satoh, T., Nakai, S., Sato, T., and Kimura, M.(2003). Correlated coding o motivation andoutcome o decision by dopamine neurons.J. Neurosci. 23, 9913–9923.3. Brown, P., Chen, C.C., Wang, S., Kühn, A.A.,Doyle, L., Yarrow, K., Nuttin, B., Stein, J.,and Aziz, T. (2006). Involvement o humanbasal ganglia in o-line eed-back control ovoluntary movement. Curr. Biol.16, 2129–2134.4. Hamani, C., Saint-Cyr, J.A., Fraser, J., Kaplitt,M., and Lozano, A.M. (2004). The subthalamicnucleus in the context o movement disorders.Brain127, 4–20.5. Frank, M.J., Seeberger, L., and O’Reilly, R. C.(2004). By carrot or by stick: Cognitivereinorcement learning in Parkinsonism.Science 306, 1940–1943.6. Shohamy, D., Myers, C.E., Onlaor, S. Grossman,S., Sage, J., Gluck, M.A., and Poldrack,R.A. (2004). Cortico-striatal contributions toeedback-based learning: Converging datarom neuroimaging and neuropsychology.Brain127, 851–859.7. Kemp, F., Brücke, C., Kühn, A.A., Schneider,G.H., Kupsch, A., Chen, C.C., Androulidakis, A.G., Wang, S., Vandenberghe, W., Nuttin, B.,et al.(2007). Modulation by dopamine o humanbasal ganglia involvement in eedback controlo movement. Curr. Biol.17, R587–R589.8. O’Doherty, J., Dayan, P., Schultz, J.,Deichmann, R., Friston, K., and Dolan, R.J.(2004). Dissociable roles o ventral and dorsalstriatum in instrumental conditioning. Science 304, 452–454.9. Wrase, J., Kahnt, T., Schlagenhau, F., Beck, A.,Cohen, M.X., Knutson, B., and Heinz, A. (2007).Dierent neural systems adjust motor behaviorin response to reward and punishment.Neuroimage 36, 1253–1262.10. Tricomi, E.M., Delgado, M.R., and Fiez, J.A.(2004). Modulation o caudate activity by actioncontingency. Neuron41, 281–292.1Department o Neurology and2Departmento Neurosurgery, Charité-University MedicineBerlin, CVK, Berlin, Germany.3SobellDepartment o Motor Neuroscience andMovement Disorders, Institute o Neurology,London, UK.4Department o Neurosurgery,Kings College Hospital, Denmark Hill, London,UK.5Department o Physiology, Anatomy andGenetics and6Department o NeurologicalSurgery, Radclie Inrmary, Oxord, UK.7Department o Neurology and8Neurosurgery,Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Belgium.E-mail:p.brown@ion.ucl.ac.uk

Powered by WordPress