23 Φεβρουαρίου 2013

Schnabel Julian

basquiat documentary

22 Φεβρουαρίου 2013

LUIS

… Film d’avant-garde de Luis Buñuel, avec Gaston Modot (l’homme), Lya Lys (la femme), Germaine Noizet, Lionel Salem, Max Ernst (le chef des bandits).

Scénario : Luis Buñuel, Salvador Dalí

Photographie : Albert Duverger

Musique : Georges Van Parys (arrangements d’après Wagner, Mendelssohn, Mozart, Beethoven, Debussy et des paso-doble)

Pays : France

Date de sortie : 1930

Durée : 1 h 01

———————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Román Gubern and Paul Hammond’s excellent new biography of the surrealist filmmaker Luis Buñuel reveals the reactionary impulses behind his anarchical facade.

James Heartfield

Filmmaker Luis Buñuel made a name for himself, along with the painter Salvador Dali, overthrowing the rules of filmmaking with surrealist masterpieces like Un Chien Andalou and L’Age d’Or (meaning ‘Age of Gold’, it also sounds like ‘Large Door’ in English). These were followed by avant-garde films like That Obscure Object of Desire and The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie. But until now, Buñuel’s work in Spain, and for the Republic in the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), has been largely unknown. Román Gubern and Paul Hammond’s brilliant and exhaustive new book, Luis Buñuel: The Red Years, 1929 – 1939, fills in the gap.

Surrealism was dismissed in Britain for many years. Un Chien Andalou was very rarely screened: the surest way to ‘see’ it was by listening to the singer and critic, George Melly, retell every one of its series of nightmarish scenes. The surrealists overturned the symbolic meaning of things, bringing together jarring images in their wilful disruption of aesthetic beauty and meaning. Nowadays it is commonly understood that this was the most interesting movement in modern art and it’s a shame that the surrealists’ ideas were diluted down to homoeopathically small doses in Pop Art and, later, in the works of the Young British Artists. As a result, surrealism has lost its shock value. In their day, and to their delight, the surrealists’ work caused outrage, just as dadaist Marcel Duchamp’s ‘Fountain’ (a urinal signed ‘R Mutt’) had a few years earlier. By contrast, today, visitors to Tate Modern in London, where the urinal is on permanent display, walk reverentially around it, as if it were a holy relic.

The surrealists set out to wage war on bourgeois respectability. The movement was bound up with the growing social revolution that challenged the capitalist order in the early twentieth century. According to Buñuel’s collaborator Jean-Claude Carrière, ‘the real desire was not aesthetical, but social; revolutionary. It was a revolutionary movement. They were young and they really wanted to change the world, using scandal, provocation, poetry, dark explorations of the mind as weapons.’

‘Of course it was a chimera’, Carrière goes on to say, ‘but that was the point’. Gubern’s and Hammond’s book shows that the surrealists’ goal of revolutionising society brought them into alliance – and then conflict – with the Communists who put themselves at the head of the revolution.

Both Buñuel and Dali were latecomers to surrealism. As students in Madrid they, along with poet and playwright Federico Garcia Lorca, were thrilled by stories of the outrageous anti-art movement led by Luis Aragon and André Breton in Paris. Buñuel wangled a job with the League of Nations’ cultural department in Paris and stalked the surrealists at their favourite cafés. He made little impact, though. His friends were already noted talents in painting and poetry so Buñuel sought out jobs in the new cinema industry.

Between them, Buñuel and Dali worked up the extraordinary scenario of Un Chien Andalou – with its remarkable opening sequence of a girl’s eye cut open with a razor (they cut from the actress to a dead calf, shaved and made up, Gubern and Hammond tell us, to get the effect). Each vetoed any image that the other came up with if it seemed predictable. Their aim was to impress the cliquish surrealists – and it worked. The surrealists had already made quite an impact and the film’s reception boosted their reputation still further.

The revolutionary wave that swept the world at the close of the First World War, going furthest in autocratic Russia where the Tsar was overthrown and the first Workers’ and Peasants’ Government was founded, added to the feeling that the old order was falling apart. All over the world, radical agitators and working-class militants gathered in Communist parties inspired by the new Soviet Union to overthrow capitalism. Their declaration of intent, though, isolated them. As the European revolution ebbed, the Communists became more defensive and more conservative. Hoping above all to save the Utopia in Russia (and unwilling to accept that it had descended into a dictatorship), the Communists mobilised workers to lobby for a better life and increasingly struck a conservative note, decrying capitalist ‘decadence’ and immorality. The great cultural experiments of the Soviet Union in the 1920s gave way to deadening formulae, first of a stodgy ProletCult, and then of a cod-classical Socialist Realism. For the surrealists reaching out to this wider movement, the Communists’ cultural conservatism was confusing.

The surrealists were called into the Communist headquarters in Paris to be told ‘by a comrade from Agit-Prop’ that ‘Surrealism was a movement of bourgeois degeneration’ (similar accusations were made by George Orwell against Dali and by Georg Lukacs against Ernst Bloch). Breton took the point, writing: ‘I don’t want to provide any fodder for aristocrats and bourgeois, I intend to write for the masses … even if it means abandoning surrealism.’ Here, the best and most prophetic lines are Dali’s in a letter to Buñuel (although the impact is undermined somewhat by Dali’s later sucking up to the Fascist Franco) : ‘[T]he mere fact of becoming a member of the Communist Party nullifies all trace of intelligence in individuals like Aragon and you… Today, everything is violently censured by the Stalinists, who are preparing the most chaste, backward society history has ever known: playing draughts, physical culture and so-called wholesome natural love(!).’

Down with the reactionary, bourgeois optimism of the Five Year Plan! Long live Surrealism!

Dali got the key point about the dramatic, but instrumental, films coming out of the USSR: ‘It isn’t a question of artistic errors… The films, the proletarian literature shit, etc, etc. These are films and works with a message, with an aim that’s exclusively to do with propaganda.’ Buñuel understood the criticism, but he did not share the political judgement. As Gubern and Hammond have painstakingly uncovered, Buñuel was not just a fellow traveller but an enthusiastic member of the Communist Party, in spite of the strictures against ‘decadent art’.

The decade that Gubern and Hammond have lit up for us is one in which Buñuel worked hard for Estudia-Proa Filmofóno, the distribution and later production company. The company, which was probably set up with the help of the Comintern agent Willi Munzenberg, distributed Soviet films – and Disney shorts – in Spain. For its director, Ricardo Urgoiti, Buñuel dubbed foreign films and made many melodramas, often from the popular plays of Carlos Arniches. They included the weepie Juan Simon’s Daughter. These films were workmanlike, but hardly the arthouse cinema that Buñuel’s early shorts promised – and they were not credited to him, either. One early collaborator explains that Buñuel ‘agreed to work in Filmofóno out of friendship for Ricardo Urgoiti but didn’t want to sign the films, since it would have put an end to his fame as an enrage avant-gardist’.

These works, on closer examination, have lots of the unsettling juxtapositions and sadistic and predatory themes that mark Buñuel’s better-known work, though they are for the most part unremarkable. ‘I produced various Arniches films to amuse myself and to earn money’, Buñuel explained. He also used his time to become a master of the economy of time, planning out his filming in meticulous detail so that he used less film stock, fewer days and less money than other directors.

One project that Buñuel did put his name to was Land without Bread, a striking protest against the poverty of the mountainous northern region of Spain. The film fits many of the canons of social realist cinema, though Gubern and Hammond argue that there are many touches that are so melodramatic that they are more surreal than realist. The film’s social protest message is in keeping with the Spanish Communist Party’s marked hostility to the Spanish Republic before 1936, when its favoured slogans were ‘Down with the Bourgeois Republic!’ and ‘For a Workers’ and Peasants’ Government!’. The Communists praised Buñuel for Land without Bread, and for leaving behind the ‘complicated intellectualism’ of his earlier work. The Republic banned it, saying it was bad for Spain’s image.

In 1936, everything changed. The Socialist and Communist left won the elections and were even granted some ministerial posts in the government. The military launched its Fascist revolt against the Republic, which was quickly put down in Spain, before regrouping in Morocco to open its three-year fight to destroy democracy. The Communist Party became the chief defender of the ‘Bourgeois Republic’, which meant that Land without Bread remained banned. In the first days of the defeat of the Fascists, working-class Spaniards let rip their hatred of the landlords and the church, seizing land and smashing up churches while often disinterring the buried priests and saints. Spain had many anarchists and a tradition of Jacqueries that went back, not just to the Tragic Week at the end of the 1909 Rif War, but right back into the nineteenth century. As well as the Socialists and Communists, the anarchists had the Iberian Anarchist Federation and there was also the anti-Stalinist Workers Party of Marxist Unification (POUM). These radical groups got a greater hearing when workers and peasants were dissatisfied with the cautious measures followed by the Socialists and Communists in government.

Buñuel, though, followed the Communist Party line and supported the Republic from 1936 onwards. Adopting that more defensive tone, Buñuel was alive to the ironic distance between his reputation as a filmmaker and his caution about the unfolding insurrection: ‘With the war in Spain everything we’d thought about, at least everything I’d thought about, became reality: the burning of convents, war, killings, and I was scared stiff, and not only that, I was against it. I’m a revolutionary, but revolution horrifies me. I’m an anarchist, but I’m totally against the anarchists.’

More than just defending the Republic, Buñuel filmed for newsreels and, in time, went to France to work as publicist, diplomat and even spy for his government. As Gubern and Hammond make clear, in politics Buñuel’s actions were always in keeping with the Communist line, defending the Republic against its more radical critics from 1936 until the Fascist victory in 1939. Though Buñuel thought little of the Arniches melodramas he made for Filmofóno, the most successful, Centinela, Alerta! played for 42 weeks in the besieged Madrid, making it the most popular film in Spain at the time.

The two ideals of Stalinist Communism and surrealist experimentation were unhappily married in Buñuel’s subsequent life. Unable to work in an increasingly McCarthyite America, Buñuel slowly rebuilt his reputation as a filmmaker, once again toiling in the mines of cheap melodramas to work up the credit and skills to make the films he wanted to make. Los Olvidados (‘The Forgotten’) took up the cause of street children and won the Grand Prize at Cannes. But it was so disturbing and lacking in redemption that Buñuel’s Communist friends attacked it. Still, he kept up his old friendships with Spanish Communists and Republicans, many of whom were exiled in Mexico. He even visited Ramón Mercader, the Spanish Communist jailed for assassinating Stalin’s greatest Marxist critic, Leon Trotsky, in Mexico. Only much later did Buñuel distance himself from the regime in the Soviet Union.

Does it matter for Buñuel’s art that his politics were compromised? It would have if he had let it, but in the main things, his pushing on with the surrealist struggle against the obvious and beautiful led to some of the most striking and inventive films and a much greater self-consciousness of the meaning of filmmaking itself.

Spike Jonze, Pedro Almodóvar, Penny Woolcock, Charlie Kaufman, Guillermo del Toro and Werner Herzog are all indebted to Buñuel. If anything, Buñuel’s plebeian and rather personalised goading of the well-to-do in The Exterminating Angel and The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, as well as his glee in anti-clericalism and the All Fools Day mob of Viridiana and Los Olvidados, show how he used his social views to dissolve the conventions of film and storytelling, while refusing the mediocre resolutions that were so typical of the mainstream.

Gubern and Hammond have done a great job disinterring the hidden Buñuel from Filmofóno’s back catalogue and many other unexpected sources.

21 Φεβρουαρίου 2013

το πραγματικό

το αληθινό

και το ζωγραφιστό

είναι όρθια

και ίσως μπορούν να αλληλεπιδρούν

το μεγαλο μελανι της χαιδως

είμναι πολύ καλό και μου δημιουργεί πολλές ιδέεσ για συνεχεια

σε πρώτο και δε'[υτερο επίπεδο

ασκηση πιθανη

http://www.youtube-nocookie.com/embed/cS8z4Nv3-k8

Το έργο αυτό απασχόλησε τον Μάνο Χατζιδάκι τα τρία τελευταία χρόνια της ζωής του. Με τον ενδεικτικό υπότιτλο «Η αμαρτία είναι βυζαντινή και ο έρωτας αρχαίος», περιέχει δεκαπέντε μουσικά ποιήματα ερμηνευμένα με λαϊκή καθαρότητα από τον Ανδρέα Καρακότα. Στο πιάνο η Ντόρα Μπακοπούλου.

Το έργο είναι «αφιερωμένο» από τον Μάνο Χατζιδάκι σε όσους ακόμη μπορούν να διαβρωθούν από την μουσική και το τραγούδι.

Το ποίημα είναι του Ντίνου Χριστιανόπουλου

Αδέσποτο στους δρόμους τριγυρνάει

ένα μικρό γαϊδούρι μοναχό,

κανένα χορταράκι μασουλάει

γιατί `ναι πεινασμένο το φτωχό

Κοιτάει τ’ αυτοκίνητα θλιμμένο

και σκύβει το κεφάλι καταγής,

κι εκείνα σταματούνε να περάσει

σα λείψανο μιας άλλης εποχής

Καημένο γαϊδουράκι, που διαβαίνεις

χωρίς ποτέ να χάρηκες στοργή,

ποιος ξέρει σε ποιο δρόμο κάποια μέρα

μια ρόδα θα σου πάρει τη ζωή

20 Φεβρουαρίου 2013

- The migration of concepts from psychoanalysis into the study of visual art.

- The study of artists who are themselves influenced by psychoanalysis.

- Similarities/differences between art and the analytic situation.

- The role of the object in psychoanalytic studies of visual art.

- The role of the viewer in psychoanalytic studies of visual art.

- Combining psychoanalytic ideas with other forms of interpretation.

- Psychoanalysis and the artist-viewer relationship.

- The role of aesthetic experience in psychoanalysis.

- The critique of particular studies which explore artworks psychoanalytically.

- The psychoanalytic interpretation of technical processes of artistic production.

- The relation between visual art and unconscious phantasy (Kleinian) or fantasy (Lacan,

Zizek).

- The use of psychoanalytic ideas/thinkers that have generally been overlooked in art history (e.g. Bion, Winnicott, Laplanche, Milner).

act courses have a strong focus on:

- Dialogues in art, architecture, urbanism, and the production of space

- Interventions in public spaces and the development of anti-monuments and new instruments of collective memory

- Interrogative design, body wear and nomadic devices

- Interfaces between visual art practices, the performative and the sonic

- Experiments with truth – using photographic and time-based media to blur conventional boundaries between documentary and fiction

- Art and Science / Science and Art – research-based artistic practices

download the sound for

19 Φεβρουαρίου 2013

http://embed.ted.com/talks/isabel_allende_tells_tales_of_passion.html

Order to the Chaos of Life: Isabel Allende on Writing

by Maria Popova

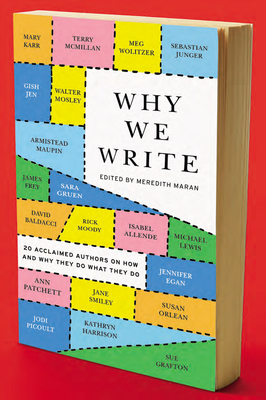

Literary history is ripe with eloquent attempts to answer the ever-elusive question of why writers write. For George Orwell, it resulted from four universal motives. Joan Didion saw it as precious access to her own mind. ForDavid Foster Wallace, it was about fun. Joy Williams found in it a gateway from the darkness to the light. For Charles Bukowski, it sprang from the soul like a rocket. In Why We Write: 20 Acclaimed Authors on How and Why They Do What They Do (public library), which also gave us Mary Karr’s poignant answer, celebrated Chilean American authorIsabel Allende offers one of the most poetic yet practical responses to the grand question.

Literary history is ripe with eloquent attempts to answer the ever-elusive question of why writers write. For George Orwell, it resulted from four universal motives. Joan Didion saw it as precious access to her own mind. ForDavid Foster Wallace, it was about fun. Joy Williams found in it a gateway from the darkness to the light. For Charles Bukowski, it sprang from the soul like a rocket. In Why We Write: 20 Acclaimed Authors on How and Why They Do What They Do (public library), which also gave us Mary Karr’s poignant answer, celebrated Chilean American authorIsabel Allende offers one of the most poetic yet practical responses to the grand question.

I need to tell a story. It’s an obsession. Each story is a seed inside of me that starts to grow and grow, like a tumor, and I have to deal with it sooner or later. Why a particular story? I don’t know when I begin. That I learn much later. Over the years I’ve discovered that all the stories I’ve told, all the stories I will ever tell, are connected to me in some way. If I’m talking about a woman in Victorian times who leaves the safety of her home and comes to the Gold Rush in California, I’m really talking about feminism, about liberation, about the process I’ve gone through in my own life, escaping from a Chilean, Catholic, patriarchal, conservative, Victorian family and going out into the world.

It’s so important for me, finding the precise word that will create a feeling or describe a situation. I’m very picky about that because it’s the only material we have: words. But they are free. No matter how many syllables they have: free! You can use as many as you want, forever.

I try to write beautifully, but accessibly. In the romance languages, Spanish, French, Italian, there’s a flowery way of saying things that does not exist in English. My husband says he can always tell when he gets a letter in Spanish: the envelope is heavy. In English a letter is a paragraph. You go straight to the point. In Spanish that’s impolite. Reading in English, living in English, has taught me to make language as beautiful as possible, but precise. Excessive adjectives, excessive description — skip it, it’s unnecessary. Speaking English has made my writing less cluttered. I try to readHouse of the Spirits now, and I can’t. Oh my God, so many adjectives! Why? Just use one good noun instead of three adjectives.

Fiction happens in the womb. It doesn’t get processed in the mind until you do the editing.

I start all my books on January eighth. Can you imagine January seventh? It’s hell. Every year on January seventh, I prepare my physical space. I clean up everything from my other books. I just leave my dictionaries, and my first editions, and the research materials for the new one. And then on January eighth I walk seventeen steps from the kitchen to the little pool house that is my office. It’s like a journey to another world. It’s winter, it’s raining usually. I go with my umbrella and the dog following me. From those seventeen steps on, I am in another world and I am another person. I go there scared. And excited. And disappointed — because I have a sort of idea that isn’t really an idea. The first two, three, four weeks are wasted. I just show up in front of the computer. Show up, show up, show up, and after a while the muse shows up, too. If she doesn’t show up invited, eventually she just shows up.

I correct to the point of exhaustion, and then finally I say I give up. It’s never quite finished, and I suppose it could always be better, but I do the best I can. In time, I’ve learned to avoid overcorrecting. When I got my first computer and I realized how easy it was to change things ad infinitum, my style became very stiff.

My daughter, Paula, died on December 6, 1992. On January 7, 1993, my mother said, ‘Tomorrow is January eighth. If you don’t write, you’re going to die.’ She gave me the 180 letters I’d written to her while Paula was in a coma, and then she went to Macy’s. When my mother came back six hours later, I was in a pool of tears, but I’d written the first pages of Paula. Writing is always giving some sort of order to the chaos of life. It organizes life and memory. To this day, the responses of the readers help me to feel my daughter alive.

Storytelling and literature will exist always, but what shape will it take? Will we write novels to be performed? The story will exist, but how, I don’t know. The way my stories are told today is by being published in the form of a book. In the future, if that’s not the way to tell a story, I’ll adapt.

- It’s worth the work to find the precise word that will create a feeling or describe a situation. Use a thesaurus, use your imagination, scratch your head until it comes to you, but find the right word.

- When you feel the story is beginning to pick up rhythm—the characters are shaping up, you can see them, you can hear their voices, and they do things that you haven’t planned, things you couldn’t have imagined—then you know the book is somewhere, and you just have to find it, and bring it, word by word, into this world.

- When you tell a story in the kitchen to a friend, it’s full of mistakes and repetitions. It’s good to avoid that in literature, but still, a story should feel like a conversation. It’s not a lecture.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hXY_ML3oMwI&feature=share&list=AL94UKMTqg-9AOmHp-ioQW7kqRYDHkVbPo

http://www.archiact.com/content/links

http://thefunambulist.net/2012/06/30/foucault-episode-7-questioning-the-heterotopology/#more-11032

http://arenaofspeculation.org/2012/11/25/re-lifta/

Love is the collective urge to seize freedom by any means necessary.

“Foucault and the critique of our present:

Reworking the Foucauldian tool-box”

A workshop organized with the support of the Department of

Politics at Goldsmiths and of mf/materiali foucaultiani

Orazio Irrera

(Paris VII / materiali foucaultiani)

“Toward a Postcolonial

Genealogy of Environmental

Subjectivities”

February 21 , 5-7 pm

(RHB) 141

Goldsmiths University of London

Contacts:

Yari Lanci: yari.lanci@gmail.com

Martina Tazzioli: martinatazzioli@yahoo.i

8 RESPONSES TO # FOUCAULT /// EPISODE 7: QUESTIONING THE HETEROTOPOLOGY

LEAVE A REPLY

steve reich-drawings

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qxlKqxAB4ms&feature=share&list=AL94UKMTqg-9AOmHp-ioQW7kqRYDHkVbPo

Drawings by Michaël Borremans

http://www.archiact.com/content/6th-gates-shines-no-more

Concentrating on the latter, and taking up Elden’s notion of Foucault’s use of space as a tool of analysis, I explore how Foucault’s intense study of modern literature, particularly Roussel and Blanchot, contributes to underlying modes of spatialisation that drive his study of the history of clinical medicine, as well as the complex explanation of his archaeological approach.

Following Deleuze, I argue that these spatialisations are both the instrument and the object of his studies. They generate devices and tactics for dismantling established methods of analysis and manifest the powerful, multiple effects of discourse, whilst remaining meticulously at the level of description. Restricted material:

18 Φεβρουαρίου 2013

or the last ‘episode’ of this series of articles around the work of Michel Foucault, I would like to evoke the second favorite Foucauldian concept (the first one being the panopticon) that architects like to use, the heterotopia. As a matter of fact, this term, dropped in the architectural discourse became almost an argument in itself like an incantation – and I plead guilty about that myself for having used it often without any real meaningful deepening. The responsibility for that can only be half devolved to architects as this concept has been only loosely defined by Foucault himself, who was probably not considering it as one of his strongest inventions.

14 Φεβρουαρίου 2013

12 Φεβρουαρίου 2013

Koskela: ‘Cam Era’

http://www.surveillance-and-society.org/journalv1i3.htm

Deriving from Foucault’s work, space is understood to be crucial in explaining social power relations.

However, not only is space crucial to the exercise of power but power also creates a particular kind of

space. Through surveillance cameras the panoptic technology of power is electronically extended. The

article examines parallelisms and differences with the Panopticon and contemporary cities: visibility,

unverifiability, contextual control, absence of force and internalisation of control. Surveillance is examined as an emotional event, which is often ambivalent or mutable, without sound dynamic of security and

insecurity nor power and resistance. Control seems to become dispersed and the ethos of mechanistic

discipline replaced by flexible power structures. Surveillance becomes more subtle and intense, fusing

material urban space and cyberspace. This makes it impossible to understand the present forms of control

via analysing physical space. Rather, space is to be understood as fundamentally social, mutable, fluid and

unmappable – ‘like a sparkling water’. The meaning of documentary accumulation changes with the ‘digital

turn’ which enables social sorting. The popularity of ‘webcams’ demonstrate that there is also fascination in

being seen. The amount of the visual representations expands as they are been circulated globally.

Simultaneously the individuals increasingly ‘disappear’ in the ‘televisualisation’ of their lives. The

individual urban experience melts to the collective imagination of the urban. It is argued that CCTV is a

bias: surveillance systems are presented as ‘closed’ but, eventually, are quite the opposite. We are facing

‘the cam era’ – an era of endless representations.

The major effect of the Panopticon is, in Foucault’s words (1977: 201), ‘to induce in the

inmate a state of conscious and permanent visibility that assures the automate functioning

of power’. The emphasised meaning of visibility is perhaps the most obvious and often

recognised panoptic principle. The basic nature of the exercise of disciplinary power

‘involves regulation through visibility’ (Hannah, 1997a: 171). ‘Power is exercised

through ‘the “eye of power” in the disciplinary gaze’ (Ramazanoglu, 1993: 22). To be

able to see offers the basic condition for collecting knowledge, for being ‘in control’. In

urban space ‘absolute visibility is legitimated with the claim and the guarantee of

absolute security’ (Weibel, 2002: 207). Both in the Panopticon and in the space of

surveillance, social contact is – most often – reduced to visual (Koskela, 2002). It is,

however, worth noting that many surveillance systems include loudspeakers which can

mediate messages to the public – as per the idea of ‘a speaking tube system’ in the

Panopticon (Ainley, 1998: 88

‘Cam Era’ – the contemporary urban

Panopticon.*

Hille Koskela1

Koskela: ‘Cam Era’

Surveillance & Society 1(3) 297

He writes about ‘space of our dreams’, ‘internal’ and ‘external’ space, and ‘a space that

can be flowing like a sparkling water’. Foucault glorifies space – by talking about ‘the

epoch of space’ (1986: 22) which is replacing the important role of time (i.e. history) –

but simultaneously builds concepts that are disengaged from architecture and come close

to the idea of the social production of space. Rather than politics and economy (which

have quite often been the basis for the argument that space is socially produced) he

describes the spaces created by human habits, cultures and religions. This means that

Foucault’s ideas come close to Lefebvre’s concept of ‘representational space’ (1991: 39)

which he describes as ‘space as directly lived through its associated images and symbols,

and hence the space of “inhabitants” and “users” […] space which the imagination seeks

to change and appropriate’. Unfortunately, this work was never published by Foucault

himself and the concepts used were never developed further.

In analysing the parallelisms and differences with the Panopticon and contemporary

cities, it is important to acknowledge that urban space is far more complex than the

concept of space in Foucault’s interpretations of the prison. In cities, people may

sometimes be metaphorically imprisoned but, nevertheless, they are not under isolation

but quite the opposite: a city is a space of endless encounters. Whereas a prison is an

extremely homogenous space, a city is full of diversity. This diversity – of both spaces

and social practices – makes it impossible to compare urban space simply and directly to

the Panopticon. ‘Too much happens in the city for this to be true’, as Soja (1996: 235)

points out. However, there are several principles, characteristic to the mechanism of the

Panopticon, which are clearly present in the surveillance of cities. Some are almost selfevident

some more unexpected, but yet, they are all worth specifying.

‘A dream of a transparent society’

The major effect of the Panopticon is, in Foucault’s words (1977: 201), ‘to induce in the

inmate a state of conscious and permanent visibility that assures the automate functioning

of power’. The emphasised meaning of visibility is perhaps the most obvious and often

recognised panoptic principle. The basic nature of the exercise of disciplinary power

‘involves regulation through visibility’ (Hannah, 1997a: 171). ‘Power is exercised

through ‘the “eye of power” in the disciplinary gaze’ (Ramazanoglu, 1993: 22). To be

able to see offers the basic condition for collecting knowledge, for being ‘in control’. In

urban space ‘absolute visibility is legitimated with the claim and the guarantee of

absolute security’ (Weibel, 2002: 207). Both in the Panopticon and in the space of

surveillance, social contact is – most often – reduced to visual (Koskela, 2002). It is,

however, worth noting that many surveillance systems include loudspeakers which can

mediate messages to the public – as per the idea of ‘a speaking tube system’ in the

Panopticon (Ainley, 1998: 88).

The Panopticon embodies the power of the visual. Visibility connotates with power.

Within surveillance, visibility does not just have an important role but its meaning

overpowers other senses. This has consequences, as I shall argue, to how prejudice is

structured. By increasing surveillance ‘[a] dream of a transparent society’ (Foucault,

1980:152), a society where everything is subjugated to visual control, has almost been

Panopticon

Morals reformed— health preserved — industry invigorated — instruction diffused — public burthens lightened — Economy seated, as it were, upon a rock — the gordian knot of the poor law not cut, but untied — all by a simple idea in Architecture!

Πίνακας περιεχομένων[Απόκρυψη] |

Περιγραφή του Κτιρίου [Επεξεργασία]

Η Λογική του Σχεδιασμού [Επεξεργασία]

Η Αρχιτεκτονική Τομή [Επεξεργασία]

Μια Σύγχρονη Εκδοχή του Πανοπτικού [Επεξεργασία]

Αναφορές [Επεξεργασία]

- ↑ Η ιδέα του Πανοπτικού ανήκει στον αδελφό του Μπένταμ, Samuel, ο οποίος σκόπευε αρχικά να την εφαρμόσει σε μεγάλα εργαστήρια και βιοτεχνίες. Ο Τζέρεμι Μπένταμ έδωσε μορφή στην ιδέα του αδελφού του, δημιουργώντας παραλλαγές του ίδιου κτηρίου και δημοσιεύοντάς τις στο βιβλίο του Panopticon: or, the Inspection-House το 1787. Το βιβλίο κυκλοφορεί ακόμα από διάφορους εκδοτικούς οίκους.

- ↑ Τζέρεμι Μπένταμ, σελ 40

- ↑ Μισέλ Φουκώ, Επιτήρηση και τιμωρία. Η γέννηση της φυλακής, Εκδόσεις Ράππα, Αθήνα 1989, σελ. 265

- ↑ Μισέλ Φουκώ, Επιτήρηση και τιμωρία. Η γέννηση της φυλακής, Εκδόσεις Ράππα, Αθήνα 1989, σελ. 266

- ↑ Μισέλ Φουκώ], Επιτήρηση και τιμωρία. Η γέννηση της φυλακής, Εκδόσεις Ράππα, Αθήνα 1989, σελ. 266

- ↑ Μισέλ Φουκώ, Επιτήρηση και τιμωρία. Η γέννηση της φυλακής, Εκδόσεις Ράππα, Αθήνα 1989, σελ. 266

- ↑ Winfried Reebs, Φυλακές και αρχιτεκτονική, Α/μηχανία 1988, σελ. 22

Peter

http://www.heterotopiastudies.com/

In contrast, Porphyrios uses the concept in a thorough revaluation of Alvar Aalto’s architecture (1982). He argues that heterotopia helps to identify a fundamental category of Aalto’s design method that opposes trends within what Porphyrios calls ‘homotopic’ modernism (110). Discontinuity, gaps and fragments are embraced rather than the smooth continuities of modernism. A ‘heterotopic sensibility’ introduces difference rather than drawing elements together and juxtaposes dissimilar things in order to produce ‘cohesion through adjacency’. Heterotopic organisation is able to fragment and relate simultaneously, an accretional process:

Peter

http://www.heterotopiastudies.com/