Digital Technology as a Tool

Process v. Production: What are the distinctive characteristics of digital

media reflected in its language and aesthetic?

• Multiple kinds of manipulation

• Analog v. digital

• Real v. unreal

• Blurring distinctions between different media and seamless combination of

art forms

• Recontextualization through appropriation and collage (dada, cubism,

surrealism)

• Relationship between copy and original

INTRODUCTION NOTES 2DFIELD

Screen Space: fixed borders that defines the new aesthetic characteristics

• Aspect ratio: relationship of screen width to screen height

• Horizontal orientation

• Standard ratios

• Standard TV / computer screens adopted 4×3 ratio of early motion

pictures (1.33:1 ratio)

• Digital / HDTV – 16×9 (5.33×3 or 178:1)

• Standard wide screen of motion pictures (5.33×3 or 1.85:1)

• Panavision / Cinemascope has extremely wide aspect ratio – 7×3

(2.35:1)

• Wide-screen – format of most U.S. films

• Framing

• 4×3 frame (film standard was established as early as 1889)

• advantage is that the difference between screen width & height does not emphasize one dimension over another

• works well with close-ups

• 16×9 frame

• have to pay more attention to the peripheral pictorial elements/events

• Changing the Aspect Ratio

• Matching aspect ratio

• Letterboxing: wide screen letterbox is created by showing the whole

width & height of the original format, and masking the top and

bottom of the screen with black, white, or colored bands called

dead zones

• Pillarboxing: fitting a standard 4×3 image onto a 16×9 screen

(vertical pillar bars)

• Cutting, stretching, squeezing

• Secondary Frames

• Masking – blacking out both sides of the screen (ex. D.W. Griffith – Intolerance)

• Multiple screens<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<

• Moving camera<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<(panning, tilting, arcing, dollying, pedding, trucking)

• Object size > context<<<<<<<<

• Knowledge of object<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<

• Relation to screen area<<<

• Environment & scale<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<

• Reference to a person<<

• Image size

• Size constancy – we perceive people and their environments as normal sized regardless of screen size

• Image size & relative energy–<<<<

• Power of image is related to screen size & format<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<

• People & things

Editing Aesthetics

Continuity Style Editing

• Jump Cut: edits that reveal or present themselves as discontinuous jumps in time, action, or space

• Whenever possible vary the horizontal field of view between successive shots. When Shooting events & activities think: wide shot, medium shot, close-up. Your first shot should typically be a master, cover, or

establishing shot, then tighten your shots as you continue to tape.

• TV is a close-up medium. My beginning shooters frame shots too wide and include too much headroom. Always try to capture close-ups of events, but also be conscious of the hazards of shallow depth of field,

framing & composition, and excessive camera shake.

• While varying the horizontal field of view, also attempt to vary the angle of approach.

• Repeating actions, or shooting repetitive actions varying the horizontal field of view and the angle of approach allow you to build matched action edits.

• Let subjects in motion move into and out of stationary frames.

• Shots with secondary movement should begin and end at rest.(panning, tilting, arcing, dollying,

pedding, trucking)

• Classical editing stratregies:

o Eyeline match edits

o Split edits (L & J edits)

o When editing dialogue allow for proper breath space

o Cut in and cut out edits

o Parallel scene edits

o Flash back edits

o Cutting to the beat

o Cutting on dialogue

o Montage

o Dissolve, fade, wipe transitions

o Compositing and collage

theory

—-photocopies/translations (>>>>)

video in relation to space// documntaries//montaz

χώροι..

//eliason/turel/serra/Dan Ggraham

/dia c. roof—

/body position – space psychology -well’s orientation/

4delaments- rythm – examples damian’s hirst/swiss/sound vibration installations

network libraries/archives-

the object as an art object (duchamp- the rotoscope)

http://www.dezeen.com/2013/01/19/the-silence-room-at-selfridges-by-alex-cochrane-architects/

http://www.architizer.com/en_us/blog/dyn/72610/life-on-the-edge-a-photographers-self-portraits-finds-her-straddling-the-void/#.UPo0mh26eft

πολύ ενδιαφέρων ξεκίνημα,Νίκο όμως θα μας εξηγήσεις από κοντά γιατί είναι τετράγωνο αντικείμενο …. αν παραπέμπει ακόμα στο κουτί της Πανδώρας η έχει αυτονομηθεί νοηματικά? και άλλα … νομίζω ότι είναι καλή ιδέα να φτιάξεις ένα νέο blog δικό σου για αυτό το έργο ειδικά αφού το επεξεργάζεσαι για καιρό… και να κάνεις πιο αναλυτικές αναρτήσεις που να αφορούν την διαδικασία της έρευνας σου σε σχέση με τα πλαστικά στοιχεία του έργου <<<<< όπως χρώμα- χρόνος//αντικείμενο -χώρος//κλπ) <<<<και το πως αυτά επικοινωνούν τις σκέψεις σου για το χρόνο…έχει σημασία η απόσταση του θεατή? έχει σημασία η θερμοκρασία του χώρου και πως την ελέγχεις? αν δεν την ελέγχεις τι εποχή και που είναι οι ιδανικές συνθήκες έκθεσης και γιατί κλπ? νομίζω ότι το υλικό της διαδικασίας πρέπει να είναι περισσότερο και να αποκαλύπτει καλύτερα το ερευνητικό κομμάτι η καλύτερα την εικαστική τεκμηρίωση της κατασκευής σου .. στο blog έχουν σημασία να καταγράφονται – και που το παρουσιάζεις – το πραγματοποιείς το έργο -αν και αυτό είναι αντικείμενο της ερευνάς σου και νομίζω ότι είναι…..θα τα πούμε και από κοντά..

μουσική

μια ακόμα μάσκα

http://loloro.com/home.html

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-qM3oXDng6s

Augé, Marc (1992) Non-lieux. Introduction á une anthropologie de la surmodernité. Paris: Seuil

Baudrillard, Jean (1982) A l’ombre des majorités silencieuses. Paris

Burgess, Anthony (1989) The Devil’s Mode. New York: Pocket Books

Friedman, Jonathan (1991) Narcissism, roots and postmodernity: the constitution of selfhood in the global crisis. In Scott Lash and Jonathan Friedman, eds., Modernity and Identity, pp. 331-366. Oxford: Blackwell

Geertz, Clifford (1973) Deep Play: Notes on the Balinese cockfight. In Geertz, The Interpretation of Cultures, pp. 412-454. New York: Basic Books

Giddens, Anthony (1990) The Consequences of Modernity. Cambridge: Polity

– (1991) Modernity and Self-Identity. Cambridge: Polity

Hannerz, Ulf (1990) Cosmopolitans and locals in world culture. In Mike Featherstone, ed., Global Culture. Nationalism, Globalization and Modernity, pp. 237-252. London: SAGE

– (1992) The withering away of the nation? Paper delivered at the conference Defining the National. Bjärsjölagård, Sweden, 26-28 April, 1992

Kapferer, Bruce (1986) The ritual process and the problem of reflexivity in Sinhalese demon exorcism. In John MacAloon, ed., Rite, Drama, Festival, Spectacle, pp. 179-207. Ithaca: Cornell University Press

Χώρος

Η οργάνωση του χώρου εντός του αεροδρομίου έχει συνοπτικά εκτιμηθεί. Αλλά προφανώς, τα πιο ενδιαφέροντα χωρικά χαρακτηριστικά του αεροδρομίου είναι (i) η τοποθεσία του «εκτός του κοινωνικού χώρου» και (ii) η «σχετικοποίηση» των χωρικών συσχετισμών της κοινωνικής ζωής που υποβάλλονται από το ταξίδι.

Ο Augé, σε έναν πολιτισμικό απολογισμό του εναέριου ταξιδιού, επισημαίνει την αβίαστη αποτελεσματικότητα, την μοντερνιστική άνεση και την απρόσωπη διάσταση του συγκεκριμένου μέσου μεταφοράς. Επιπροσθέτως, θα είχεαξία η επισκόπηση των επιπτώσεων του ταξιδιού στο χώρο. Συγγραφείς εθνιστικών κσι μοντερνιστικών θεμάτων και συχνά επισημαίνουν τη σημασία της μόρφωσης, της εκπαίδευσης των μαζών και των χαρτών στη δημιουργία ταυτοτήτων για αόριστες έννοιες όπως το έθνος. Ένα ενδιαφέρον ερώτημα επί αυτού του συσχετισμού είναι το τι είδους ταυτότητα (αν υπάρχει) και ποια αίσθηση χώρου μπορεί να ενθαρρύνουν τακτικά εναέρια ταξίδια. Είναι προφανές και συχνά επισημαίνεται σε τυπικές συζητήσεις πως η ψυχολογική αίσθηση της απόστασης αλλάζει ή διαστρεβλώνεται σημαντικά με τα τακτικά ταξίδια και με την αναδίπλωση(?!) της απόστασης στις ώρεςτης πτήσης.

Ἡσύγχρονη «θεολογία» τῆς αἱρέσεως τοῦΟἰκουμενισμοῦ ἔναντί τῶν Ἱερῶν Κανόνων.

συγκόλληση.

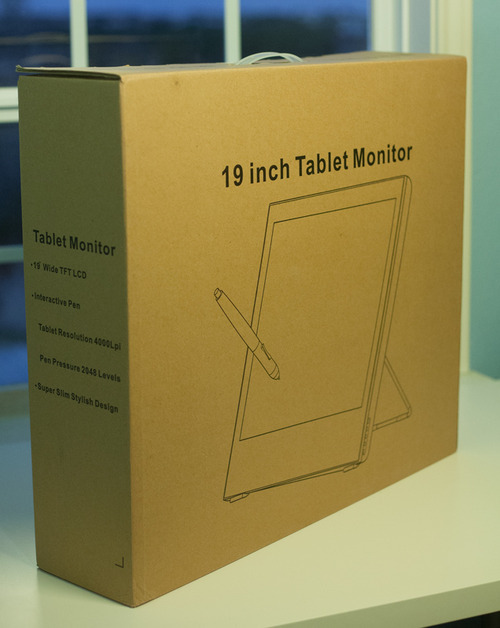

Αντικείμενο του μαθήματος είναι η διερεύνηση των αισθητικών, τεχνικών και γνωστικών δυνατοτήτων των πολυμέσων. Το μάθημα χρησιμοποιεί τις καταγραφές του αστικού περιβάλλοντος που έχουν παραχθεί το προηγούμενο εξάμηνο με τη μορφή διαφορετικών ψηφιακών αντικειμένων (εικόνας, ήχου, κειμένου, διαγραμμάτων, σχεδίων, κ.α.), με σκοπό την οργάνωση και παρουσίασή τους σ’ ένα ενιαίο ψηφιακό περιβάλλον. Μας ενδιαφέρει η επικοινωνία της εμπειρίας του αστικού περιβάλλοντος μέσα από σύνθετες διαδραστικές και αφηγηματικές μορφές. Συζητούνται θεωρητικές έννοιες όπως η δια δραστικότητα, το υπερκείμενο, η αφήγηση, η βάση δεδομένων, καθώς και έργα τέχνης που βασίζονται σε πολυμεσικές και διαδικτυακές εφαρμογές (cd-rom, net.art, κ.α.) Σκοπός του μαθήματος είναι η διερεύνηση και η ανακάλυψη μεθόδων ανάλυσης και παρουσίασης που αποσαφηνίζουν το έργο και την ιδέα

http://ktelstation.blogspot.gr/2007/07/blog-post.html

Το μάθημα είναι εργαστηριακό και διεξάγεται με διαλέξεις, παρουσιάσεις και κριτική εργασιών

Vasilys Bouzas received his Masters (MFA) in Computer Graphics and Interactive Media from the Pratt Institute, New York after he was awarded with two scholarships from the Greek state and the Fulbright Foundation (1997). He holds a BFA from the Athens School of Fine Arts and BSc in engineering from the National Technical University in Athens. During the years 1997 to 2003, he studied, worked and taught in New York in the fields of design and implementation of digital applications. He has participated in exhibitions and competitions in Greece and abroad. Since 2003, he is based in Greece where he has been working as a designer and artist. He has worked in art education at the Department of Architecture, University of Patras (2004-2011) and he currently works at the Department of Applied Arts, University of Western Macedonia, Greece.

mapping projections

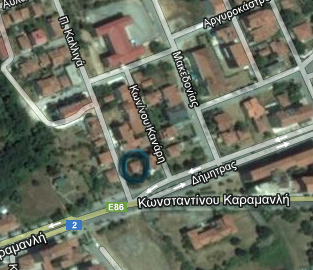

To +σεμινάριο περιλαμβάνει την εξερεύνηση επιλεγμένων τόπων στο νησί

Το σεμινάριο περιλαμβάνει την ανάπτυξη μεθόδων εξερεύνησης και χαρτογράφησης ανθρωπογεωγραφικών χαρακτηριστικών επιλεγμένων χώρων (κυρίως τόπων εργασίας;)

,

μεθόδων σύνθεσης και ταξινόμησης της οπτικοακουστικής πληροφορίας,

μεθόδους σύνθεσης κινούμενης εικόνας (3d animations, 2d animations, motion capture, tracking motion, stabilizing, alpha channels, κ.λπ.)

με στόχο τον σχεδιασμό και τη δημιουργία mapping projections

Από την εμπειρία του περσινού workshop

που ήταν πολύ διαφορετικό workshop από το προπέρσινο που έγινε στη Κέρκυρα

θα μπορούσα να εν ταχθώ στις ομάδες επεξεργασίας δισδιάστατου και τρισδιάστατου σχεδιασμού

και σύνθεσης κινούμενης εικόνας (2d η 3d )

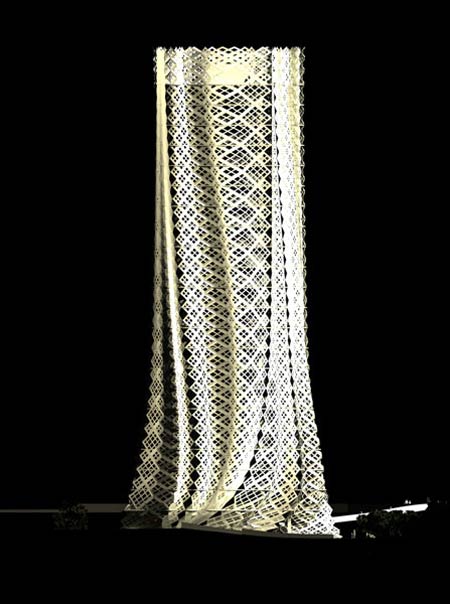

Σκοπός του μαθήματος είναι η διερεύνηση και η ανακάλυψη μεθόδων ανάλυσης και παρουσίασης (πέραν των γνωστών παραδοσιακών μεθόδων), που αποσαφηνίζουν το αρχιτεκτονικό έργο ή την ιδέα (abstract). Οι νέες τεχνολογικές αναλύσεις υποστηρίζουν σύνθετα σχέδια και κτιριακά προγράμματα απεικονίζοντας τα, διευκολύνοντας την αξιολόγηση τους, διευρύνοντας και ενδυναμώνοντας σε επίπεδο σύνθεσης τις φοιτητικές εργασίες. Επίσης θα γίνει εισαγωγή σε βασικές έννοιες-λειτουργίες του εικονικού χώρου όπως οι πρωτογενείς κινήσεις χαρακτήρων η αντικειμένων, μέθοδοι rendering, motion dynamics, hierarchical animation, inverse kinematics κ.α. καθώς και η δημιουργία στο διαδίκτυο, εικονικών και πραγματικών χώρων, με δυσδιάστατους και τρισδιάστατους τρόπους απεικόνισης και οργάνωσης της πληροφορίας.

1. Αναγνώριση της περιοχής, ανάλυση και αφαιρετική αναπαράσταση. Πως αντιλαμβανόμαστε το φυσικό και τεχνητό τοπίο σαν αρχή ή τέλος της πόλης. Ποια φυσικά χαρακτηριστικά εισχωρούν στη ζωή της πόλης. Σχέσεις μεταξύ στοιχείων, μερών και συνόλων. Γνωριμία με τα εργαλεία (3D Studio, FormZ, Maya, Photoshop). Από το 2D στο 3D. Ζητείται η κατασκευή ψηφιακών μοντέλων αναπαράστασης σε διάφορες κλίμακες και βαθμούς λεπτομερειών.

2. Ποιες ποιότητες της παραπάνω ανάλυσης συντελούν στη διαμόρφωση αρχιτεκτονικής πρότασης για τη περιοχή. Μετασχηματισμοί στην πόλη και στον εικονικό χώρο. Άσκηση μετασχηματισμών στερεών και διαμόρφωση πρότασης. Εισαγωγή στη κινούμενη εικόνα –animation.

3. Σχεδιασμός, αναπαράσταση και παρουσίαση.

landscape and arch.

landscape and arch.