29 Απριλίου 2009

Antony Gormley

Antony Gormley was born in London in 1950. Upon completing a degree in archaeology, anthropology and the history of art at Trinity College, Cambridge, he travelled to India, returning to London three years later to study at the Central School of Art, Goldsmiths College and the Slade School of Art.

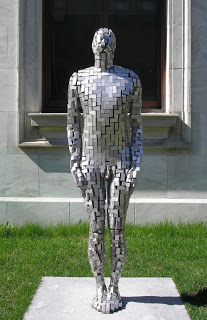

Over the last 25 years Antony Gormley has revitalised the human image in sculpture through a radical investigation of the body as a place of memory and transformation, using his own body as subject, tool and material. Since 1990 he has expanded his concern with the human condition to explore the collective body and the relationship between self and other in large-scale installations like Allotment, Critical Mass, Another Place, Domain Field, and Inside Australia. His recent work increasingly engages with energy systems, fields and vectors, rather than mass and defined volume, evident in works like Clearing, Blind Light, Firmament and Another Singularity.

Antony Gormley’s work has been exhibited extensively, with solo shows throughout the UK in venues such as the Whitechapel, Tate and the Hayward galleries, the British Museum and White Cube, and internationally at museums including the Louisiana Museum in Humlebaek, the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington DC, the Irish Museum of Modern Art in Dublin, and the Kölnischer Kunstverein in Germany. Blind Light, a major solo exhibition of his work, was held at the Hayward Gallery in 2007.

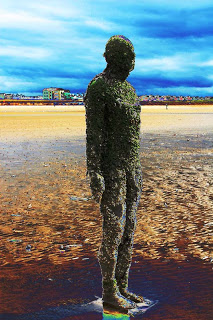

He has participated in major group shows such as the Venice Biennale and the Kassel Documenta 8. His Field has toured America, Europe and Asia. Angel of the North and, more recently, Quantum Cloud on the Thames in Greenwich are amongst the most celebrated examples of contemporary British sculpture. One of his key installations, Another Place, is to remain permanently on display at Crosby Beach, Merseyside.

He was awarded the Turner Prize in 1994 and the South Bank Prize for Visual Art in 1999 and was made an Order of the British Empire (OBE) in 1997. In 2007 he was awarded the Bernhard Heiliger Award for Sculpture. He is an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Institute of British Architects, Trinity College, Cambridge and Jesus College, Cambridge, and has been a Royal Academician since 2003.

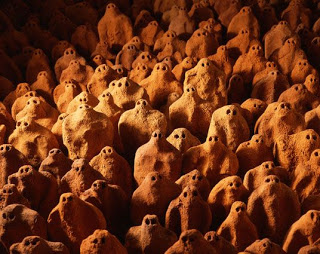

Field

(1991 – 2003)

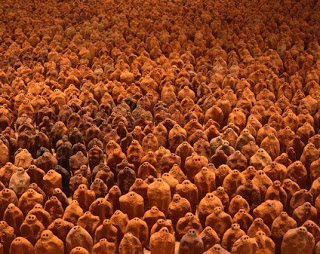

From the beginning I was trying to make something as direct as possible with clay: the earth.

I wanted to work with people and to make a work about our collective future and our responsibility for it. I wanted the art to look back at us, its makers (and later viewers), as if we were responsible – responsible for the world that it (the work Field) and we were in. I have made it with help five times in different parts of the world.

The most recent is from Guangzhou, China, and was exhibited in Guangzhou, Beijing, Shanghai and Chongqing in 2003. It’s made from one hundred and twenty-five tons of clay energised by fire, sensitised by touch and made conscious by being given eyes.

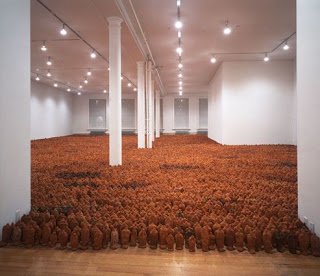

The 200,000 body-surrogates completely occupy the space in which they are installed, taking the form of the building and excluding us, but allowing visual access.

It is always seen from a single threshold. The dimensions of the viewing area are equivalent to no less than one sixth of the total floor area of the piece. This viewing area is completely empty.

The viewer then mediates between the occupied and unoccupied areas of a given building. I like the idea of the physical area occupied being put at the service of the imaginative space of the witness.

Makers’ Instructions

I gave these instructions to the makers:

Take a hand-size ball of clay, form it between the hands, into a body surrogate as quickly as possible. Place it at arm’s length in front of you and give it eyes.

It was important that it was through the repeated action of touching, forming, placing apart from the body and making conscious, that each person found their own form. The extraordinary thing was the distinctiveness of the forms that were found.

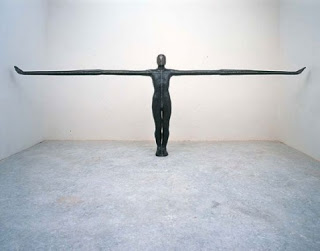

Angel of the North

Gateshead (1998)

Is it possible to make a work with purpose in a time that demands doubt? I wanted to make an object that would be a focus of hope at a painful time of transition for the people of the north-east, abandoned in the gap between the industrial and the information ages.

The work is made of corten steel, weighs 200 tonnes and has 500 tonnes of concrete foundations. The mound near the A1 motorway which was the designated site of the sculpture was made after the closure of the Lower Tyne Colliery, out of the destroyed remains of the pithead baths. It is a tumulus marking the end of the era of coal mining in Britain.

The Angel resists our post-industrial amnesia and bears witness to the hundreds and thousands of colliery workers who had spent the last three hundred years mining coal beneath the surface.

The scale of the sculpture was essential given its site in a valley that is a mile and a half a mile wide, and with an audience that was travelling past on the motorway at an average of 60 miles an hour.

The exo-skeleton seemed the best solution for transforming a self-supporting fibreglass and lead structure into an object 10 times life-size, or 20 m high. It uses the Tyneside engineering vernacular of ships and the Tyne Bridge, to produce a strong structure that would withstand the prevailing south-easterly winds. This has the added advantage of giving the form a strong surface articulation that deals equally well with volume and light.

We made a series of models to work out how this was going to work: the challenge was to transfer a rib structure that radiates from a central axis in the bodyform onto the wings, and the solution was to have an increasing distance between the ribs, suggesting a broadcasting of energy.

The work stands, without a spolight or a plinth, day and night, in wind, rain and shine and has many friends. It is a huge inspiration to me that the Angel is rarely alone in daylight hours, and as with much of my work, it is given a great deal through the presence of those that visit it.

12 Απριλίου 2009

//www.youtube.com/get_playerΜ’αυτό το βίντεο θέλησα να παρουσιάσω έναν απο τους τρόπους με τους οποίους εκδηλώνει ένας άνθρωπος το φαινόμενο της συναισθησίας… Η δημιουργία του έγινε σε πρόγραμμα δημιουργίας τρισδιάστατων αντικειμένων (3D Max) και η κίνηση που του προσαρμόστηκε προέρχεται απο εργαλεία του ίδιου προγράμματος.

Το θέμα που διάλεξα να προβάλλω είναι και ο τρόπος με τον οποίο εκδηλώνεται σε μένα η συναισθησία. Μου δίνει την δυνατότητα να ταυτίζω τους αριθμούς και κάποιες λέξεις, των οποίων η ερμηνεία δεν έχει να κάνει με οτιδήποτε που έχει δική του εικόνα, με χρώματα. Για παράδειγμα η λέξη ήλιος συνδιάζεται αυτόματα με το κίτρινο ή πορτοκαλί χρώμα όπως και η λέξη αίμα με το κόκκινο, αντίθετα οι λέξεις αυτοπεποίθηση, πόνος, ελπίδα κ.ο.κ ως έννοιες δεν έχουν εικόνα έτσι ο κάθε άνθρωπος τις εκλαμβάνει με διαφορετικό και υποκειμενικό τρόπο κάθε φορα. Ο δικός μου τρόπος είναι “χρωματικός”.

9 Απριλίου 2009

8 Απριλίου 2009

SIGNATURE

KAI NAI….Η ΥΠΟΓΡΑΦΗ ΣΟΥ ΕΧΕΙ ΣΗΜΑΣΙΑ…ΕΝΑ ΑΠΟ ΤΑ ΠΙΟ ΩΡΑΙΑ ΑΝΙΜΑΤΙΟΝ ΠΟΥ ΕΧΩ ΔΕΙ(ΜΟΥΣΙΚΗ ΦΟΒΕΡΗ…)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ehKA8vi2EbE

MICHAL ROVNER REAL VIDEO

MICHAL ROVNER

-

MICHAL ROVNER

-

Born in 1957 in Tel Aviv, Michal Rovner studied cinema, television, photography, philosophy, and art. Since moving to New York in 1987, Rovner has seen her work shown extensively, including at The Art Institute of Chicago; the Tate Gallery, London; P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center, New York; the Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; and The Museum of Modern Art, New York. The Whitney Museum of American Art in New York hosted a mid-career retrospective in the summer.

Rovner, Michal

Rovner, Michal: “Michal Rovner: Fields

Essays by Rιgis Durand, Sylvθre Lotringer and Mordechai Omer.

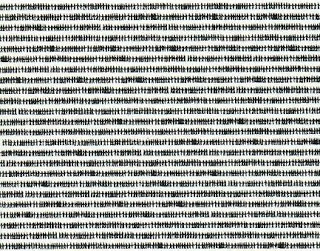

Video artist Michal Rovner’s unique and ever-expanding alphabet is built of tiny depictions of the human figure. Fields documents her work in this vein over the past three years, including Data Zone, which combines the sculpture and video from her acclaimed solo exhibition in the 2003 Venice Biennale; documentation of the video installation Time Left; works from the project In Stone, including stone moving ‘texts;’ and notebook vitrines. Her recent collaboration with the composer Heiner Goebbels, Fields of Fire, which was made following a trip to Kazakhstan, depicts oil-field fires in a landscape that recalls both the fluid ink brush of the Soong and T’ang dynasty and the hyperkinetic pen of the seismograph: the notion of landscape is transformed from the symbol of constancy to an engine of metamorphosis.”

Rovner, Michal

Rovner, Michal: “Michal Rovner: The Space Between

Essays by Sylvia Wolf and Michael Rush.

By repeatedly re-photographing her images, transferring them from video to film and back again, and manipulating them digitally, Michal Rovner creates photographic and video imagery that abstract familiar subjects like houses, animals, and people into ambiguous and iconic forms. Working with representation but against the traditions of narrative and documentary purpose, her artworks imply a tentative universe, one that is paradoxically peaceful and unsettled, vivid and shrouded, and completely counter-factual. If the changing nature of art has resulted in a general blurring of boundaries–between painting and photography, reality and memory, presence and absence–Rovner mines this haziness, refuses to respect borders, and exists completely in The Space Between.”

ΕΛΕΝΗ ΚΕΣΙΣΟΓΛΟΥ: SHIRIN NESHAT

Evi Panteleon,Lucian Freud

Thus spake Freud

“I paint the sort of paintings I can, not the ones I necessarily want.”

“I want paint to work as flesh… my portraits to be of the people, not like them. Not having a look of the sitter, being them … As far as I am concerned the paint is the person. I want it to work for me just as flesh does.”

“I could never put anything into a picture that wasn’t actually there in front of me. That would be a pointless lie, a mere bit of artfulness.”

“The painting is always done very much with [the model’s] co-operation. The problem with painting a nude, of course, is that it deepens the transaction. You can scrap a painting of someone’s face and it imperils the sitter’s self-esteem less than scrapping a painting of the whole naked body.”

“I don’t want any colour to be noticeable… I don’t want it to operate in the modernist sense as colour, something independent… Full, saturated colours have an emotional significance I want to avoid.”

“Since the model he so faithfully copies is not going to be hung up next to the picture … it is of no interest whether it is an accurate copy of the model. Whether it will convince or not, depends entirely on what it is in itself, what is there to be seen. The model should only serve the very private function for the painter of providing the starting point for his excitement. The picture is all he feels about it, all he thinks worth preserving of it, all he invests it with. If all the qualities which a painter took from the model for his picture were really taken, no person could be painted twice.”

“The aura given out by a person or object is as much a part of them as their flesh. The effect that they make in space is as bound up with them as might be their colour or smell … Therefore the painter must be as concerned with the air surrounding his subject as with the subject itself. It is through observation and perception of atmosphere that he can register the feeling that he wishes his painting to give out.”

“A painter must think of everything he sees as being there entirely for his own use and pleasure. … And, since the model he faithfully copies is not going to be hung up next to the picture, since the picture is going to be there on its own, it is of no interest whether it is an accurate copy of the model.”

Lucian Freud, painter

4 Απριλίου 2009

kosmos ideon k synaisthesia

–>

<!– /* Style Definitions */ p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-parent:""; margin:0cm; margin-bottom:.0001pt; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-fareast-font-family:"Times New Roman";} @page Section1 {size:612.0pt 792.0pt; margin:72.0pt 90.0pt 72.0pt 90.0pt; mso-header-margin:36.0pt; mso-footer-margin:36.0pt; mso-paper-source:0;} div.Section1 {page:Section1;}

–> Η φιλοσοφική αναζήτηση, που είχε ξεκινήσει με τους προσωκρατικούς φιλοσόφους, σχετικά με το πώς μπορούμε να γνωρίσουμε τον κόσμο γύρω μας και τις αρχές λειτουργίας του, είχε φτάσει σε αδιέξοδο την εποχή του Πλάτωνα. Οι ηρακλείτειοι υποστήριζαν ότι τα πάντα στον κόσμο του χώρου και του χρόνου συνεχώς μεταβάλλονταν. Ούτε για μια στιγμή δεν σταματούσε η μεταβολή και τίποτα δεν έμενε το ίδιο από τη μια στιγμή στην άλλη. Συνέπεια αυτής της θεωρίας φαινόταν να είναι ότι δεν μπορούμε να γνωρίσουμε αυτόν τον κόσμο, εφόσον δεν μπορεί κανείς να πει ότι γνωρίζει κάτι που είναι διαφορετικό ετούτη τη στιγμή απ’ ό,τι ήταν μια στιγμή πριν. Η γνώση απαιτεί την ύπαρξη ενός σταθερού αντικειμένου. Ο Παρμενίδης, από την άλλη πλευρά, ισχυριζόταν ότι υπάρχει μια σταθερή πραγματικότητα, την οποία μπορούμε να ανακαλύψουμε μόνο μέσω της ενέργειας του νου, χωρίς καμιά ανάμειξη των αισθήσεων. Το αντικείμενο της γνώσης πρέπει να είναι αμετάβλητο και αιώνιο, εκτός χρόνου και μεταβολής, ενώ οι αισθήσεις μας φέρνουν σε ότι είναι μεταβλητο και φθαρτο. Ο Πλάτων θέλοντας να διαφυλάξει το αγαθό της γνώσης και της αντικειμενικής αλήθειας από ιδεολογήματα που την απέρριπταν καταδικάζοντας τον άνθρωπο σε μια άγνοια μόνιμη και οδηγώντας τον τελικά στον αμοραλισμό, υποστήριξε ότι τα αντικείμενα της γνώσης, τα αντικείμενα που θα μπορούσαν να οριστούν, υπήρχαν, αλλά δεν έπρεπε να ταυτιστούν με τίποτε στον αισθητό κόσμο· υπήρχαν σε έναν νοητό κόσμο, πέραν χώρου και χρόνου. Είναι οι περίφημες π λατωνικές ιδέες ή είδη.

«Όλα είναι πολύ΄ρευστά.Πρέπεις να νίωσεις τον ήχο να κινείται.Οι ήχοι είναι ψηλοί,χαμηλοί,γρήγοροι,αργοί…Τα χρώματα μου είναι το ίδιο.Κινούνται με τον ίδιο απόλυτο τρόπο.Είναι ένα πολύ φευγαλέο συναίσθημα και αδύνατο να το προσδιορίσεις με απόλυτο τρόπο.»Το video που εχω κάνει είναι συμβολικό και στηρίζεται στην παραπάνω μαρτυρία ενώς συναισθητικού ατόμου. //www.youtube.com/get_player

Barbara Kruger

Barbara Kruger (born 1945) is an American conceptual artist. She was born in Newark, New Jersey and left there in 1946 to attend Syracuse University. after a year at Syracuse, she moved to New York, where she began attending Parsons School of Design. She studied with Diane Arbus and Marvin Israel, who, as a graphic designer and art director for Harper’s Bazaar in the 1960s, introduced Kruger to photographers and fashion/magazine sub-cultures. after a year at Parsons, Kruger left school and started to work at Mademoiselle magazine as an entry-level designer.

Barbara Kruger (born 1945) is an American conceptual artist. She was born in Newark, New Jersey and left there in 1946 to attend Syracuse University. after a year at Syracuse, she moved to New York, where she began attending Parsons School of Design. She studied with Diane Arbus and Marvin Israel, who, as a graphic designer and art director for Harper’s Bazaar in the 1960s, introduced Kruger to photographers and fashion/magazine sub-cultures. after a year at Parsons, Kruger left school and started to work at Mademoiselle magazine as an entry-level designer.

Much of Kruger’s graphic work consists of black and white photographs with overlaid captions set in white on red Futura Bold Oblique. The phrases included in her work are usually declarative, and make common use of such pronouns as “you”, criticism of sexism ant the circulation of power within cultures is a recurring motif in the work.

Much of Kruger’s graphic work consists of black and white photographs with overlaid captions set in white on red Futura Bold Oblique. The phrases included in her work are usually declarative, and make common use of such pronouns as “you”, criticism of sexism ant the circulation of power within cultures is a recurring motif in the work. For the past decade Kruger has created installations of video, film, audio and projection. Enveloping the viewer with the seductions of direct address, her work is consistently about the kindnesses and brutalities of social life: about how we are to one another.

For the past decade Kruger has created installations of video, film, audio and projection. Enveloping the viewer with the seductions of direct address, her work is consistently about the kindnesses and brutalities of social life: about how we are to one another.

Kruger’s works are direct and evoke an immediate response. usually her style involves the cropping of a magazine or newspaper image enlarged in black and white. The enlargement of the image is down as crudely as possible to monumental proportions. A message is stenciled on the image, usually in white letters against a background of red. The text and image are unrelated in an effort to create anxiety by the audience that plays on the fears of society”. (Janson. p. 992).

Kruger’s works are direct and evoke an immediate response. usually her style involves the cropping of a magazine or newspaper image enlarged in black and white. The enlargement of the image is down as crudely as possible to monumental proportions. A message is stenciled on the image, usually in white letters against a background of red. The text and image are unrelated in an effort to create anxiety by the audience that plays on the fears of society”. (Janson. p. 992). In 2005 Kruger was honored at the 51st Venice Bienalle with the “Golden Lion” for Lifetime Achievement. Kruger is currently a professor at the University of California at Los Angeles.

In 2005 Kruger was honored at the 51st Venice Bienalle with the “Golden Lion” for Lifetime Achievement. Kruger is currently a professor at the University of California at Los Angeles.

In 2007, Kruger was one of the many artists to be a part of South Korea’s Incheon Women Artists’ Bienalle in Seoul. This marked South Korea’s first women’s biennial.

biennial.

Links:

www.barbarakruger.com

en.wikepedia.org/wiki/Barbara_Kruger

3 Απριλίου 2009

ΣΥΝΑΙΣΘΗΣΙΑ είναι η νευρολογική ανάμιξη των αισθήσεων. Ένας άνθρωπος που χαρακτηρίζεται από συναισθησία είναι δυνατό, για παράδειγμα, να “ακούει” τις οσμές, να “βλέπει” τους ήχους και να “μυρίζει” τους ήχους. Το συχνότερο είδος συναισθησίας είναι το να βλέπει κανείς ήχους και το να συνδυάζει αυτόματα αριθμούς με συγκεκριμένα χρώματα. Οι συναισθητικοί συχνά αναφέρουν συσχετίσεις ανάμεσα στις αποχρώσεις των χρωμάτων, τους τόνους των ήχων και στην ένταση των γεύσεων. Για παράδειγμα ένας συναισθητικός είναι πιθανό να “δει” ένα περισσότερο έντονο κόκκινο χρώμα καθώς ανεβαίνει η συχνότητα ενός ήχου ή μία απαλή επιφάνεια μπορεί να έχει “γλυκιά” γεύση. Οι συσχετίσεις αυτές των αισθήσεων για τους συναισθητικούς δεν είναι καθόλου μεταφορικές. Για αυτούς “πραγματικά” τα χρώματα έχουν γεύση, οι οσμές ηχούν κ.λ.π . Η εμπειρία τους αυτή κρατάει σε όλη τη διάρκεια της ζωής τους. Ωστόσο, κάποιες φορές η περίεργη αυτή ιδιαιτερότητα χάνει την έντασή της κατά την ενηλικίωση ή μετά από αυτήν.

Η πιο συνηθισμένη μορφή συναισθησίας είναι η συσχέτιση γράμματος/αριθμού με χρώμα . Το μοτίβο της συσχέτισης διαφέρει από άτομο σε άτομο. Οι ίδιοι οι συναισθητικοί συχνά αγνοούν το ότι οι υπόλοιποι άνθρωποι δεν αντιλαμβάνονται τον κόσμο με τον ίδιο τρόπο.

Colin Miller

Colin Miller has been sculpting since 1966, ten years of which he spent living and working in Greece. He lives and works in Blakeney, North Norfolk, England.

He works in bronze, marble, English stone and varying woods, particularly olive wood. Colin Millers work is both figurative and abstract and is characterised by its sensual and tactile qualities, combined with his use of natural elements and forms. Nature, Greek mythology and the phenomenon of Creation are his principal sources of inspiration. He likes to keep his ideas and themes varied with no limitations. The human figure plays an important part in his work, which moves freely from abstraction to representation.

Dan Graham

Dan Graham (1942, Urbana, Illinois) is a conceptual artist now working out of New York City. He is an influential figure in the field of contemporary art, both a practitioner of conceptual art and an art critic and theorist. His art career began in 1964 when he moved to New York and opened the John Daniels Gallery. Graham’s artistic talents have wide variety. His artistic fields consist of film, video, performance, photography, architectural models, and glass and mirror structure. Graham especially focuses on the relationship between his artwork and the viewer in his pieces. Graham made a name for himself in the 1980’s as an architect of conceptual glass and mirrored pavilions.

Dan Graham (1942, Urbana, Illinois) is a conceptual artist now working out of New York City. He is an influential figure in the field of contemporary art, both a practitioner of conceptual art and an art critic and theorist. His art career began in 1964 when he moved to New York and opened the John Daniels Gallery. Graham’s artistic talents have wide variety. His artistic fields consist of film, video, performance, photography, architectural models, and glass and mirror structure. Graham especially focuses on the relationship between his artwork and the viewer in his pieces. Graham made a name for himself in the 1980’s as an architect of conceptual glass and mirrored pavilions. He is among the most influential of the Conceptual artists who emerged in America during the mid-1960s. A pioneer in performance and video art in the 1970s, Graham later turned his attention to architectural projects designed for social interaction in public spaces, among them The Children’s Pavilion (1989), conceived with Jeff Wall. Since the 1990s Graham has received major public commissions throughout North America and Europe. His writings range from early Conceptual Art pieces inserted in mass-market magazines to texts about his fellow artists.

He is among the most influential of the Conceptual artists who emerged in America during the mid-1960s. A pioneer in performance and video art in the 1970s, Graham later turned his attention to architectural projects designed for social interaction in public spaces, among them The Children’s Pavilion (1989), conceived with Jeff Wall. Since the 1990s Graham has received major public commissions throughout North America and Europe. His writings range from early Conceptual Art pieces inserted in mass-market magazines to texts about his fellow artists.

Dan Graham’s glass-and-metal pavilions–minimalistic structures that deal with perceptual paradox–were the highlights of several recent shows that surveyed the artist’s work.

Dan Graham’s glass-and-metal pavilions–minimalistic structures that deal with perceptual paradox–were the highlights of several recent shows that surveyed the artist’s work.

One of the intriguing and frustrating aspects of Dan Graham’s work is its sheer variety. Over the past 25 years Graham has carried out performances, installations, video works, photographs and, most recently, architectural-scale glass pavilions; in addition, he has published a substantial body of critical and speculative writing.  By attempting to explore Graham’s work in all its complexity, the recent retrospective organized by the Nouveau Musee in Lyons went much further than previous shows (or, for that matter, the traveling exhibition “Dan Graham: Public/Private,” soon to be on view at the Art Gallery of Ontario). In part, this was because the sparsely installed Nouveau Musee exhibition encouraged visitors to discover and trace the connecting threads that run throughout Graham’s production.

By attempting to explore Graham’s work in all its complexity, the recent retrospective organized by the Nouveau Musee in Lyons went much further than previous shows (or, for that matter, the traveling exhibition “Dan Graham: Public/Private,” soon to be on view at the Art Gallery of Ontario). In part, this was because the sparsely installed Nouveau Musee exhibition encouraged visitors to discover and trace the connecting threads that run throughout Graham’s production.

The survey included about 24 works, ranging from Graham’s Conceptual pieces of the mid-’60s to his recent and proposed glass pavilions. While the show focused primarily on these structures–presented via photographs, models and various full-scale constructions–it sought at the same time to avoid the sorts of misunderstandings that arise when Graham’s works are considered as examples of “architecture” or “sculpture.” Graham quite deliberately blurs such boundaries in conceiving, executing and exhibiting his work. For example, in discussing the architectural models which formed the nucleus of the Nouveau Musee show, Graham said:

The survey included about 24 works, ranging from Graham’s Conceptual pieces of the mid-’60s to his recent and proposed glass pavilions. While the show focused primarily on these structures–presented via photographs, models and various full-scale constructions–it sought at the same time to avoid the sorts of misunderstandings that arise when Graham’s works are considered as examples of “architecture” or “sculpture.” Graham quite deliberately blurs such boundaries in conceiving, executing and exhibiting his work. For example, in discussing the architectural models which formed the nucleus of the Nouveau Musee show, Graham said:

My purpose is to use these models as tools of propaganda to generate commissions for similar works, possibly including some (more pragmatic) alterations that adapt the project according to a specific site. I also use such models because of their ambiguity, since it is difficult to clearly define them as “artistic” or architectural works.

This kind of intentional ambivalence about the nature of specific works is characteristic of Graham’s method. The point was underscored in Lyons by presenting some of his models alongside finished, full-scale pavilions. Sometimes these models are “projects” which Graham never really expects to have built, as with Alteration to a Suburban House (1978), which was con

This kind of intentional ambivalence about the nature of specific works is characteristic of Graham’s method. The point was underscored in Lyons by presenting some of his models alongside finished, full-scale pavilions. Sometimes these models are “projects” which Graham never really expects to have built, as with Alteration to a Suburban House (1978), which was con ceived from the start as a theoretical demonstration. But at other times, particularly with the glass pavilions, the models serve as an intermediary design stage. In order to understand how Graham’s work has developed and changed, the visitor must be able to recognize the crucial distinction between the “final” models of the early 1970s and the “provisional” models for pavilions of the ’80s.

ceived from the start as a theoretical demonstration. But at other times, particularly with the glass pavilions, the models serve as an intermediary design stage. In order to understand how Graham’s work has developed and changed, the visitor must be able to recognize the crucial distinction between the “final” models of the early 1970s and the “provisional” models for pavilions of the ’80s.

For instance, there were three small-scale models of his recent Gift Shop/Coffee Shop (1989) in the show, each representing a different version of the project, as well as a completed pavilion. By siting the full-scale work within the museum’s neutral, indoor exhibition space, Graham and the curators forced visitors to puzzle over how to approach it: as a sculpture within an exhibition or, in the artist’s words, “as something real and permanent–in short an architectural Work.”

Graham’s earliest work grew out of the New York art milieu of the mid-1960s. In 1964 he and a friend opened a Manhattan gallery dedicated to avant-garde art. The gallery lasted only a year, but it brought Graham in contact with figures like Robert Smithson, Jo Baer, Dan Flavin and Donald Judd. Not long after, Graham began to formulate his own art projects, which reflected concerns shared by his Minimalist and Conceptualist peers: the notion of the art work as a “structure of information” rather than a physical object, the nature of the spectator’s perceptual experience within the gallery space, and the effect (both aesthetic and economic) of the reproduction of art works in magazines.

For example, Graham investigated the effects of art’s “technical reproduction” by making Conceptual pieces meant to exist solely as texts appearing in the advertising or editorial sections of various magazines. Works such as Schema, Figurative and Homes for America (all 1966) were published in both avant-garde journals and general circulation magazines, ranging from Art and Language to Arts Magazine to Harper’s Bazaar. Schema, which resembles a Minimalist poem, is simply a list of the technical specifics of its own presentation: the number of words and letters printed, the name of the paper stock and type-face used, the

For example, Graham investigated the effects of art’s “technical reproduction” by making Conceptual pieces meant to exist solely as texts appearing in the advertising or editorial sections of various magazines. Works such as Schema, Figurative and Homes for America (all 1966) were published in both avant-garde journals and general circulation magazines, ranging from Art and Language to Arts Magazine to Harper’s Bazaar. Schema, which resembles a Minimalist poem, is simply a list of the technical specifics of its own presentation: the number of words and letters printed, the name of the paper stock and type-face used, the  paper size and so on. Since the particulars change with each publication in different journals, Schema exists both as a purely conceptual “data field” and as a series of varying physical incarnations. Homes for America, a photo-and-text essay on the permutations of colors and architectural styles of suburban tract houses, was published in Arts Magazine in 1967. But the piece might also be regarded as an unpredictable mix of Conceptual art and cultural criticism, in which postwar housing developments are treated as examples of “serial logic” and minimalist form.

paper size and so on. Since the particulars change with each publication in different journals, Schema exists both as a purely conceptual “data field” and as a series of varying physical incarnations. Homes for America, a photo-and-text essay on the permutations of colors and architectural styles of suburban tract houses, was published in Arts Magazine in 1967. But the piece might also be regarded as an unpredictable mix of Conceptual art and cultural criticism, in which postwar housing developments are treated as examples of “serial logic” and minimalist form.

Links

2 Απριλίου 2009

ΕΡΕΥΝΑ ΓΙΑ ΤΗΝ ΣΥΝΑΙΣΘΗΣΙΑ

ΣΥΝΑΙΣΘΗΣΙΑ

Ως συναισθησία (εκ του συν και του αίσθησις) ονομάζουμε τη μη φυσιολογική (με την έννοια ότι εμφανίζεται σπάνια) νευρολογική κατάσταση κατά την οποία ένας κατά τα άλλα υγιής άνθρωπος βιώνει δύο ή και περισσότερες αισθήσεις ταυτόχρονα. Ένα ερέθισμα το οποίο εγείρει μια συγκεκριμένη αίσθηση, ακούσια εγείρει και μια επιπλέον αίσθηση. Η συναισθησία σαφώς διακρίνεται από την καλλιτεχνική μεταφορά, τον συμβολισμό και κάθε άλλου τύπου “καλλιτεχνικές” συσχετίσεις. Η συναισθησία φαίνεται να συσχετίζεται με το αριστερό ημισφαίριο του εγκεφάλου. Με απλά λόγια, αν “βλέπετε” τις πρώτες συγχορδίες από την Παθητική του Μπετόβεν, ή βρίσκετε λίγο “αλμυρό” το ορθογώνιο τρίγωνο που σχεδιάσατε για να αποδείξετε το Πυθαγόρειο Θεώρημα, τότε μάλλον είστε συναισθητικός (πολύ πιο ενδιαφέρον από το να είστε συναισθηματικός).

Από το 1880 οι επιστήμονες γνωρίζουν για το φαινόμενο της συναισθησίας. Ο Francis Galton, ξάδελφος του Δαρβίνου, έγραψε ένα άρθρο σχετικά με το φαινόμενο στο περιοδικό Nature το 1883. Γρήγορα το επιστημονικό ενδιαφέρον για την συναισθησία αμβλύνθηκε (εν πολλοίς οφείλεται στο μπιχεβιορισμό). Θεωρήθηκαν τότε απατεώνες όσοι ισχυρίζονταν ότι ήταν συναισθητικοί, ή ακόμη χειρότερα, χρήστες ψυχοτρόπων ουσιών ( το LSD, το χασίς και η μεσκαλίνη δημιουργούν ανάλογα φαινόμενα). Η αλήθεια είναι ότι πολλοί συνθέτες ιδίως του τέλους του 19ου αιώνα έπαιρναν παραισθησιογόνα για να βιώσουν συναισθητικές εμπειρίες. Η επιληψία του επιχείλιου λοβού, διάφορες κακώσεις του εγκεφάλου, η προσωρινή απώλεια των αισθήσεων καθώς και η ηλεκτρική διέγερση του εγκεφάλου είναι γνωστό ότι προκαλούν φαινόμενα ανάλογα της συναισθησίας. Πάντως από το 1980 και μετά το ενδιαφέρον για την συναισθησία αναζωπυρώθηκε και διενεργούνται αρκετά επιστημονικά πειράματα για τη μελέτη του φαινομένου.

Οι συναισθητικοί μπορεί να είναι δύο κατηγοριών: προσεταιριστικοί (associators) και προβολικοί (projectors) [2]. Δεν αποκλείεται ένας συναισθητικός να ανήκει και στις δύο κατηγορίες. Εξηγώ με παραδείγματα: ο προσεταιριστικός ακούει τη νότα Ντο και “αισθάνεται” το κόκκινο χρώμα, δεν το “βλέπει” πραγματικά, το ‘σκέφτεται”, “ξέρει” ότι το Ντο είναι κόκκινο (Ο Messiaen πρέπει να ήταν αυτής της κατηγορίας συναισθητικός). Ο προβολικός ακούει τη νότα Ντο και προβάλλει ακούσια το κόκκινο χρώμα πάνω στη νότα έτσι ώστε πραγματικά να “βλέπει” το Ντο σαν κόκκινο. Καταλαβαίνετε ότι η συναισθησία δεν μπορεί να περιγραφεί με λέξεις, ιδιαίτερα από έναν μη συναισθητικό.

Μπορούμε να διακρίνουμε τις κατωτέρω μορφές συναισθησίας:

1. Μουσική – Χρωματική συναισθησία

Αντιστοίχιση των τονικών υψών (π.χ. ντο, ρε, …), των συγχορδιών (π.χ. Ντο μείζονα, Φα ελάσσονα, …), των τονικοτήτων (π.χ. τονικότητα της Σολ μείζονος), των οργανικών ηχοχρωμάτων (ήχος βιολιού, τρομπέτας, κλπ) με συγκεκριμένα χρώματα, ή μίξεις χρωμάτων αν πρόκειται για συγχορδίες. Δεν βλέπουν όλοι οι μουσικά – χρωματικά συναισθητικοί τα ίδια χρώματα (π.χ. το χρώμα του Ντο του Messiaen διαφέρει από αυτό του Scriabin). Οι μουσικά – χρωματικά συναισθητικοί έχουν σχεδόν πάντα απόλυτο αυτί. ‘Ίσως η πιο κοινή μορφή συναισθησίας.

2. Γραφική – Χρωματική συναισθησία

Αντιστοίχηση των γραμμάτων του αλφαβήτου και των αριθμών με συγκεκραμένα χρώματα. Δεν βλέπουν όλοι οι συναισθητικοί τα ίδια χρώματα.

3. Συναισθησία Αριθμητικής Μορφής

Οι συναισθητικοί αυτής της μορφής αντιλαμβάνονται τους αριθμούς σε ορισμένες θέσεις, όπως οι πόλεις για παράδειγμα σε ένα χάρτη, ή οι θέσεις των αριθμών σε ένα ρολόι. Οι συναισθητικοί αριθμητικής μορφής συνήθως απομνημονεύουν μεγάλους αριθμούς χρησιμοποιώντας αυτήν τους την ικανότητα (π.χ. απομνημόνευση μεγάλου μέρους ψηφίων του δεκαδικού αναπτύγματος του π).

4. Προσωποποιία

Οι συναισθητικοί αυτής της μορφής αποδίδουν στα τακτικά αριθμητικά, τις μέρες της εβδομάδας, τους μήνες του χρόνου κλπ, ανθρώπινους χαρακτήρες, προσωπικότητες. Για παράδειγμα το “1” μπορεί να το θεωρεί ένας συναισθητικός “γαλήνιο” και “αυτάρκες”, το “7” “δυνατό” αλλά “δύστροπο” (το ότι θεωρούμε την Κυριακή την καλλίτερη μέρα της εβδομάδος δεν μας καθιστά συναισθητικούς).

5. Λεξική / Σχηματική – Γευστική συναισθησία

Λέξεις ή φωνήματα μιας γλώσσας, καθώς και διάφορα σχήματα δημιουργούν το αίσθημα της γεύσης. Σχετικά σπάνια μορφή συναισθησίας.

Λίγη στατιστική: 1/25000 είναι συναισθητικός (Cytowic, 1995). 3/1 υπερτερούν οι γυναίκες με διαγνωσμένη κάποια μορφή συναισθησίας στις ΗΠΑ. 6/7 συναισθητικούς είναι αριστερόχειρες. Η μουσική – χρωματική συναισθησία εμφανίζεται συχνότερα σε καλλιτέχνες και δη μουσικούς (Domino, 1989).

6.Η Συναισθησία στην τέχνη

Η έννοια της συναισθησίας συναντάται αρκετά συχνά στην τέχνη τόσο από καλλιτέχνες που ήταν συναισθητικοί όσο και από καλλιτέχνες που δεν είχαν αυτή την ιδιότητα. Το φαινόμενο της συναισθησίας απασχόλησε και το θεατρικό σκηνοθέτη Πίτερ Μπρουκ χωρίς ο ίδιος να είναι πάσχων. Μεταξύ άλλων, συναντάται στην ποίηση του Αρτούρ Ρεμπώ και του Σαρλ Μποντλέρ, στη ζωγραφική του Βασίλι Καντίνσκι, σε μυθιστορήματα του Βλαντιμίρ Ναμπόκοφ και στη μουσική των Αλεξάντερ Σκριάμπιν και Ολιβιέ Μεσιάν.

Επιστρέφουμε στον Messiaen. Μερικά παραδείγματα της χρωματικής συναισθησίας του:

• Ο Τρόπος 2 [3] εγείρει το χρωματικό αίσθημα αποχρώσεων του βιολετί, του μπλε και του πορφυρού χρώματος.

• Ο Τρόπος 3, πορτοκαλί μαζί με κόκκινο και πράσινο και χρυσαφί κηλίδες, επίσης ένα γαλακτώδες λευκό με αντανακλάσεις ιριδίζοντος οπαλίου.

• Πολλά παραδείγματα βρίσκουμε στο Catalogue d’ Oiseaux. Για παράδειγμα συγχορδίες συσχετίζονται με τα χρώματα της ανατολής και της δύσης του ήλιου.

• Στα έργα του Sept Haïkaï και Couleurs de la Cité céleste καταγράφει τα χρώματα συγκεκριμένων συγχορδιών πάνω στην παρτιτούρα.

Ερευνητές από το Ισραήλ, την Αγγλία και την Ισπανία συνεργάστηκαν σε ένα πρόγραμμα, το οποίο έδειξε πως οι άνθρωποι με μέσο δείκτη ευφυΐας μπορούν να έχουν συναισθητικές εμπειρίες, μπορούν δηλαδή να διεγείρουν μία από τις αισθήσεις που προκαλεί την ακούσια χρήση της άλλη.

Παραδείγματα αυτού του φαινομένου είναι όταν κάποιος βλέπει ένα συγκεκριμένο αριθμητικό ψηφίο ως ένα συγκεκριμένο χρώμα ή όταν το άκουσμα ενός συγκεκριμένου ήχου φέρνει στο νου την εμπειρίας μίας συγκεκριμένης γεύσης.

Τα ευρήματα της έρευνας, τα οποία δημοσιεύτηκαν στο επιστημονικό περιοδικό Psychological Science, έρχονται σε αντίθεση με τη μέχρι σήμερα αντίληψη ότι η συναισθησία εμφανίζεται μόνο σε άτομα που έχουν παραπάνω συναπτικές συνδέσεις στον εγκέφαλο.

Με τη χρήση μίας τεχνικής, που ονομάζεται μετά-υπνωτική υποβολή, οι ερευνητές απέδειξαν πως είναι δυνατόν να προκαλέσεις σε έναν άνθρωπο συναισθητικές εμπειρίες.

Σε μία δοκιμή, που έγινε για να επιβεβαιωθεί ότι οι συμμετέχοντες βίωσαν πραγματικά μία συναισθητική εμπειρία, οι ερευνητές ρώτησαν όσους είχαν υπνωτιστεί με σκοπό να δουν τον αριθμό «7» ως κόκκινο, εάν μπορούσαν να δουν τον αριθμό όταν αυτός ήταν τυπωμένος με μαύρο χρώμα πάνω σε ένα κόκκινο φόντο. Εάν οι συμμετέχοντες δεν μπορούσαν να δουν το ψηφίο, οι ερευνητές συμπέραιναν πως η προκαλούμενη από υπνωτισμό συναισθησία ήταν γεγονός.

Η έρευνα δείχνει πως οι «παρεμβολές» μέσα στον εγκέφαλο μπορεί να είναι η αιτία των συναισθητικών εμπειριών και όχι οι επιπλέον εγκεφαλικές συνδέσεις. Ο Cohen Kadosh, που συμμετείχε στην έρευνα είπε χαρακτηριστικά: «Η δοκιμή αυτή μας πάει ένα βήμα πιο κοντά στην κατανόηση των αιτιών της συναισθησίας και των αφύσικων παρεμβαλλόμενων στον εγκέφαλο αλληλεπιδράσεων.»

πηγή : pathfinder.gr

Όταν ένα άτομο μπορεί να δει έναν ήχο και να ακούσει μία εικόνα τότε είναι σίγουρο ότι πάσχει από μία πάρα πολύ σπάνια και περίεργη νόσο που ονομάζεται συναισθησία.

ΧΑΡΑΚΤΗΡΙΣΤΙΚΑ ΤΗΣ ΝΟΣΟΥ:

Είναι πολύ σπάνια.-1/25.000 άτομα. Τα περισσότερα άτομα με συναισθησία είναι θηλυκού γένους. Το ίδιο ισχύει για τους αριστερόχειρους. Ποτέ δεν παρατηρήθηκε ο πατέρας με συναισθησία να αποκτά γιο με συναισθησία. Νευρολογικά τα άτομα είναι υγιή. Πλέον οι ερευνητές αναζητούν στο Χ χρωμόσωμα το γονίδιο της συναισθησίας…

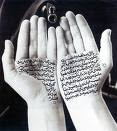

Εικόνα 3.2.15β : Πρόκειται για μία μορφή απεικόνισης του πώς αντιλαμβάνεται ένας άνθρωπος με συναισθησία την ακοή…

ΤΙ ΚΑΝΕΙ ΤΟΥΣ ΕΡΕΥΝΗΤΕΣ ΝΑ ΣΥΣΧΕΤΙΖΟΥΝ ΤΗΝ ΝΟΣΟ ΜΕ ΤΗΝ ΑΔΡΑΝΟΠΟΙΗΣΗ ΤΟΥ Χ ΧΡΩΜΟΣΩΜΑΤΟΣ:

Ο Cytowic (1995) και οι Simon-Cohen(1996) πραγματοποίησαν εκτεταμένες έρευνες και κατηγοριοποίησαν τους ανθρώπους που έπασχαν από συναισθησία. Έτσι βρήκαν ενδιαφέροντα δημογραφικά αποτελέσματα Το πρώτο χωρίς ενδοιασμούς ήταν ότι η συναισθησία είναι μια πάρα πολύ σπάνια νόσος. Σύμφωνα με τις έρευνες των Η.Π.Α. του Cytowic αποδείχτηκε ότι η συναισθησία παρατηρείται σε 1 στους 25000 ανθρώπους. Ταυτόχρονα, στο Ηνωμένο Βασίλειο της Αγγλίας, οι μελέτες των Baron-Cohen απέδειξαν ένα μεγαλύτερο ποσοστό της τάξεως του 1 στα 2000 άτομα. Και οι δύο έρευνες απέδειξαν ότι οι περισσότεροι ασθενείς είναι γένους θηλυκού. Ο Cytowic βρήκε μια συχνότητα 3:1, ενώ οι Baron-Cohen 6:1.Επίσης, οι ασθενείς με συναισθησία είναι κυρίως αριστερόχειρες.

Ενδιαφέρον είναι το γεγονός ότι η συναισθησία εμφανίζεται να υπάρχει σε οικογένειες και δεν έχει εμφανιστεί ποτέ περίπτωση πατέρας με συναισθησία να κληρονομεί την νόσο και στον γιο του. Αυτό οδηγεί σε υποψίες τους ερευνητές ότι δηλαδή η συναισθησία είναι μία από τις ασθένειες που σχετίζονται με την αδρανοποίηση του Χ χρωμοσώματος. Επιπλέον, πολλοί άνθρωποι με συναισθησία φαίνεται να είναι υγιείς και τα καταφέρνουν πολύ καλά στις νευρολογικές εξετάσεις. Έχουν καλά αποτελέσματα στα τεστ νοημοσύνης αλλά παρουσιάζουν δυσκολίες στα Μαθηματικά.

Σε ένα πολύ ενδιαφέρον πείραμα των Stevenson, Bakes, Prescott βρέθηκε ότι μπορούσαν να αναπτύξουν μια συναισθησία μυρωδιάς-γεύσης με βάση τη μάθηση ( Stevenson 1998). Αναμειγνύοντας ένα μυρωδικό λουλουδιού με ζάχαρη και μετά βάζοντας τους δοκιμαστές να δοκιμάσουν το μείγμα, οι ερευνητές διαπίστωσαν ότι μπορούσαν να μυρίσουν τη γεύση της ζάχαρης. Αυτό είναι ξεκάθαρο, ισχυρίστηκαν, και τούτο γιατί η μύτη δεν έχει υποδοχείς για τη γεύση τόσους όσους έχει το στόμα. Παρόλα αυτά το πείραμα της γεύσης του αρώματος του λουλουδιού είναι απόδειξη του φαινομένου της συναισθησίας μυρωδιάς-γεύσης. Αυτό το πείραμα απέδειξε ότι η συναισθησία είναι κάτι που μαθαίνεται.

Το φαινόμενο βρίσκεται υπό εξέταση…

Άρθρα και ιστοσελίδες που συμβουλεύτηκα

• Scientific American

• Emerson, Lisa J. Mixed Signals

• Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Synesthesia

• Ball, Malcom. The Olivier Messiaen Page

• Easton, Judith A. A Review of Synesthesia: Colored Hearing, Creativity and Research

• Cytowic, Richard. Synesthesia: Phenomenology And Neuropsychology

Βιβλιογραφία περί της Συναισθησίας

• Baron-Cohen, S., Wyke, M., & Binnie, C., (1987). Hearing words and seeing colours: An experimental investigation of a case of synesthesia. Perception, 16, 761-767.

• Bernard, J. (1986). Messaien’s synesthesia: The correspondence between color and sound structure in his music. Music Perception, 4, 41-68.

• Cytowic, R. (1995). Synesthesia: Phenomenology and neuropsychology. Psyche, 2, 2-10.

• Domino, G. (1989). Synesthesia and creativity in fine arts students: An empirical look. Creativity Research Journal, 2, 17-29.

• Hubbard, T. (1996). Synesthesia-like mappings of lightness, pitch, and melodic interval. American Journal of Psychology, 109, 219-239.

• Peacock, K. (1985). Synesthetic perception: Alexander Scriabin’s color hearing. Music Perception, 2, 483-506.

• Paulesu, E., Harrison, J., Baron-Cohen, S., Watson, J., Goldstein, L., Heather, J., Frackowiak, J., & Frith, C. (1995). The physiology of coloured hearing: A PET activation study of colour-word synesthesia. Brain, 118, 661-676.

• Rizzo, M., & Eslinger, P. (1989). Colored hearing synesthesia: An investigation of neural factors. Neurology, 39, 781-784.

• Van Campen, C. (1997). Synesthesia and artistic experimentation. Psyche, 3, 1-7.

• Van Campen, C. (1999). Artistic and psychological experiments with synesthesia. Leonardo, 32, 9-14.

ΠΛΗΡΟΦΟΡΙΕΣ ΑΠΟ ΤΗΝ ΒΙΚΙΠΑΙΔΕΙΑ ,ΤΟ BLOG ΤΟΥ

ΓΕΡΑΣΙΜΟΥ ΜΠΕΡΕΚΕΤΗ ΚΑΙ ΔΙΑΦΟΡΕΣ ΑΛΛΕΣ ΙΣΤΟΣΕΛΙΔΕΣ

(ΑΝΑΣΤΑΣΙΑ ΑΡΓΥΡΟΠΟΥΛΟΥ)